Jogging Memory

Jessica Richardson, an associate professor of Speech and Hearing Sciences at UNM, has been awarded a five-year, $2 million grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders to optimize treatment and interventions for those who acquire the language disorder known as aphasia as a result of suffering a stroke.

Aphasia affects speaking, understanding, reading and writing. The most common cause of aphasia is stroke, and 30 to 50 percent of people who have had a stroke will live with aphasia for the rest of their lives.

“Aphasia is a devastating and debilitating diagnosis.,” said Richardson, who has worked with people with post-stroke aphasia, and other acquired cognitive or communication deficits, for more than 20 years. “Just imagine not being able to say what you want to say or understand what others are saying, or not being able to read or write anymore. If you think about your everyday life, and what you do every day that involves any type of language, you can begin to understand how big of an impact this can have.”

One of the big gaps in current treatment that she seeks to address is not taking full advantage of the brain’s plasticity, or ability to change. “We know our brain is plastic and very responsive to use or activity,” Richardson said. “You can change the way the brain works, and even the structure of the brain, with what you do.”

Richardson said patients with aphasia and their recovery team can help the intact brain repair itself by taking advantage of this plasticity. She hopes to combine evidence-based aphasia treatment with a non-invasive brain intervention called transcranial direct current stimulation for even more optimized treatment.

“Depending on where we place the electrodes on the scalp, we can make neurons more ‘interested’ in a task, as the electrical current may increase the probability that they will send brain signals, or fire,” she said. “We can also tell certain neurons to be quiet if they are interfering in some way, using the electrical current to decrease the probability that they will fire. Over time, with repeated exposure to this, we can potentially change the way the brain functions when ‘doing’ language.”

Richardson has seen first-hand how particularly devastating aphasia can be, first as a high schooler after her grandfather suffered from aphasia, and more recently with her mother. “It changes everything about one’s life — identity, autonomy, relationships, financial security … everything,” Richardson said. “And it changes the lives of the loved ones of survivors as well.”

Campus Connections

LatestJogging Memory

UNM's Jessica Richardson awarded grant to optimize treatment for the language disorder known as aphasia...

Spring 2022 Mirage Magazine Features

Big League

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

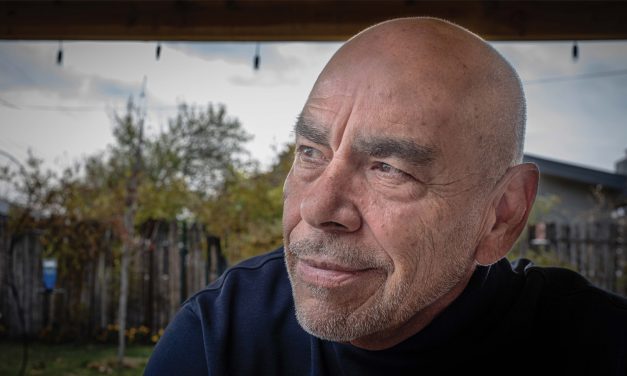

Read MoreFrom Prison to Poet

University of New Mexico alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca found peace in the written word…

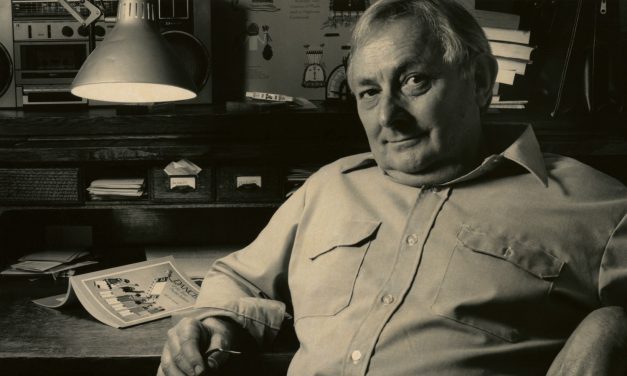

Read MoreProfessor Hillerman

In a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM…

Read MoreForm and Function

Among campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, UNM has always been distinctly of New Mexico…

Read MorePicture Perfect

You can thank an alumnus for creating the image technology that keeps us connected…

Read MoreMy Alumni Story: Joshua Whitman

When I decided to attend UNM I applied to live on campus because I wanted to become involved in student life…

Read More