Food in the Pantry

UNM archaeologist and Prof. Keith Prufer co-led a team excavating a site in Belize...

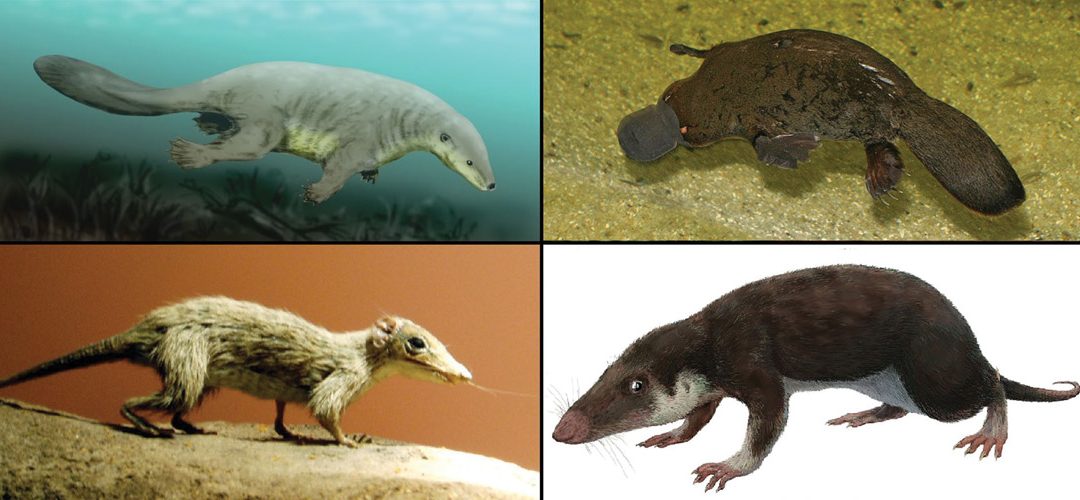

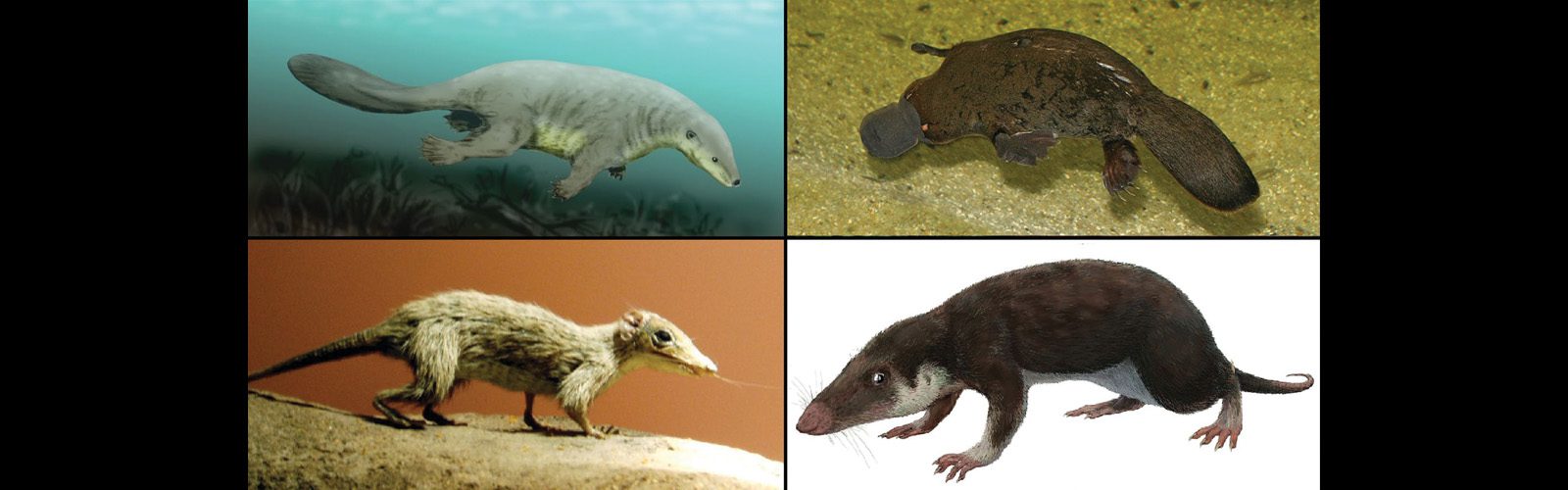

Mammals have the largest brains in relation to body size among vertebrates, but which came first? New research that examined the assumption that enlarging brains led to larger body sizes in mammalian evolution found instead that body size was the first to increase, followed by bigger brains.

UNM Biology Prof. Felisa Smith, an expert on body size evolution and president-elect of the American Society of Mammalogists, was asked by the prestigious journal Science to interpret the new findings, which looked at the explosion of mammalian diversification after dinosaurs went extinct.

“But did brain size also increase proportionately? The study, it turns out, showed that it didn’t,” Smith said. “Essentially mammals got bigger and ‘dumber’ first. Once these body size niches were all full, then there was strong selection on brain size and mammal brain size increased.”

Why?

“Brains are energetically expensive, which means that if you had two animals of the same size, the one with the larger brain would require much more energy (food) to survive. Because energy is often limiting for animals, this means that other activities, and especially reproduction, are scaled down. Indeed, animals with relatively larger brains for their bodies have lower reproductive rates,” Smith said.

UNM archaeologist and Prof. Keith Prufer co-led a team excavating a site in Belize...

UNM grad helps spark electric vehicle revolution…

Read MoreOpera singer pivots to performance coaching…

Read MoreAlumnus caps computing career with prestigious prize…

Read MoreAlumna heads up museum devoted to the American Indian experience…

Read MoreAlumni board president keeps UNM ties tight…

Read MoreAlumni take home a Grammy and a Pulitzer for music…

Read More

When we describe the Alumni Association, we think of words like network, connection, sharing, support, enrichment and discovery. These words capture what we’re trying to accomplish with you and for you at the UNM Alumni Association. When you graduated as a Lobo, you became a Lobo for Life — an automatic member of our alumni association. And now we want to ensure you have the opportunities you want, whether it’s simply to be informed or to be actively engaged.

For those wanting to keep updated on the programs and work of the Association, there are two best places. One is The Howler, which is emailed to you on the first Thursday of each month. The second is our website, with up-to-date information on events, activities and opportunities to engage.

And of course, we know every Lobo looks forward to the Mirage magazine filled with interesting stories about our alums around the country. Our alums are doing amazing things in their jobs and communities. The interesting developments since their graduation are fascinating to discover and bring to you.

And now our biggest focus for this year is to get you involved in what we’re doing. We want you to participate, whether it’s attending an event — in person or virtually — or it’s joining a regional or affiliate chapter, a committee, or considering nominating yourself for a board member position. You could take advantage of our Lobo Career Network, which provides support to alums at every stage of their career. We’re also putting together the Alumni Business Directory to acknowledge and promote our alum-owned businesses. These opportunities and more are outlined on our website or you can reach out to us to find out more.

An here’s a reminder of an easy way to help the Alumni Association: When it comes time to renew your vehicle registration, order a UNM prestige plate. It’s a great way to support your alumni association activities.

I’d like to conclude with a special congratulations to our Alumni Emeriti. We enjoyed hosting the classes of ’70, ’71 and ’72 this past May at Hodgin Hall for a reception, breakfast with President Stokes, a tour of campus and concluding with the Commencement ceremony and special recognition of our alums. See our photo section for more.

To all of you Lobo for Lifers, we appreciate your support and engagement with UNM and the UNM Alumni Association. Go Lobos!

Connie Beimer

Vice President for Alumni Relations, UNM

Executive Director, UNM Alumni Association

With the arrival of autumn comes the smell of roasting chile, the sight of hot air balloons on the horizon...

Photo: Walter Lamar

by Mirage Staff

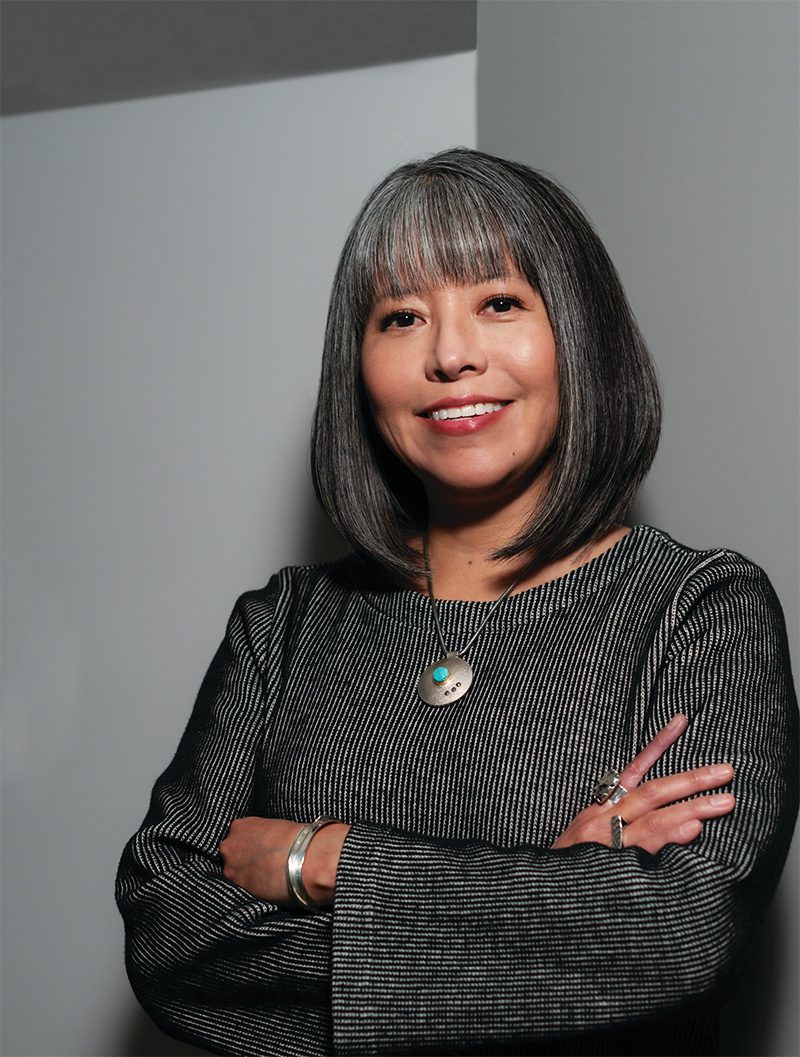

Cynthia Chavez Lamar (’01 PhD), the new director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, was born in Dallas, where her family was living under the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Voluntary Relocation Program. While her father trained as an architectural draftsman, the young family missed home — San Felipe Pueblo along the Rio Grande in New Mexico. The Chavez family — father Richard of San Felipe, mother Sharon who is Hopi, Navajo and Tewa, and three children — put their roots back down in San Felipe, where Cynthia excelled in school, graduated as valedictorian of Bernalillo High School and went on to study art at Colorado College.

Her grounding in Pueblo culture and tradition help to guide her in her new role as the first Native American woman to lead the National Museum of the American Indian’s museum system. And she credits her PhD in American Studies from UNM in 2001 with helping her to learn the importance of collaboration with tribes in curating museum exhibitions.

Mirage talked to Chavez Lamar about the National Museum of the American Indian, her time at UNM and best practices for getting New Mexico chile and salsa back to D.C. in her luggage. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Cynthia Chavez Lamar

Mirage: Tell me about your childhood.

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: I grew up in San Felipe and went to school there too, so it was really an important part of my upbringing, being in the community and being part of the community. That really forms a strong basis for my identity. My dad made heishi (beads) and is also a self-taught jeweler. He has become a master of lapidary work. Both of my parents stressed education a lot and my mom, since we were very little, used to read to us every night. We grew up with a love of reading. I was a good student. I knew that it was important to my family and to my future that I do my best in school. So I tried really hard and did well.

Mirage: Then you went to Colorado College and majored in studio art. How did you find CC?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: That’s a funny story. My dad being a jeweler, he participated in these exclusive small tours in the summers to see artists at home. So they would come to our house and my mom would have a great lunch for them and they would get to talk to my dad about his jewelry. In this one group there was a Dartmouth recruiter and he started talking to me about Dartmouth and was encouraging me to apply to Dartmouth. And I told him, “That’s too far from New Mexico; I really want to be closer to home.” And he said, “Well, I know this great small liberal arts college in Colorado called Colorado College. You might want to check it out.” I always tell people at Colorado College I was recruited to CC by a Dartmouth recruiter.

Mirage: And you majored in studio art?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: Growing up around art and artists, it was a big part of my life and upbringing. My mom from her Hopi/Tewa side knew how to do traditional clay pottery, so she taught us to work with clay. I would make all kinds of different figures. When I went to college it just seemed like something that was just part of me and it seemed natural to go that route. At CC I did printmaking and photography. I enjoyed it, but I’ve always been a practical person, so I knew by my junior year that I wasn’t strong enough in any of those and I knew that if I was going to pursue the path of being an artist it certainly would be a struggle and it would take a long time. And I thought, “I’m really going to need a paying job,” so I decided to go to grad school. I had to think about, “What is it I’m interested in? I’m definitely interested in American Indian subject matter because of my background, because of who I am.” At the time there were only two master’s programs in American Indian studies, and I decided

to go to UCLA.

Mirage: What was your path into museum work?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: When I was at UCLA I had the opportunity to work with a guest curator who was doing a show on Hopi kachina dolls for the UCLA Fowler Museum. That experience involved some fieldwork — a lot of research — and introduced me to the curatorial process and I really liked that. It allowed me to still be involved with Native art, it allowed me to use my intellect, it allowed me to explore new subjects. To me, it was a creative process in its own way. That’s when the bug bit me. And I thought I needed to get my PhD if I want to be a curator, so that’s why I ended up at UNM.

With her parents Richard and Sharon Chavez in 2004 during the grand opening of the National Museum of the American Indian.

Mirage: Was that about coming home? The strength of the program?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: UNM had the only PhD program where you could specialize in Native American art history. And it also was about coming home. I had a bit of a hiccup on my master’s thesis because once my dad found out the topic I was working on, he said, “You can’t do that.” It was a cultural issue. When I was at UCLA, I started looking at issues around representation, especially when it comes to American Indian culture. Throughout history, sacred and ceremonial items have often been on display in museum exhibitions. I was looking carefully at that history and that was what my master’s thesis was going to be about. My dad’s concern was that at our pueblo, given your position in the community, there are only certain things that you should know or you should acknowledge you know. If you’re a woman, like me, and you’re not initiated into any societies or groups and don’t live in the community, you’re probably a person who is considered to have very little knowledge of certain things.

By looking at the display of sacred and ceremonial items in exhibitions, I think he was concerned that I would start getting into the details of what those things were, and as a Pueblo person you always have to be mindful that what you do outside your community can impact your family. That really put me into personal turmoil, because I questioned who I was as a San Felipe Pueblo person. I thought, “Have I really forgotten who I am?” It was kind of traumatic, honestly. But professionally it made me think about how can I still address this as an issue, because it is an issue. We need to let museums and non-Native people know that to have sacred and ceremonial items on display is problematic. With my PhD I looked at the history of anthropology and how in the past anthropologists were always digging and trying to get information out of Pueblo people about secret or sacred information and what that resulted in. That was my way to address something that I thought was important to address but stay true to who I am as a Pueblo person.

Mirage: At UNM were there any particular mentors?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: The person that had the most impact on me was Dr. Mari Lyn Salvador, who is no longer with us. She was in the Anthropology Department and her scholarly practice was one that centered on collaboration. That’s really when I got introduced to the idea that in curating an exhibition, you can collaborate with artists and with Indigenous community members.

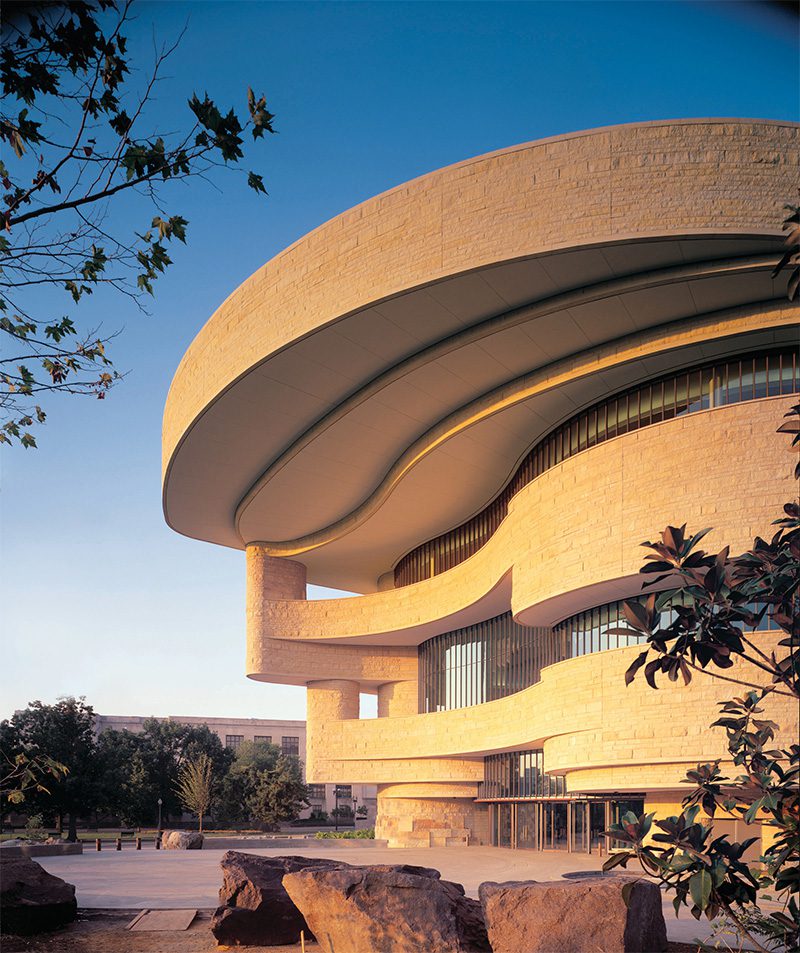

Mirage: That brings me to the question of your museum now and importance of collaboration with the communities who you are putting on display. Your museum feels different from other museums. Can you explain that?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: The museum’s origins were really based on collaboration and advocacy from Native Indigenous peoples. A lot of collaboration was done with Indigenous people to establish exhibitions, to develop the architectural concepts of the museum on the Mall and the Cultural Resources Center in Suitland, Md. The museum’s origins are based on Native Indigenous values and beliefs and concepts. That’s like our foundation that sustains us. That spirit is there and it will never go away, because that’s how NMAI was born.

Mirage: It’s a big responsibility. How are you feeling about the job?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: It’s definitely a lot of responsibility, but it’s also something I know I don’t have to do alone. Thankfully there’s a tremendous staff in place and they’re the ones that make the museum operate on a day-to-day basis. So I have a tremendous amount of gratitude for them and the work that they do. I think it’s going to take me about a year to sort of settle and to feel like I have both feet on the ground. I’m still in the stage of learning something new every day. We’re strong now. But I think my challenge is trying to find that time to think about some bigger initiatives that the museum needs to take on to become even stronger.

Mirage: When you have challenges, what is your support system?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: For me, family is really important. I have a great husband, (former BIA law enforcement deputy director) Walter Lamar. He’s a tremendous person in Indian Country. And thankfully I still have both my parents. They’re always there for me. And my brother and my sister are also there for me. I do rely on family to help me get through challenging times.

Mirage: How often do you get back to New Mexico?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: Before the pandemic I’d get back four to six times a year — work and personal visits. I’m hoping as travel is opening up and I’m getting more comfortable traveling again that I’ll be able to get back to New Mexico at least that much again. I was actually just there for our May 1 feast day. We had it after two years of not having it. We were all very excited but also a little bit nervous. It went well and it wasn’t crazy busy, so I actually had time to sit for a bit and watch the dances. One of the things that I’ve really missed over the course of the pandemic was hearing the songs and seeing the dances. You don’t realize how much you miss something until it’s not there. That was really comforting to me and much needed.

Mirage: What food is the Chavez home famous for on feast days?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: There’s two things that people always ask us to make and it’s spinach casserole, which is interesting, and cheesecake.

Mirage: How do you get New Mexico food in D.C.?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: I get things through the mail sometimes. My mom overnights me some things. And when I go home, I usually pack my suitcase. Now at the Albuquerque airport they sell the frozen red and green Bueno post-security, so I’ll sometimes bring a small cooler with me and fill it up and bring it home. I had lunch with Deb Haaland (U.S. Secretary of the Interior and fellow UNM alumna) about a month ago and I wanted to bring her something so my gift to her was a jar of Sadie’s Not As Hot salsa.

The National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Last fall, we changed software systems for gathering information which includes the listings for alums who have died this past year. If the name of a loved one who died between January 1 and June 31, 2022 is not included in these pages, please accept our condolences and know we want to honor your family member or friend in our alumni magazine. Please let us know their name via email at alumni@unm.edu. We will include the name in the In Memoriam section of our Spring 2023 print issue.

Singer, Jerre J. ’41

DeHerrera, Lena C. ’45

Ullom, Beryl ’46

Goode Jr., Nathan E. ’48

Riley, Brent Locke ’48

Silver, Leon Theodore ’48

Galloway, Lewis Dayton ’49

Gentry, Mary Severns ’49 ’51

Gordon, Larry J. ’49 ’51

Hofheins, Mareth C. ’49

Lareau, Richard J. ’49

Warren Jr., Harold J. ’49

News, notes and updates from UNM Alumni...

Taking a novel approach to understanding climate change, Paul Hooper, adjunct associate professor of Anthropology, dived into existing data sets that contain historical information about societies, including measures of complexity in language, government and economies. He reanalyzed that information to look at how societies fared during cooling periods.

“I found that societies were substantially less complex during the coldest centuries of these climate events. For societies in northern regions, cooling was associated with a loss of about 300 years of accumulated social complexity,” Hooper said. “The research shows that the success of civilizations depends on favorable climatic conditions.”

While Hooper focuses on cooling, not warming, his analysis published in Cliodynamics: The Journal of Quantitative History and Cultural Evolution illuminates yet another potential disruption of changing climate.

“Societies based on agriculture, like our own, are productive within a surprisingly narrow range of climatic conditions,” Hooper said. “Too cold, too hot, or too little water, and productivity suffers. Complex societies have never faced the climate conditions that are now on the horizon, and they’re going to be a shock to our social and economic systems. In addition to higher temperature, precipitation will also be key. While some areas will dry up, others will receive more water due to higher rates of evaporation from the oceans.”

UNM archaeologist and Prof. Keith Prufer co-led a team excavating a site in Belize...

Recent Comments