Big League

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

Read More

Rachel Balkovec (’09 BS) makes baseball history

Photos: Courtesy of New York Yankees

Former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder

By Leslie Linthicum

On Jan. 10, former New York Yankees All-Star pitcher CC Sabathia tweeted a photo of UNM alumna Rachel Balkovec fitted out in Yankees pinstripes with the message: “Keep breaking barriers, Rachel. Salute!”

It was a big day for Balkovec (’09 BS), a history-making day in a sports career that has seen its share of firsts.

At 28, Balkovec was the first woman to be named a conditioning coach for a Major League Baseball team when she took over as the Latin America strength and conditioning coordinator for the Houston Astros, based in the Dominican Republic.

At 32, she became the first woman hired as a full-time hitting coach in the majors when the Yankees signed her on as the team’s minor-league hitting coach.

Now 34, the former Lobo catcher is packing up the moving van again, this time headed for Tampa Bay, Fla., and another spot in history. She takes over as manager of the Tampa Tarpons, the Yankees’ Class A affiliate team, becoming the first woman to be called ‘skipper.’

“The first word that comes to mind is gratitude,” Balkovec said in her debut press conference with the Yankees — which was crowded with 112 media participants on Zoom.

Balkovec noted the Yankees’ long history of progressive hiring. (In March 1998, Kim Ng, another former college softball player, was the Yankees’ assistant general manager. Ng went on to be the first female general manager in baseball.) And she tipped her hat to her parents, “who raised me to be a competitive athlete, not a woman or a man, but just to be competitive and capable and aggressive.”

Asked about the sexist blowback to her hiring, Balkovec noted her resiliency.

“Three years ago, I was sleeping on a mattress that I had pulled out of a dumpster in Amsterdam. If you know yourself and you know where you came from, it doesn’t really matter.”

She calls her story “the American dream” and is adjusting to a new level of attention, including some shoutouts from some heroes.

“I can die now,” Balkovec joked. “Billie Jean King congratulated me.”

Balkovec came to UNM from Creighton University, recruited to play catcher for the Lobos. By the time she graduated in 2009, she had changed her major from psychology to exercise science and then to kinesiology, with an eye to a career helping athletes perfect their performances.

Among her mentors were former UNM instructor Chris Frankel and Len Kravitz, associate professor of exercise science at UNM, who taught her that coaching is motivating others to learn.

She had graduated from UNM and was working on her master’s degree in kinesiology at Louisiana State University in 2012, when the St. Louis Cardinals called looking for a student to work as a Minor League strength and conditioning coach at their baseball training camp near Baton Rouge. The Cardinals took a leap of faith and hired Balkovec, who was working as a graduate assistant strength and conditioning coach at the school.

When the internship ended and she had her degree, Balkovec had an enviable resume for a 26-year-old: A master’s degree in sports administration, experience working with athletes on strength and conditioning at two universities and experience with the Cardinals.

She moved to Arizona, one of the hubs of baseball spring training, applied for every job listed in Major League Baseball and waited hopefully.

“I got crickets,” Balkovec said.

The one baseball representative who showed interest in hiring her later called her to let her know that it was her gender, not her qualifications, that scuttled her chances. And he said he had called around to other teams and heard the same story. She appreciated his candor.

“I finally understood,” she said.

With the doors of Major League Baseball closed tight, Balkovec took a job waitressing in Phoenix, volunteered at Arizona State University and entered what she calls “the dark times.”

Some colleges approached Balkovec about openings in strength and conditioning, but always for women’s sports. Even though she had respect for women’s sports, it bothered her that those were the only doors open to her. She dug in.

One of her sisters suggested she apply for jobs as “Rae Balkovec.” She immediately got email responses, but the conversations ended when they reached her on the phone. Balkovec quickly dropped Rae and went back to Rachel.

Finally, the call came from the Chicago White Sox, who hired her as a strength and conditioning coach.

The White Sox job led to a job back with the Cardinals as the Minor League strength and conditioning coordinator. In November 2015, the Astros brought her on as the Latin American strength and conditioning coordinator.

Balkovec spent a lot of time in the Dominican Republic, taught herself Spanish and some salsa moves and got valuable experience in understanding the Major League Baseball system and learning how to interact with young male players.

In between those temporary stints, Balkovec moved to Amsterdam (the place she scored the free mattress) in 2019 to pursue a second master’s degree in biomechanics and work as the apprentice hitting coach for the Netherlands National baseball and softball team.

When she returned to the United States, she was back to the dark days. With two master’s degrees in human movement science and a list of MLB credits on her resume, she took an internship with a technology firm that uses eye tracking to aid hitters and started knocking on MLB’s door again.

When the Yankees hired her as the league’s first full-time female coach, she was 32 and had lived in 15 cities in 12 years.

“When I actually got that job, I had $14 in my bank account,” Balkovec said. “I was broke as a joke.”

She called her parents to tell them she had made history. And to ask them if they could lend her some money to cover her move.

Balkovec nods to her parents for setting the stage for her ground-breaking career.

“My father and mother, they deserve an award,” Balkovec said. “They literally raised three girls to be absolute hellions.”

The Balkovec girls didn’t grow up with gender barriers that told them that certain goals weren’t possible. So Balkovec naively thought she could get any job based on her skills and was brought up short when she learned otherwise.

“This is a little counterintuitive,” Balkovec said, “but I’m glad I was discriminated against. By the time I was full time, I had done multiple internships. I was super prepared. I’m glad my path was difficult and it still serves me to this day.”

Kevin Reese, Yankees vice president of player development, approached Balkovec about the manager job in mid-December.

Reese says there was no agonizing or even much discussion when Balkovec’s name came up as a possibility to fill the Tarpon’s manager slot.

“It’s a no-brainer,” he said. “The feedback was always positive on Rachel. Everybody was on board. This is about her qualifications and her ability to lead.”

What can the Tarpons players expect from their new manager?

“It’s going to be high standards and clear standards. It’s going back to honesty and being direct,” Balkovec said. “Getting every day to matter and every practice to matter, that’s what I’m really passionate about.”

And it should be fun.

“They can definitely expect some loud music in the clubhouse,” she says.

Since getting the skipper job, Balkovec has been working 14-hour days, immersing herself in all aspects of a baseball team. While her experience has been in strength and conditioning and hitting, Balkovec is getting up to speed on fielding and pitching as well as all the aspects of running an organization and team travel.

One aspect of the job has always come easily for Balkovec — developing camaraderie and cohesion among players.

“My goal is really to know the names of the girlfriends, the dogs, the families of all the players,” she said. “My goal is to develop them as young men and young people who have an immense amount of pressure on them. My goal is to support the coaches that are on the staff.”

In Class A, she will have the youngest and least experienced players to work with.

“We’re going to be talking more nuts and bolts of pitching and hitting with them, and defense,” Balkovec said. “It’s really just to be a supporter, and to facilitate an environment where they can be successful.”

Even though she’s a trailblazer, Balkovec has experienced very little sexism on the field or in the clubhouse.

“In 10 years, so little that it’s not even worth mentioning,” she said. Players have a certain level of curiosity when they’re meeting the first female coach they’ve ever known, which Balkovec understands as completely normal.

“I just know within five minutes — my presence in the room, I speak confidently, I’m bilingual — it all just goes away. The players I’ve worked with, I do feel — whether they like me or they don’t like me, they like what I’m saying or they don’t like what I’m saying — they respect me. They do know I’m passionate and hard-working and I know what I’m talking about.”

Balkovec notes that there are now 11 women in uniform in baseball today, so the tide is turning slowly.

“There were many times in my career where I felt extremely lonely and I literally didn’t have anyone to call who had been going through the same experiences,” she said.

Balkovec is active on social media, which she says isn’t about feeding her brand, but inspiring others.

“I want to be a visible idea for young women. I want to be a visible idea for dads that have daughters,” she said. “I want to be out there. It’s something I’m very passionate about.”

Brian Cashman, the Yankees general manager who recruited Ng more than 25 years ago and put the first crack in baseball’s glass ceiling, calls Balkovec “a really impactful, smart person. What’s she’s bringing to the table is her knowledge and her strength and her perseverance and her thoughtfulness and her empathy. She’s as tough as they come.”

Balkovec’s ultimate goal is to be a general manager.

“Right now, I’m a manager,” she said. “I don’t really have a timeline for when I would leave, but I just know in the future, that leadership and the front office is definitely present in my mind.”

I understand that’s a very long-term goal,” she said.

When asked whether she has the skills to go higher in coaching or management, Cashman said, “The sky’s the limit. She’s determined. She’s strong. She’s got perseverance. I would not put any limitations on what her future would entail. She’s willing to go to the ends of the earth to accomplish her goals. This is someone who will not be denied.”

After Balkovec graduated from UNM in 2009, she followed a path of perseverance that led — 11 years later — to a position as minor league hitting coach with the New York Yankees, which led to her current position as manager of the Tampa Tarpons, in the Yankees’ minor league system.

These were moves she made to get there:

2009

Strength and Conditioning Intern: API (Now EXOS)

2010

Strength and Conditioning Graduate Assistant: LSU

2012

Strength and Conditioning Intern: St. Louis Cardinals Major League Baseball

2012

Front Office Internship: Los Tigres Del Licey (La Republica Dominicana)

2013

Strength and Conditioning Internship: Arizona State University

2013

Strength and Conditioning Internship: Chicago White Sox

2014

Minor League Strength & Conditioning Coord: St. Louis Cardinals

2016

Latin American Strength and Conditioning Coordinator: Houston Astros

2018

Minor League Strength and Conditioning Coach: AA Affiliate: Houston Astros

2019

Returned to School for MS in Biomechanics in Amsterdam

2019

Apprentice Hitting Coach: Netherlands National Baseball & Softball programs

2019

Research & Development Intern: Driveline Baseball: Eye Tracking for Hitters

2019

Hired by New York Yankees as an Major League Baseball hitting coach

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

Read MoreUniversity of New Mexico alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca found peace in the written word…

Read MoreIn a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM…

Read MoreAmong campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, UNM has always been distinctly of New Mexico…

Read MoreYou can thank an alumnus for creating the image technology that keeps us connected…

Read MoreWhen I decided to attend UNM I applied to live on campus because I wanted to become involved in student life…

Read More

Jessica Richardson, an associate professor of Speech and Hearing Sciences at UNM, has been awarded a five-year, $2 million grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders to optimize treatment and interventions for those who acquire the language disorder known as aphasia as a result of suffering a stroke.

Aphasia affects speaking, understanding, reading and writing. The most common cause of aphasia is stroke, and 30 to 50 percent of people who have had a stroke will live with aphasia for the rest of their lives.

“Aphasia is a devastating and debilitating diagnosis.,” said Richardson, who has worked with people with post-stroke aphasia, and other acquired cognitive or communication deficits, for more than 20 years. “Just imagine not being able to say what you want to say or understand what others are saying, or not being able to read or write anymore. If you think about your everyday life, and what you do every day that involves any type of language, you can begin to understand how big of an impact this can have.”

One of the big gaps in current treatment that she seeks to address is not taking full advantage of the brain’s plasticity, or ability to change. “We know our brain is plastic and very responsive to use or activity,” Richardson said. “You can change the way the brain works, and even the structure of the brain, with what you do.”

Richardson said patients with aphasia and their recovery team can help the intact brain repair itself by taking advantage of this plasticity. She hopes to combine evidence-based aphasia treatment with a non-invasive brain intervention called transcranial direct current stimulation for even more optimized treatment.

“Depending on where we place the electrodes on the scalp, we can make neurons more ‘interested’ in a task, as the electrical current may increase the probability that they will send brain signals, or fire,” she said. “We can also tell certain neurons to be quiet if they are interfering in some way, using the electrical current to decrease the probability that they will fire. Over time, with repeated exposure to this, we can potentially change the way the brain functions when ‘doing’ language.”

Richardson has seen first-hand how particularly devastating aphasia can be, first as a high schooler after her grandfather suffered from aphasia, and more recently with her mother. “It changes everything about one’s life — identity, autonomy, relationships, financial security … everything,” Richardson said. “And it changes the lives of the loved ones of survivors as well.”

UNM's Jessica Richardson awarded grant to optimize treatment for the language disorder known as aphasia...

For anyone who loves to watch movies and TV shows filmed in New Mexico — hitting “pause” and saying, “Wait, was that the Rio Grande Gorge?” — Jason Strykowski (’07 MA, ’15 PhD) has written your new Bible. Strykowski, a script supervisor and assistant on major film and TV sets, has put together an encyclopedia of 50 well-used filming locations throughout New Mexico. A Guide to New Mexico Film Locations (University of New Mexico Press, 2021) takes an interesting tack: describing the location and its history, including a filmography of productions that have used the location and adding travelogue features that include driving directions and where to stay and eat if you decide to visit. Here’s a fun fact: The first film made in New Mexico, “Indian Day School,” circa 1898, was shot at Isleta Pueblo. It used the new kinetograph visual recording technology and was shown at kinetoscope parlors, the precursor to cinemas. The book is filled with photos, both current and vintage — Kirk Douglas on the set of “Lonely Are The Brave” in Albuquerque, Dennis Hopper at Taos Pueblo for “Easy Rider” and Jimmy Stewart looking tough at Tesuque Pueblo in “The Man From Laramie.”

Hakim Bellamy (’14 MA) was named the inaugural poet laureate for the City of Albuquerque in 2012. The job comes with a two-year term and just a few requirements: implement a community project and respond to occasional requests for poems to commemorate certain events. Commissions y Corridos (University of New Mexico Press, 2021), one of a series of collections of the poems of Albuquerque’s poets laureate, collects many of Bellamy’s commissions along with other poems he wrote during his tenure. Not every poem is about Albuquerque, but as Bellamy explains in his preface, Albuquerque is his love and his muse. The collected poems range from short and sweet, as in “New Mexico Department of Tourism (A Haiku)” and “Albuquerque. Where/the desert doesn’t get in/the way of your view” to long and searching, as in “Law Enforcement Oath of Honor,” in which Bellamy writes his ideal of an officer’s sworn oath. Some lines: “I solemnly swear to be as obsessed with building community as I am with broken laws. I will act justly and impartially and with propriety toward my fellow officers. So long as they are just, impartial and proper toward my fellow citizens.”

The subtitle of Vaccines & Bayonets (Wheatmark, 2021) by Bee Bloeser (’67 MA) is “Fighting Smallpox in Africa Amid Tribalism, Terror and the Cold War.” That’s a sweeping brief for an author to undertake, by for Bloeser it’s the story of one chapter in her life. With two young children, she and her husband, a U.S. Public Health Service nurse, moved to Nigeria to join the United States-led smallpox vaccine campaign in West Africa. That’s the “vaccine” part of Bloeser’s title. The “bayonets” relate to the region’s raging civil war that the family stepped into. With vaccines on everyone’s minds, it is fascinating to read about an all-out push in a foreign nation to vaccinate in order to eradicate a disfiguring and deadly preventable disease. Bloeser’s memoir is breezy and warm and continues through other postings in West Africa as well as in Equatorial Guinea.

Mary A. Johnson (’89 MA, ‘94 PhD) spent her career as a clinical counselor and developed an expertise in counseling people having trouble in their relationships. In her professional capacity, she learned a lot about Asperger’s syndrome. Johnson, a widow, met her second husband, Jim, late in life and moved to Oregon where he lives. Love and Asperger’s: Jim and Mary’s Excellent Adventure (Atmosphere Press, 2021) follows the steps of their courtship and marriage with episodes followed by insights, in italics, that reflect her realization in hindsight that Jim was exhibiting classic signs of someone with Asperger’s. On early dates, Jim opted for a narrow menu of chain restaurants, which she wrote off as quirky. In retrospect she recognized a common trait of people with Asperger’s. Later, after they married, Jim’s seemingly abrupt or rude comments and criticisms hurt her feelings. She saw them in hindsight as examples of a person with Asperger’s not recognizing other people’s emotions and having trouble empathizing. One day over lunch, she decides to tell her husband she thinks he has Asperger’s. He stirs his coffee for a long time and says, “I always wondered why I felt different.”

William E. Foote (’69 BA, ’75 MA) has been a forensic psychologist in Albuquerque for more than 40 years and has taught in UNM’s departments of Psychology and Psychiatry and at the School of Law. So he brings a lifetime of experience to Understanding Sexual Harassment (American Psychological Association, 2021), which he wrote with Jane Goodman-Delahunty. While the book is geared toward forensic clinicians practicing in the area and preparing forensic reports and testimony in court cases, it’s an interesting read for anyone interested in one of the social issues of our times. The book walks through the history of sexual harassment law (did you know that even though the protection against being harassed due to gender is embodied in the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the term “sexual harassment” wasn’t coined until 1970?) It explores who are the most common perpetrators — a range of (mostly) men who can be misogynistic, clueless, rate low in honestly and humility and high in authoritarianism. Anyone can become a victim of workplace harassment, but Foote and Goodman-Delahunty go to the research to show that predators look for certain victims — namely those who have been the victims of previous trauma.

Google is tracking your online browsing. Alexa knows your grocery list. And that Ring doorknob is scanning the front yard. In 1993, Oscar H. Gandy, Jr. (’67 BA) used the phrase “panoptic sort” to describe a sociotechnical system that sorts people on the basis of their estimated value or worth. Panoptic (complete, comprehensive, sweeping) sorting has now entered the age of Big Data and Gandy, professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication, comes with a second edition of The Panoptic Sort: A Political Economy of Personal Information (Oxford University Press, 2021) to explore how surveillance capitalism influences how we are sold everything from shampoo to political candidates. For Gandy, this is cause for concern. He calls for transparency and accountability and collective resistance to the primacy of algorithms.

Middle Eastern Americans are often distrusted, attacked and assailed for their names, religions and dress, spiking in severity after any domestic incident involving terrorism. “It is from this crucible that Middle Eastern American theatre is forged,” writes Michael Malek Najjar (’93 BA) in Middle Eastern American Theatre: Communities, Cultures, and Artists (Methuen Drama, 2021). Creatives in the community explore in their communities and in person conflicts and struggles in theater. Najjar looks at how writers, actors, directors and other performers of Middle Eastern heritage have created a vibrant theater scene. It is a diverse group — Arabs, Jews, Iranians, Armenians and Turks.

“It’s OK. It happens. Please don’t beat yourself up.” So begins a provocatively titled little volume by strategic communications consultant Mandi Kane (’06 BA). In So, You F*cked Up: A Peptalk for When You’ve Made a Mistake (Ardia Books, 2021) Kane gives readers a literal pep talk to get them through personal or professional foul-ups so relationships and reputations aren’t permanently damaged. Lesson No. 1: “You’re not alone.” Lesson No. 2: Regardless of what feelings you’re spinning through — embarrassment, disappointment, frustration, anger — put them aside and get to the task of moving forward. Kane, who in her media relations business helps people and corporations navigate through mistakes, offers strategies for making things right. “Apologize if you need to and be sincere. Saying you’re sorry isn’t a weakness, it’s a strength,” she writes. And she offers warm advice: “You are not defined by your mistakes, no matter how public.”

Cattle rustling. Treasure hunting. Bootlegging. Family drama. New Mexico scenery ranging from Quemado ranches to Gallup dance halls to the spooky Malpais. Death on a Desolate Piece of Ground (Abbott Press, 2021) by Ray Windsor (’71 BAED) takes readers through a mystery set in New Mexico during the Depression. Jesse Woods, one of three sons of a violent and whiskey-drinking Catron County rancher, survives a childhood of beatings, runs away and, barely 16, finds himself taking the rap for his cattle-rustling friends and in prison for a year. Hardened when he gets out, he joins a rustling syndicate and becomes a man who never walks away from a fight. The bullied becomes the bully, culminating in unspeakable violence.

Another richly told New Mexico mystery, Taos Gothic (White Bird Publications, 2021), comes from author James C. Wilson (’82 PhD). This is set in present-day Taos and begins with the disappearance of Kate Isaacs, a Santa Fe historian doing research at the Mabel Dodge Luhan House in Taos. Investigating Isaacs’ disappearance is Fernando Lopez, a retired Santa Fe police detective now hanging out his shingle as a private investigator. Isaacs, a podcaster and UNM lecturer with a past that includes drinking and drugging, is reported missing by her wife in Santa Fe. Last known sighting? At a party at the home of a former lover. If you like Taos, the D.H. Lawrence Ranch and Taos women writers — Willa Cather in particular — this is a page-turner for you.

We would like to add your book to the alumni library in Hodgin Hall and consider it for a review in Shelf Life.

Please send an autographed copy to:

Shelf Life, UNM Alumni Relations

1 UNM, MSC01-1160, Albuquerque, NM 87131

New and notable releases from Ray Windsor, Michael Malek Najjar, Hakim Bellamy, and other UNM alumni…

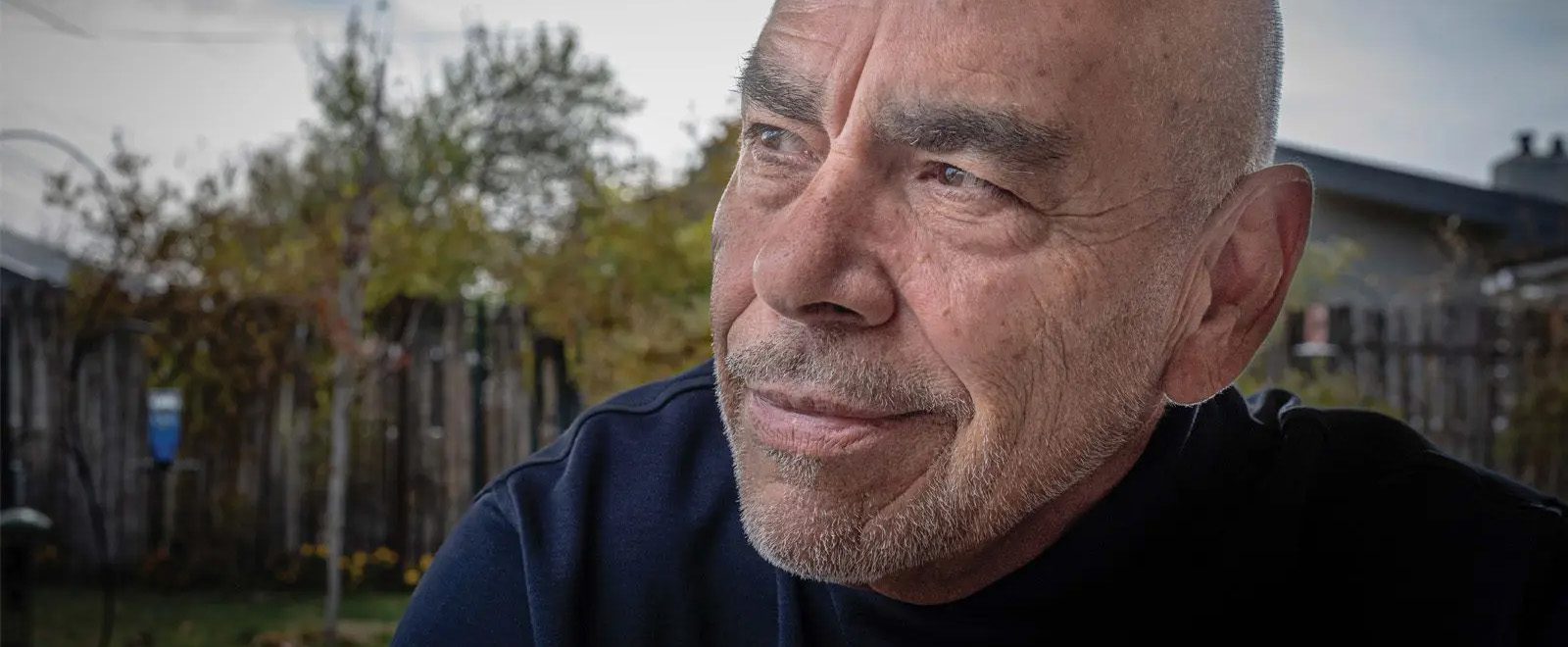

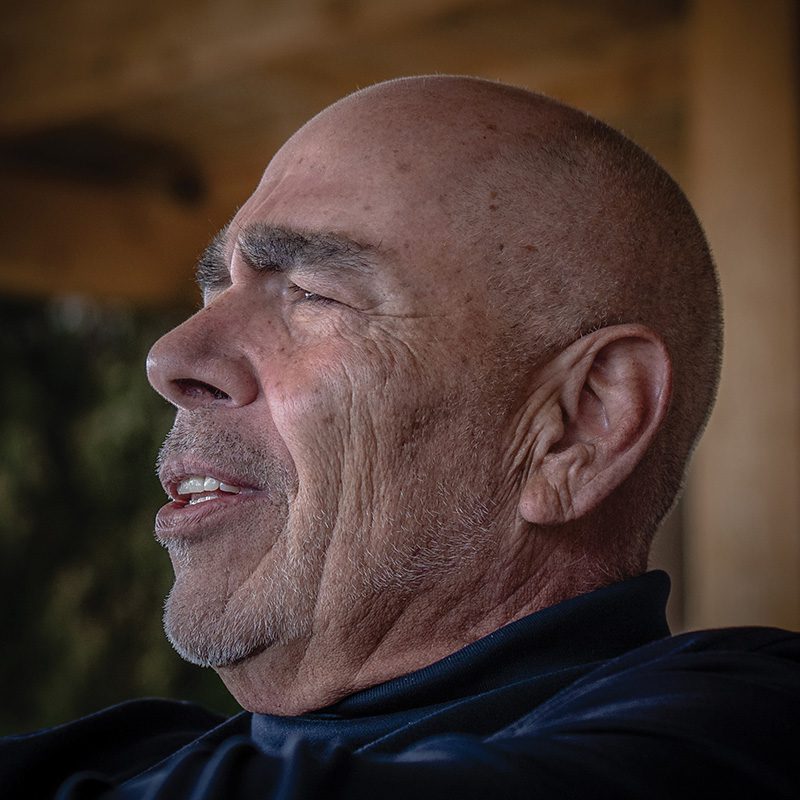

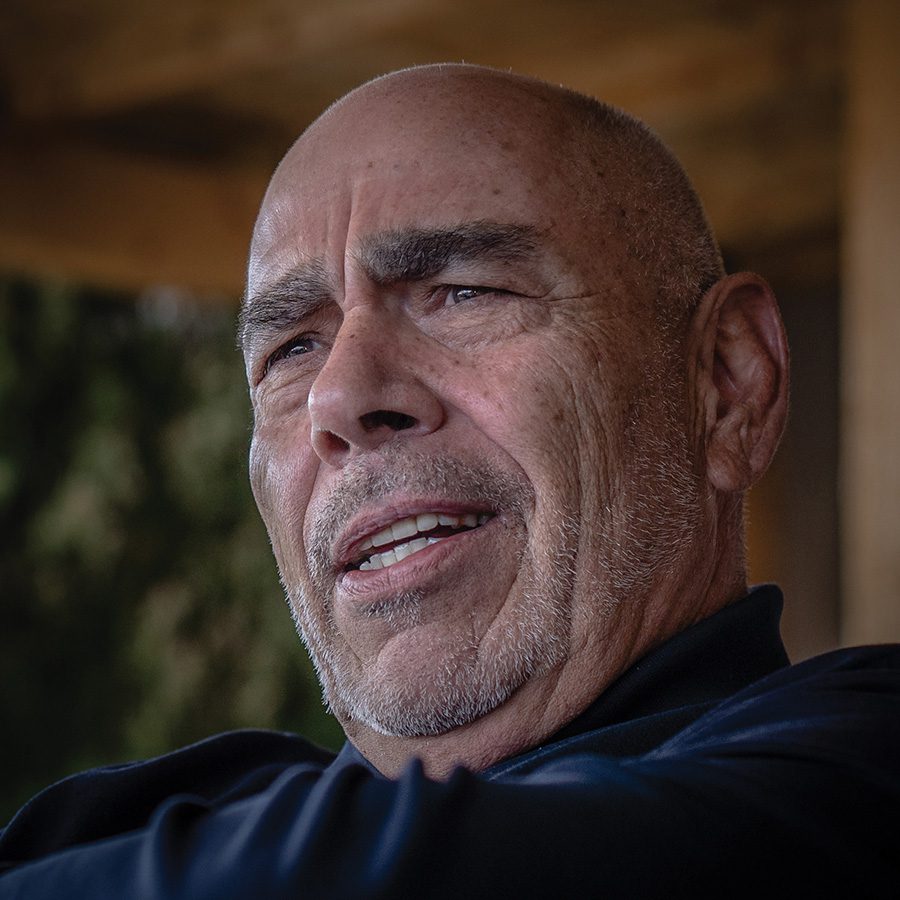

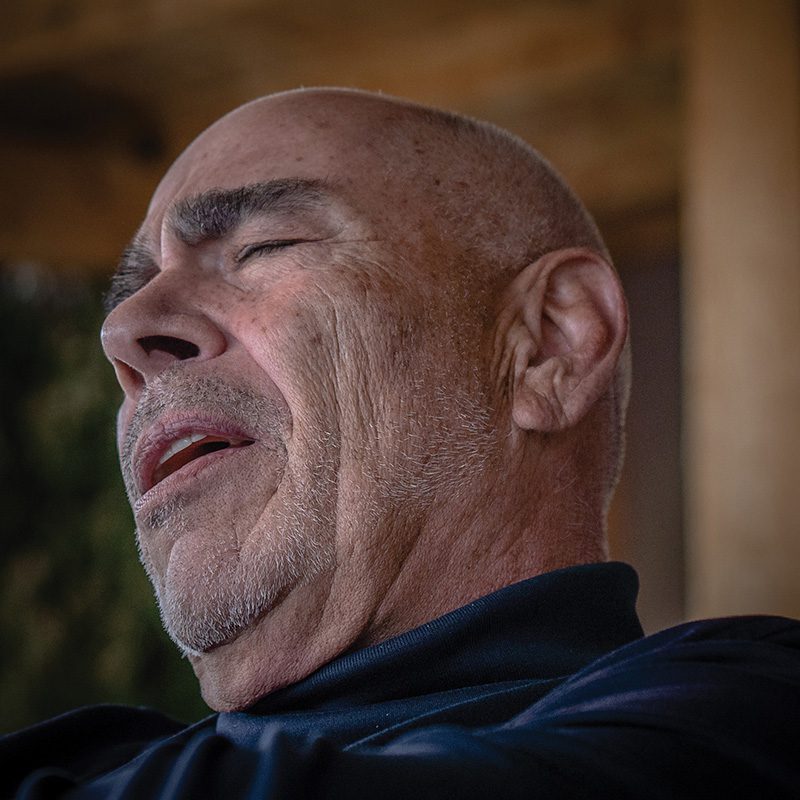

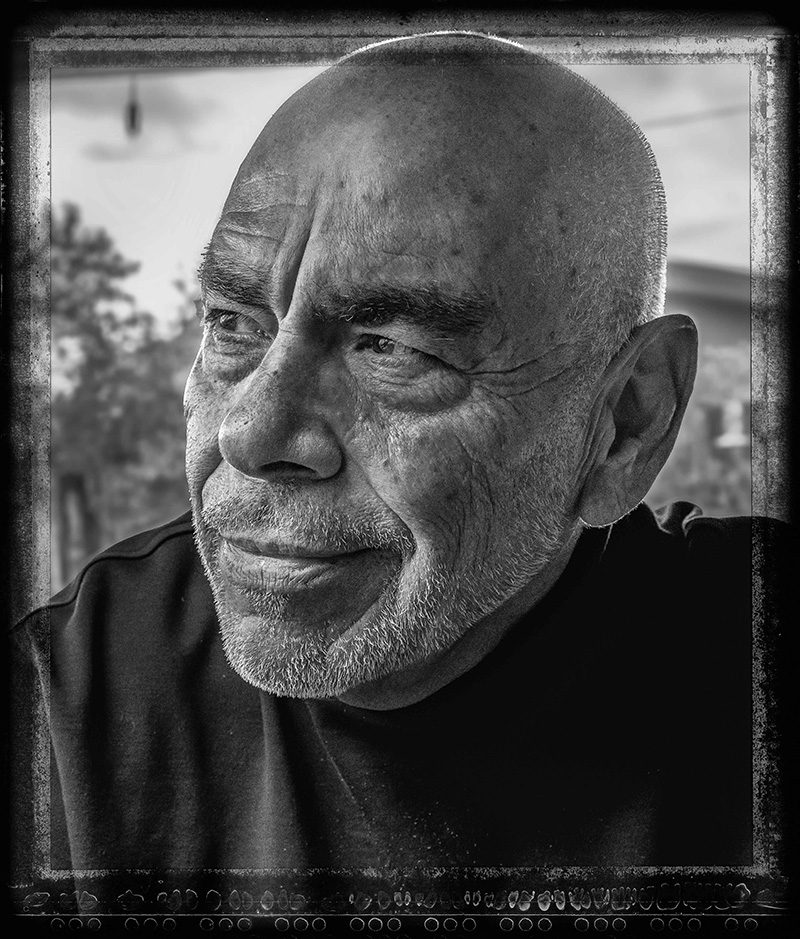

Photos: Roberto E. Rosales (’96 BFA, ’14 MA)

Alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca (’84 BA) found peace in the written word

By Leslie Linthicum

When Jimmy Santiago Baca stands in front of a classroom — maybe it’s a high school in East L.A., or a jail in New Mexico or a seminar at Berkeley or Yale — he’ll challenge aspiring writers to tap into their trauma and find their truth. And he’ll tell them they already have the tools they need: “You have imagination and you have experience,” he’ll say. “That’s where writing comes from.”

And he will likely share his own truth: that books saved his life.

Baca (’84 BA, ’03 HOND), one of the nation’s most prolific and decorated writers, has had 31 books published in 26 languages, and at 70 he still adheres to his morning practice of settling in at the keyboard at 5:30 a.m.

Known primarily as a poet, he also has written novels, short stories and screenplays and is at work on a trilogy while teaching and touring the country reading and lecturing.

It is a charmed life, complete with financial security and a warm family. No one is as surprised and delighted by that as Baca, the former orphan, drinker, drugger and badass criminal.

“A lot of times, no matter how bad things are, I always see myself as being very fortunate,” he says. “There’s not a morning that goes by that I don’t tell the Lord thank you, thank you, thank you.”

His biography has the outlines of a movie and indeed it has been told in a memoir, “A Place to Stand,” published in 2007, and a documentary film in 2014. Born in Santa Fe to a father who drank and was largely absent and a mother who abandoned him and his brother and sister when they were small, he was taken in by his grandparents, then delivered to a Catholic orphanage at age 7, where he lived until he ran away at 13 and was placed in youth detention. At 15, he ran away from there and lived a hand-to-mouth existence, drinking, fighting, getting high, crashing in abandoned homes. Arrested at 17 for a crime he didn’t commit, he spent some time in the county jail before being released. He headed West and was running a lucrative marijuana distribution business in Yuma, Ariz., when he was visiting a heroin dealer’s home as it was raided by federal agents. An agent was shot and Baca was sentenced to five years behind bars for drug possession.

‘I can’t describe how words electrified me.’

He was 20 when he walked into a maximum-security prison in Florence, Ariz., the place where he would teach himself to read and write alone in a cell and begin corresponding with a Good Samaritan who sent him books and paper.

He describes his awakening in “A Place to Stand.”

“I would set my dictionary next to me, prop my paper on my knees, sharpen my pencil with my teeth, and begin my reply. I would try to write the thoughts going through my mind, but they didn’t come out right. They lacked reality. A stream of ideas flowed through me, but they lost their strength as soon as I put them down. I erased so often and so hard I made holes in the paper. After hours of plodding word by word to write a clear sentence, I would read it and it didn’t even come close to what I’d meant to say. After a day of looking up words and writing, I’d be exhausted, as if I had run ten miles. I can’t describe how words electrified me. I could smell and taste and see their images vividly. I found myself waking up at 4 a.m. to reread a word or copy a definition.”

As Baca’s thirst for words grew, he began borrowing books from other inmates.

“Thoreau, Emerson, Dickinson, all the great ones,” he says on a warm morning on the patio of his home in Albuquerque. “Death Row was on the other side of where they kept us, and I was a porter, so I used to be able to go over there and they’d give me their books. They always read the coolest books. Hemingway, Faulkner and a lot of Russian writers. ‘War and Peace’ — come on, that was like my religion.”

Language opened up something in him and what could have been a soul-crushing experience — fights, stabbings, years spent in dark solitary confinement cells because he refused to work — became a rebirth. He fell in love with collections of poems by Shelley, Byron, Neruda and Lorca. He began to review his life through a different lens.

“It was me deciding what I wanted to do with my life,” Baca says. “Me deciding that I probably wouldn’t have made a great criminal but I was really attracted to reading, so I read.”

Sitting alone in the dark for days on end, trying not to go crazy, helped hone writerly skills.

“It was absolutely an opportunity,” Baca says. “You practice your imagination. You practice disembodiment. You practice your memory.”

Baca had plenty of opportunity to practice writing and to dig into the insights and emotions that are the backbone of the poem.

“It was really fortunate to live in a place where death and life met each other every day,” Baca says, “rather than live this passive life where the biggest obstacle is paying the bills and the IRS.”

In exchange for cigarettes or coffee, he wrote poems for other inmates to commemorate events in their lives and to give to their mothers or children or girlfriends. Often, he had to read them aloud to inmates because they couldn’t read.

‘How can you kill and still be a poet?’

When another inmate disrespected Baca and a prison elder advised him he had to fight or be seen as vulnerable as he served out the rest of his time, he came to the realization that his life was changed.

As he recounts in his memoir, he was in the clutch of the fight with the other inmate lying on his back.

“He was partially unconscious, stunned, bleeding from a cracked cheekbone. He took out a shank he’d hidden beneath his sock and I grabbed it. I was standing over him, my feet planted on each side of his shoulders. In that moment, all I could see was his face, the blood pouring out from a wound in his cheek where a bone was exposed. In that moment, everything seemed so calm and quiet. I gripped the shank to stab him. For a second, every horrible thing that had happened to me in my life exploded to the surface as if had been building up to this moment. The blade in my hand, my legs spread over his chest, I loomed over him, staring into his eyes and then at his heart. While the desire to murder him was strong, so were the voices of Neruda and Lorca that passed through my mind, praising life as sacred and challenging me: How can you kill and still be a poet? How can you ever write another poem if you disrespect life in this manner? Do you know you will be forever changed by this act? It will haunt you to your dying breath.”

He chose to become a poet. By the time he was released with $20 and the clothes he entered prison in, Baca had sold some poems to Mother Jones magazine and had contacts with other writers and editors. He went to North Carolina and got his GED and took some community college classes.

Then he returned to New Mexico and had his first collection of poems, “Immigrants in Our Own Land,” published in 1979 and began to make a life as a writer. By the early 1980s, Baca had married, had a baby and bought a fixer-upper. How to pay a mortgage as a poet? Baca enrolled in UNM.

“I needed some money to pay the mortgage and they were offering these Pell grants,” Baca explains. “I had no interest in going to school, but when I got there, I loved it.”

He studied literature, of course, and a new way of looking at books opened up for him.

“I loved the environment of being around so many books. And I really loved the professors,” Baca says. “They had so much to offer. It was like talking to convicts on the yard about writing, but these guys knew all about literature.”

He graduated in 1984 and broke out several years later with the publication of “Martin & Meditations in the South Valley” in 1987, which won the American Book Award and the Pushcart Prize. He won the Taos Poetry Circus — the mother of slam poetry contests — in 1992 and 1993. In 1995 he was invited by PBS journalist Bill Moyers to be part of a televised series on poetry.

Ben Daitz, M.D., a family medicine physician at UNM and a writer himself, met Baca in the poetry slam days and they have remained friends for 40 years.

“His history is pretty dramatic and I think it took him awhile to settle down,” says Daitz, now professor emeritus at the UNM School of Medicine and a documentary filmmaker. “But he did. I think he’s mellowed. He’s more comfortable in his own skin. Part of that is getting older and growing out of his rebellion. And he’s got a great family that is very important to him.”

Baca divorced, married a second time and has four children, one still at home. He has held endowed chairs at Colorado College, Yale and University of California, Berkeley, among other colleges and universities. While he has traveled the world reading, speaking and teaching, he spends more time now in New Mexico, riding his bike, running in the bosque, volunteering as a writing teacher in schools and putting on an annual writer’s retreat. Teaching, as much as writing, has been a foundation of Baca’s life.

“It’s just the service that I think I’m obligated to undertake,” he says. “I was given a great gift. I don’t just want to get rich and famous. I want to spread it around.”

Look for a friend on every page! Send your alumni news to Mirage Editor. Or better yet, email your news to alumni@unm.edu.

Please include your middle name or initial and tell us where you’re living now.

The University of New Mexico Alumni Association

MSC 01-1160, 1 University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, NM, 87131-0001

Deadlines:

Spring deadline: January 1

Fall deadline: June 1

James V. Neely (’51 BSME, ’57 MS), Denver, Colo., has published “Beauty is My God.”

Charles M. Atkinson (’63 BFA), Würzburg, Germany, was conferred the degree of doctor honoris causa by the University of Würzburg for his research in the field of medieval music.

Michael J. Mullins (’69 BBA), Albuquerque, and his wife, Shirley Mullins, celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary on October 9.

Malcolm K. Shuman (’69 MA), Baton Rouge, La., along with his team of archaeologists, surveyed and uncovered a 600- to 800-year-old Native American mound, unearthing materials such as pottery, stone artifacts and tools for future study and preservation.

Virginia Sue Cleveland (’70 BAED), Rio Rancho, N.M., was inducted into the New Mexico Coalition of Educational Leaders Hall of Fame.

Anne M. Hillerman (’72 BA), Santa Fe, N.M., won the 2021 Rounders award, which is presented by the New Mexico Department of Agriculture. Given in recognition of her writing, the Rounders award is presented to those who live, promote and articulate the Western way of life.

Carla Damler Ward (’72 BS), Sandia Park, N.M., has published “The Tinker of Tinkertown.”

Jeanette J. Williams (’72 MA), Dallas, Texas, featured her artwork of cats and dogs at the Gallery With a Cause, located at the New Mexico Cancer Center.

Stanley M. Hordes (’73 MA), Albuquerque, along with his wife Helen Hordes, celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary on June 20.

Veronica C. Garcia (’74 BAED, ’80MA, ’03 EDD), Albuquerque, retired as superintendent of Santa Fe Public Schools after serving 48 years in the New Mexico education system.

Martin J. Chavez (’75 BUS), Albuquerque, former mayor of Albuquerque, has been appointed by Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham as the state’s new infrastructure advisor.

Walter Nygard (’75 BA), Teaneck, N.J., studio manager for Frontline Paper, was one of the artists featured in “This is Not a War Story,” currently streaming on HBO Max.

Joy Harjo (’76 BA), Tulsa, Okla., has become the second person in history to serve three terms as the United States Poet Laureate. She has recently published “Poet Warrior: A Memoir.”

Richard J. Bando (’79 BSCIS), and Jeanne Bando, Venice, Fla., celebrated 50 years of marriage on July 31.

Clyde F. Aragon (’80 BA), Albuquerque, has published “Behind the Electric Iron Curtain.”

Sandra Davis Ferris (’80 MS), Edgewood, N.M., celebrated her 60th wedding anniversary with husband Charles Ferris.

Richard G. Marlink (’80 DM), Princeton, N.J., is among the newest additions to the Scientific Advisory Board of First Wave BioPharma, Inc., specializing in clinical development of treatments for gastrointestinal diseases.

Darby L. Karchut (’82 BA), Colorado Springs, Colo., won the 2021 High Plains Award for her novel “On a Good Horse.”

John A. Garcia (’83 BBA), Albuquerque, is the new secretary of the New Mexico General Services Department.

Mike A. Hamman (’83 BSCE), Albuquerque, was appointed by Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham as the state’s water advisor. In this role he will be working to ensure the state’s water infrastructure is prepared for the effects of climate change and ensure the state implements responsible water management practices.

Audie E. Hittle (’83 BSEE), Aldie, Va., chief architect and chief technology officer at ManTech, an IT solutions firm, was named one of Potomac Officers Club’s Five GovCon Chief Architects to Watch.

Susan Musgrave (’83 MBA), Albuquerque, was named senior vice president of DOE Mission Support Services for Westech International, Inc.

Jesus M. Quinones (’83 MA), Albuquerque, retired after teaching Spanish for 25 years at Albuquerque Public Schools.

Mary-Margaret “Maggie” Brandt (’84 BS, ’90 MD), Oklahoma City, Okla., was named #VeteranOfTheDay by blogs.va.gov on December 16, 2021. During her military career, she received four commendation medals. Since retiring at the rank of colonel, she has served as professor and burn director at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

Casey A. DeRaad (’85 BSEE, ’92 MS), Albuquerque, was named one of Albuquerque Business First’s 2021 Women of Infuence for her efforts in establishing NewSpace New Mexico.

Laura E. Valdez (’85 BA, ’95 MA), Albuquerque, was given the Pillars of Professionalism award by the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators.

Barbara Vigil (’85 JD), Santa Fe, N.M., retired as chief justice of the New Mexico Supreme Court after serving for more than 20 years on the bench and has stepped into her new role as secretary of the Children, Youth & Families Department.

Sandra K. Begay (’86 ASPE, ’87 BSCE), Albuquerque, was presented with the Women in Technology Award by the New Mexico Technology Council in recognition for her contributions to research, mentorship and community impact.

James C. Hoppe (’87 BA), Marblehead, Mass., vice president and dean for Campus Life at Emerson College, was given the Pillars of Professionalism award by the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators.

Kelly J. McBurnette-Andronicos (’87 BFA), Lafayette, Ind., marked the West Coast premiere of her play “The Hall of Final Ruin” at Ophelia’s Jump theatre in Upland, Calif.

Randall D. Roybal (’88 BA), has retired as executive director and general counsel of the New Mexico Judicial Standards Commission after 24 years of service.

Anna C. Hansen (’89 BFA, ’92 MA), Santa Fe, N.M., serving District 2 on the Santa Fe County Commission, was elected to serve as president of the Northern Rio Grande National Heritage Area.

Tracey A. Milligan (’89 BA), White Plains, N.Y., director of Neurology at New York Medical College School of Medicine and chair of the New York Medical College Department of Neurology, has been named “Westchester County Neurologist to Watch” by Westchester Magazine.

Todd Glasenapp (’90, MA), Page, Ariz., worked in the Page schools as a counselor for 22 years and is now working in community mental health as he approaches full retirement.

Sarah Z. Sleeper (’90 BA), Rancho Santa Fe, Calif., has published “Gaijin.”

Sandra S. Fahrlender (’93 BBA), and Robert Fahrlender (’97 BS), Albuquerque, have founded Hole in the Heart, a nonprofit promoting awareness of congenital heart defects.

Alice M. Webb (’93 BFA, ’03 MA), Wauwatosa, Wis., was Magpie Jewelry & Metals Studio LLC’s featured artist for the months of October and November.

Robert A. Lombardi (’94 PhD), Middletown, Pa., executive director of the Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic Association, has been named to the National Federation of State High School Associations board of directors.

Craig A. Herrera (’95 BA), Seattle, Wash., a five-time local Emmy award-winning meteorologist, has joined Fox News Media’s streaming weather service, which launched in October.

Heather A. Dumas (’96 BS, ’00 MBA), Littleton, Colo., joined Ardent Mills LLC as chief people officer. In this role she will be responsible for human resources, internal communications and people management.

Neil Flowers (’96 MA), Los Angeles, Calif., has published “Polyphonic Lyre.”

Lesha D. Harenberg (’96 BS), Albuquerque, teacher at El Dorado High School, received the Golden Apple Award. She has taught at El Dorado for more than 20 years and in 2011 founded a clothing bank at the school.

Matthew K. Montano (’96 BA), Bernalillo, N.M., began his term as Bernalillo Public School’s district superintendent on August 1.

Danielle A. Duran (’97 MBA), Los Alamos, N.M., is the new Intergovernmental Affairs manager for Los Alamos County.

Peter W. Gutowsky (’97 MCRP), Bend, Ore., has stepped into the role of Deschutes County Community Development director and will oversee the county’s land use, code compliance and watewater systems.

Dana M. Northcutt (’97 BA, ’02 MS), Indianapolis, Ind., long-time Commissioner of Officials for the New Mexico Activities Association, has begun her new role as director of Officiating Services for the National Federation of State High School Associations, based in Indianapolis.

David Herrera Urias (’97 BA, ’01 JD), Corrales, N.M., attorney at Freedman Boyd Hollander Goldberg Urias & Ward, has been nominated to serve on the U.S. District Court for the District of New Mexico.

Tyanna L. Lovato (’98 BS, ’14 PhD), Albuquerque, was named one of UNM Advance’s 2021 Women in STEM award winners.

Howard L. Kaibel III (’99 BUS, ’02 MFA), Albquerque, has joined M’tucci’s Restaurants as brand manager and minister of culture.

Marsha D. Kuhnley (’99 BA, ’03 MBA), Albuquerque, has published “Assault on the Afterlife.”

Mina Le Liebert (’99 BSHE, ’00 MS), Colorado Springs, Colo., was named one of 2021’s Women of Influence by the Colorado Springs Business Journal for her work in the public health field.

Bidtah N. Becker (’00 JD), Fort Defiance, Ariz., was appointed by California Gov. Gavin Newsom as deputy secretary for Environmental Justice, Tribal Affairs and Border Relations at California’s Environmental Protection Agency. A member of the Navajo Nation, Becker has become known as one of the nation’s leading tribal environmental justice practitioners.

Freddie J. Bitsoie (’00 AALA), Gallup, N.M., has published the cookbook, “New Native Kitchen: Celebrating Modern Recipes of the American Indian.”

Joshua Brown (’00 BA), Albuquerque, a graduate of the Albuquerque Police Department’s 82nd cadet class, has been promoted to deputy chief and will serve as commander of the Valley Area Command.

Alfredo V. Moreno ('00 BA), Beaverton, Ore., was elected to the board of directors for the Tualatin Hills Park & Recreation District, the largest special park district in Oregon.

Virginia Urias-Sandoval (’00 BA, ’16 MA), Albuquerque, is chief of staff for the executive vice president for UNM Health Sciences. She was previously executive director of the Executive and Professional Education Center at the UNM Anderson School of Mangagement.

Briana H. Zamora (’00 JD), Albquerque, former New Mexico Court of Appeals judge, has been named to the New Mexico Supreme Court.

Christopher D. Arndt (’02 MD), Albuquerque, was named chair the Department of Anesthesiology & Critical Care Medicine in the UNM School of Medicine.

Patricia Dominguez (’02 BS), Bernalillo, N.M., has been appointed the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development director for New Mexico.

Chad Ray (’02 BS), Dallas, Texas, has been named partner at the law firm of Carrington, Coleman, Sloman & Blumenthal, LLP.

Kee J. E. Straits (’02 MA), Albuquerque, founder and CEO of Tinkuy Life Community Transformations, has been hired by Bosque School as director of equity, community and culture.

Andres K. Calderon (’03 MBA), Lubbock, Texas, has retired after 20 years of federal government service, including positions as a Foreign Service officer for the Department of State, program analyst for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Inspector General and Peace Corps volunteer in Kenya.

Wade L. Jackson (’03 JD), a lawyer with Sutin, Thayer & Browne, was voted the Best Corporate Attorney in the Albuquerque Journal 2021 Readers’ Choice selection. He currently serves as chair of Sutin’s Commercial Practice Group.

Megan E. McCoy-Vialpando (’03 BSN), Rio Rancho, N.M., has joined the Prebyterian Medical Group’s team of certified nurse practitioners.

Lisa M. Mercado (’03 BS), Albuquerque, certified physician assistant, was hired by Lovelace Medical Group in the Emergency General Surgery department.

Candace A. Sall (’03 MA), Columbia, Mo., is the new director of the Museum of Anthropology and American Archaeology Division at the University of Missouri.

Katie V. Williams (’04 BA), Albuquerque, associate director of the UNM Alumni Relations Office, was recognized with the Gerald W. May Outstanding Staff Award for her significant contributions to UNM.

Ryan M. Lacen (’05 BUS), Albuquerque, wrote and directed “All the World is Sleeping.” The film explores the struggles of a New Mexican mother struggling with addiction.

Erica T. Lujan (’05 BSED), Los Lunas, N.M., joined Lovelace Medical Group’s Westside Hospital Sleep Center.

Angelica M. Bruhnke (’06 BBA), Rio Rancho, N.M., was named one of Albuquerque Business First’s 2021 Women of Influence for her work as president of RS21 Health Lab.

Jai McBride Calloway (’07 BS), has joined consulting firm Exude, Inc., as a director of diversity, equity and inclusion with a focus on strategy, policy and training.

Amanda C. Chavez (’07 BSED), Santa Fe, N.M, was named Santa Fe Public School district’s new special education director.

Judy A. Liesveld (’07 PhD), Edwardsville, Ill., has been appointed dean of the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Nursing after years of service at the UNM College of Nursing.

Elaine P. Lujan (’07 JD), Albuquerque, previously with the New Mexico Attorney General’s Office, has been appointed judge in the Second Judical District Court.

Jennifer M. Gill (’08 BBA, ’14 DM), Albuquerque, board certified obstetrician and gynecologist, has been hired by Prebyterian Medical Group.

Jesse D. Hale (’08 BA, ’13 JD), a lawyer at Sutin, Thayer & Browne, has been appointed to serve as co-chair of the American Bar Association Health Law Section’s Membership Committee. He most recently served two consecutive terms as one of the ABA committee’s vice chairs.

Shannon E. Kunkel (’08 BA), Albuquerque, is the new executive director for the New Mexico Foundation for Open Government, a nonprofit organization that seeks to defend transparency and open record laws in the state.

Melissa Nunez (’08 BBA), Albuquerque, advisor at CLA Wealth Advisors LLC, was named one of Albuquerque Business First’s 2021 Women of Infuence.

Aaron B. Zimmerman (’08 BS), Austin, Tex., assistant professor with the University of Texas at Austin, was honored with the Teaching Excellence Award in the College of Natural Sciences.

Rachel A. Balkovec (’09 BS), Tampa, Fla., was named manager of the New York Yankees’ affiliate Tampa Tarpons.

Sarah Sayles (’09 MA), Safford, Ariz., has begun her position as executive director of the Gila Watershed Partnership of Arizona, a nonprofit organization seeking to improving the water and ecological condition of the surrounding region.

Deborah R. Stambaugh (’09 JD), Alexandria, Va., joined the litigation department at Wisler Pearlstine, LLP.

Christie L. Abeyta (’10 BAED), Española, N.M., is the new superintendent for the Santa Fe Indian School.

Cameron M. Decker (’10 BAFA), Arlee, Mont., is educator and outreach coordinator at the Missoula Art Museum, responsible for developing art education programs and implementing statewide distance learning sessions.

Diana V. Martinez (’10 BA, ’17 MPH), Albuquerque, was recognized with the Gerald W. May Outstanding Staff Award for her significant contributions to UNM during her time with the Health Sciences Learning Environment Office.

Jodi E. Shadoff (’10 BA), Orlando, Fla., competed in the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics respresenting Great Britain in women’s golf.

Sean P. Ward (’10 BA), Albuquerque, is executive director of the Democratic Party of New Mexico.

Matthew J. Armijo (’12 BA), Santa Fe, N.M., has joined the Montgomery and Andrews law firm in Santa Fe, specializing in environmental law, commercial disputes, products defects, construction defects, oil and gas litigation and personal injury.

Justin L. Greene (’12 BBA), has joined Sutin, Thayer & Browne as an associate attorney. As a member of the firm’s Litigation Group, he practices primarily in the areas of employment law and commercial litigation.

Jessica R. Martin (’12 JD), has joined Sutin, Thayer & Browne as an associate attorney in the firm’s Litigation Group, focusing on commercial litigation. She is fluent in Spanish, providing written and oral communication in Spanish and English for clients.

Claudia Sanchez (’12 MA), Albuquerque, has been promoted to director of marketing and policyholder services by New Mexico State Mutual.

Emily B. Allen (’14 MBA, ’14 MEMBA), Corrales, N.M., chief financial officer of Dekker/Perich/Sabatini, was named one of Albuquerque Business First’s 2021 Women of Infuence.

Grant A. Burrier (’14 PhD), Stow, Ohio, is visiting associate professor in the Department of Integrative and Global Studies at Worcester Polytechnic Institutute.

Manon K. De Roey (’14 BA), Albuquerque, competed in the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics respresenting Belgium in women’s golf.

Rhiannon L. Samuel (’14 BA), Albuquerque, executive director of Viante New Mexico, was named one of Albuquerque Business First’s 2021 Women of Influence.

Samuel D. Saunders (’14 BBA), Albuquerque, won the L&J Golf Championship, hosted by Jenning Mill Country Club in Watksinville, Ga.

Chanel R. Wiese (’14 BBA, ’18 MBA), Albuquerque, was named one of Albuquerque Business First’s 2021 Women of Infuence in recognition of her leadership in launching the Somos Unidos Foundation.

Noe Astorga-Corral (’15 BA, ’19 JD), a lawyer with Sutin, Thayer & Browne, has become licensed to practice in the Navajo Nation. Astorga also heads Sutin’s Committee on Equality, which works to tangibly empower marginalized communities in New Mexico. He is fluent in Spanish.

Django Lovette (’15 BA), represented Canada in the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics in the high jump and finished in 8th place.

Julie A. Morrison (’15 BA), Albuquerque, was recognized with the Gerald W. May Outstanding Staff Award for her significant contributions to UNM in the Physics and Astronomy Department.

Xochitl Torres Small (’15 JD), Las Cruces, N.M., was confirmed by the U.S. Senate to serve as U.S. Department of Agriculture undersecretary for rural development.

Ryan Inzenga (’16 MBA), Zachary, La., has joined Luba Workers’ Comp as vice president and underwriting manager.

Aaron P. Rivera (’16 BA), Corrales, N.M., ProView Networks sports announcer, is the new play-by-play announcer at Fort Marcy Ballpark, calling home games for the Santa Fe Fuego.

Amalia Sanchez-Parra (’16 BS, ’21 PhD), Albuquerque, was named one of UNM Advance’s 2021 Women in STEM award winners.

Troy S. Lawton (’18 BA, ’21 JD), Rio Rancho, N.M., has joined the Montgomery and Andrews law firm in Santa Fe, specializing in federal taxation law, buisness law and legal writing.

Adriana E. Oñate (’18 MARCH), El Paso, Tex., was recognized as one of Mile High CRE’s “Movers and Shakers,” in honor of her achievements in architecture and design.

Christopher J. Pommier (’18 JD), Santa Fe, N.M., has joined the Montgomery and Andrews law firm in Santa Fe.

Brooke B. Sheldon (’18 BS), Albuquerque, received the Fulbright Research Award for the 2021-2022 academic year and will pursue research of the Portuguese dialects and their influence on the Lusophone world.

Alex G. Elborn (’19 JD), has joined Sutin, Thayer & Browne as an associate attorney in the firm’s Litigation Group. His practice focuses on commercial litigation, employment law and probate matters. He speaks and writes in Spanish.

Mingjie L. Hoemmen (’19 JD), has joined Sutin, Thayer & Browne as an associate attorney. She joins the firm’s Litigation Group, where she practices primarily in the areas of employment law and civil rights, collections, bankruptcy and creditors’ rights. She is fluent in Mandarin Chinese.

Thatcher A. Rogers (’19 MS), Albuquerque, received the Friends of Coronado Historic Site scholarship and a grant from the University of Missouri Research Reactor Archaeometry Laboratory.

Justin D. Armbruester (’21 BBA), Sammamish, Wash., was called up in Round 12 of the Major League Baseball draft by the Baltimore Orioles.

Kristen Burby (’21 JD), White Rock, N.M., has joined the Montgomery and Andrews law firm in Santa Fe, specializing in natural resource and environmental law.

Ava Cohen (’21 BBA), Albuquerque, represented Israel in the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics in the 300-meter steeplechase.

Amanda E. Cvinar (’21 JD), has joined Sutin, Thayer & Browne as an associate attorney. A member of the firm’s Commercial Group, she practices primarily in the areas of corporate law, intellectual property, public finance, estate planning and renewable energy development.

New and notable releases from Ray Windsor, Michael Malek Najjar, Hakim Bellamy, and other UNM alumni…

Recent Comments