“UNM’s sense of place is unmistakable.”

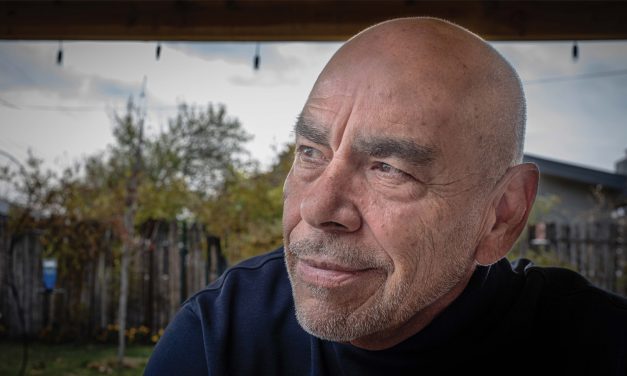

V.B. Price (’62 BA) Author

Form and Function

“It takes more than the profile or outward appearance of its buildings to make a university, but if aesthetics mean anything in the intellectual development of students, and I feel certain that it does, then The University of New Mexico has an asset which gives it a unique position among the institutions of the nation.”

– Thomas L. Popejoy UNM president, 1948 – 1968

Unique and unmistakable, indeed. Among college campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, The University of New Mexico has always been distinctly of New Mexico. A visitor walking onto campus for the first time would never mistake her location for Seattle or Savannah, New Haven or Nebraska.

It wasn’t always so. In 1892, UNM was one building — a three-story red brick structure with a pitched gabled roof that would have looked at home anywhere back East. It was University President William G. Tight, who, as luck would have it, was a scholar of ancient Pueblo culture and a visionary, who began to build the campus that we know today. In 1908, he oversaw a remodel of what is now known as Hodgin Hall, adding beams, corbels and rounded stuccoed forms that are the unmistakable look and feel of adobe pueblos.

As Main Campus grew, each additional building adopted the same style — Spanish-Pueblo Revival — often at the hand of noted architect John Gaw Meem, who served as the campus architect from 1934 to 1956. In 1959, with the adoption of the Long-Range Campus Development Plan, the UNM Board of Regents agreed to preserve Pueblo Revival architectural style. The policy as it stands today reads:

“It is the policy of the University that all buildings constructed on the central campus continue to be designed in the Pueblo Revival style and that buildings on the north and south campuses reflect the general character of this style to the extent possible given the special needs for facilities in these areas.”

But form naturally follows function. And as the University has grown and education has become more technical, with laboratories, energy-saving and safety goals and many more students, staff and faculty, campus architecture has modernized. The goal is to preserve the original feel, not make new buildings larger cookie-cutter impersonations of the old.

“It’s a balance,” says Douglas Brown, chair of the Board of Regents. As he looks around Main Campus today, he is pleased to see new buildings in harmony with the old — not mimics but kinsfolk.

George Pearl Hall, the home of the College of Architecture & Planning along Central Avenue, is a striking example of ushering Pueblo Revival into the 21st century. The newest additions or major renovations on Main Campus pictured in these pages — Farris Engineering Center, which opened in late 2017; McKinnon Center for Management, which was completed in 2018; the Physics & Astronomy and Interdisciplinary Science building, or PAÍS, which was completed late last year; and Johnson Center, which opened this year — are undeniably modern but maintain common ancestry with the Meem style: flat roofs, low profiles, color-conforming stucco.

“I think it’s never looked better,” Brown says. Adaptation to the times even had the endorsement of Meem. “I get quite a bit of exhilaration when I visit the campus,” he said later in his life. “Sure, yes, they have all departed from the Pueblo Style, but people have to experiment a little bit. They have to have a little freedom to keep the campus alive. When you forbid these things, it starts dying.”

Spring 2022 Mirage Magazine Features

Big League

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

Read MoreFrom Prison to Poet

University of New Mexico alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca found peace in the written word…

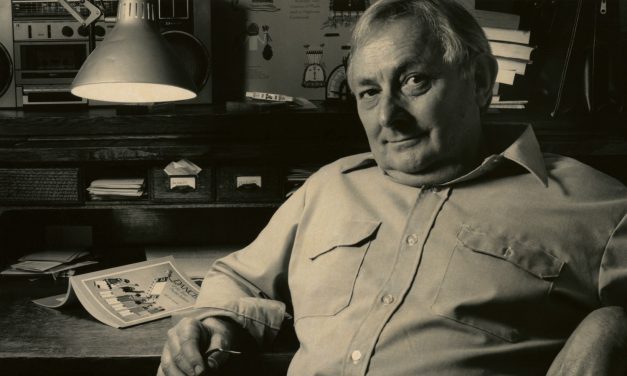

Read MoreProfessor Hillerman

In a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM…

Read MoreForm and Function

Among campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, UNM has always been distinctly of New Mexico…

Read MorePicture Perfect

You can thank an alumnus for creating the image technology that keeps us connected…

Read MoreMy Alumni Story: Joshua Whitman

When I decided to attend UNM I applied to live on campus because I wanted to become involved in student life…

Read More