Big League

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

Read More

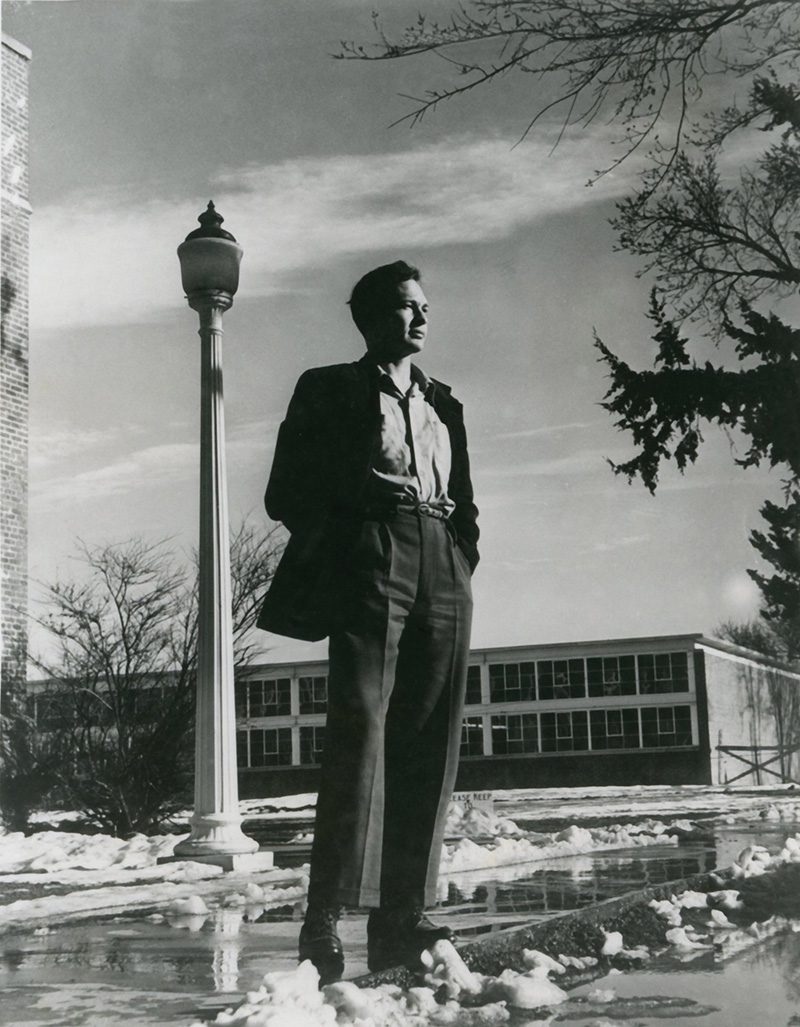

Photos: Tom Lazarevich

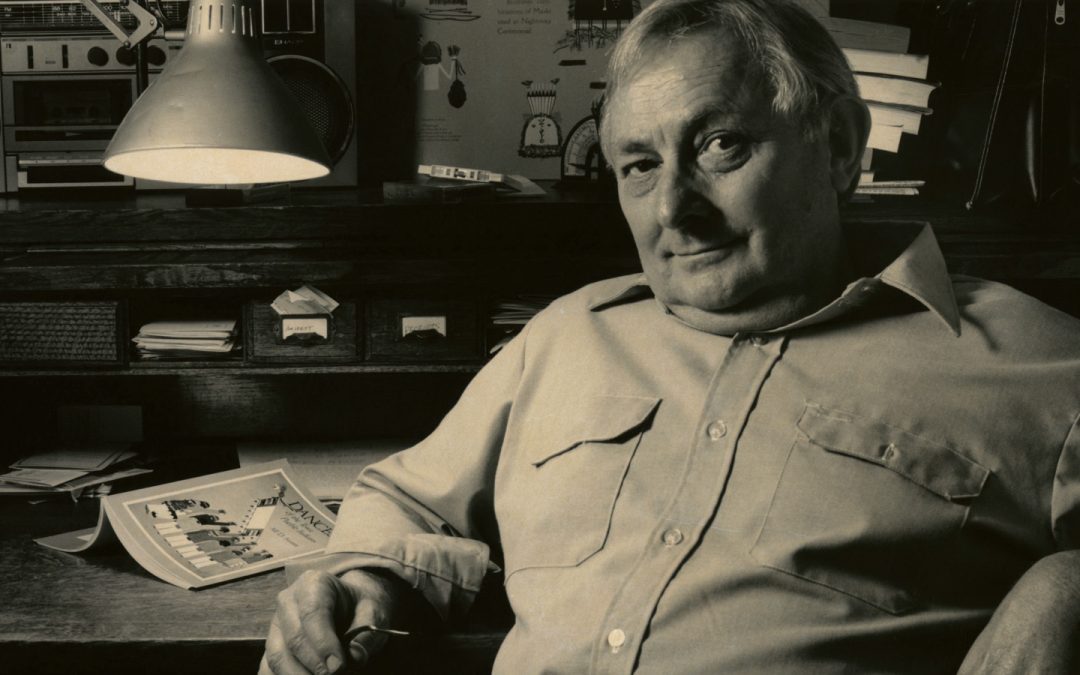

Tony Hillerman (’66 MA), who died in 2008, was a distinguished alumnus with an international reputation for his page-turning mystery series set in the Indian County of the Southwest. He was also a popular professor at UNM who taught a generation of students how to write.

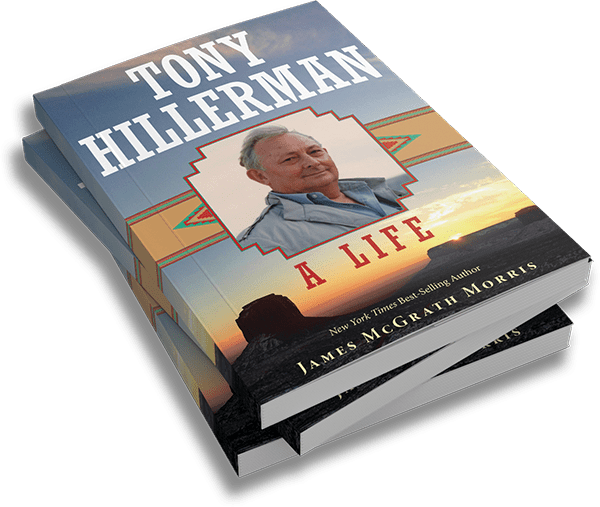

In a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM and the publisher, University of Oklahoma Press, allowed us to reprint it here.

The thermometer read ten degrees the morning Tony Hillerman drove to campus for the first day of the spring semester, January 5, 1970. He steered his dark-metallic-green 1970 Ford Maverick — the first new car he had ever owned — down Louisiana Boulevard to Interstate 40. When the smog above Albuquerque abated, the place offered Hillerman an expansive view westward. “It is exactly at this spot and at this moment that Mount Taylor comes into view,” he said. “It is my favorite mountain, and the gateway to my favorite places.”

To most commuters, the panoramic vista was just one more in a state filled with geographic splendor. But to Hillerman the view of the mountain now took on a meaning shaped by four years of studying Navajo culture. Tsoodził, as the Navajos called it, was one of the four sacred peaks delineating the boundaries of Dinétah, the Navajo homeland. To the north and west of Tsoodził lay the land that had served as the setting for the novel waiting to go to press in New York. “My map tells me the Turquoise Mountain is 62.7 miles from this noisy intersection,” said Hillerman. “In another sense the distance is infinite.”

The day would afford little opportunity to think about that distant land or his book. Students were streaming back onto the campus. Enrollment in the Journalism Department had grown by 20 percent during the last year. Hillerman had to prepare for three courses: Advanced Reporting, Newspaper Practice, and Media as a Social Force. In addition, he was planning for a new course in editorial writing in the fall and had tedious administrative responsibilities as department chair. His office was on the southern edge of the campus in one of the university’s ubiquitous adobe buildings that had once served as a residence for women students.

James McGrath Morris

Hillerman usually arrived on campus in an ebullient mood. “Have you seen the clouds today?” he would ask Mary Dudley, who worked briefly in the office. “If I didn’t give a convincing yes,” she recalled, “he would insist that we go out and we’d stand on the lawn of the Journalism Building and look at the clouds come over the Sandia Mountains.” Ever since he was a child growing up in Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl. Hillerman had been a cloud watcher.

When Hillerman had first begun teaching at UNM four years earlier, he had inherited the basic journalism classes such as News Writing. Instructing future journalists harkened him back to his days as a student at the University of Oklahoma after the war. “It was a wonderful time to be teaching,” said Hillerman. The students struck him as eager to learn and they took to his folksy pedagogy. The avuncular professor wore the narrow ties that were fashionable then, but loose with an open collar, with jackets and pants carelessly matched. “There’s none of the professorial moss about Tony,” noted a reporter who stopped by the campus that spring. “There is a disarmingly casual air about him.”

In class, students were treated to tales from the trenches of daily journalism. “He was always warm, humorous, generous, droll, with an anecdotal style of teaching, using lots of illuminating examples, many from his own experience,” according to former student Sharon Niederman, who became an author and journalist. Hillerman’s recollections were his tools of teaching, journalistic parables that also served to inspire. “We wanted to get out in the world and turn experience into prose,” said another former student, George Johnson.

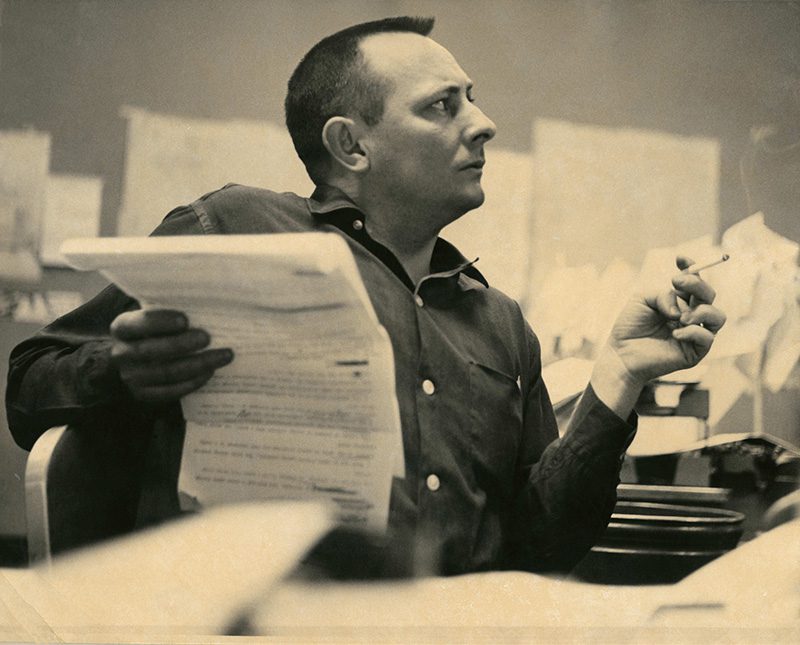

Like the much-admired Professor H. H. Herbert at the University of Oklahoma, Hillerman wanted his students to understand the power and the accompanying responsibilities that came with being a reporter. “From him, the students learned about real-life examples of proper journalism ethics,” recalled one student. Hillerman was not averse to using his own experiences to show the consequences, often unforeseen, of the news business. The topic was also on his mind in the 1970 spring semester. In his typewriter at home was the beginnings of a new novel in which journalistic ethics would play an important role.

Inspired by William Strunk Jr and E. B. White’s The Elements of Style, Hillerman offered a set of writing rules to guide the willing students. At home, he was putting them into practice in his fiction. “Writing is writing,” Hillerman told his students. “Whether fiction or non-fiction, poetry or prose, most of the same rules apply, most of the same devices are effective, most of the same flaws will kill you.”

Concision was paramount: “As sentences get shorter, they generally get stronger,” he said, paraphrasing the famous guide to writing. Active voice should be a habit: “It makes for forceful writing.” Concrete and specific nouns and verbs were preferable: A welder rather than a laborer, a begonia instead of a flower. Echoing the instructions to remove “cornstarch words” that Professor Grace Ray had given when he was in college, Hillerman offered his students a lesson in wordectomy. The sentence “The animals’ faces expressed pleasure as they consumed their food” became concise, concrete, specific, and active when written as “The hippos grinned as they chewed their carrots.” For Hillerman, writers were verbose because they lacked a command of the vocabulary. Conciseness does not demand short sentences, he said, “It requires simply that every word tell.”

The placement of words and clauses should be deliberate: “Use the phrase, or word, you wish to emphasize, at the end of the sentence or paragraph.” Also, a word or clause gains attention if used at the beginning of a sentence when it is not the expected subject. For instance, “Bad manners, she could never tolerate” or “Reckless drivers, these Armenians.” Writing with nouns and verbs achieved economy: the elderly man walked slowly by is made better by using the word plodded. “When you use adjectives choose them carefully,” he admonished. “If you pick the right noun or verb you probably won’t need them.”

Hillerman pushed his students to make their writing reveal rather than tell and to weave their material together. In his class on persuasive writing, aspiring journalist Susan Walton struggled at first with shedding the linear way she had been taught to write. “I wasn’t synthesizing well. I was really regurgitating,” she said. “And he wasn’t interested in that. He wanted to see a process of consideration and thought, coming out.” He pushed the students to use observations to develop a point of view. Drawing on his experience writing editorials at the Santa Fe New Mexican, Hillerman demonstrated his method. If, for instance, city maintenance was failing, Hillerman figuratively walked the reader down the street to the fence lined with trash, by the drain with cockroaches, and past the unfilled pothole. Now that he was a professor, he instructed his students to leave campus to hone their observation skills.

Compare the crowds at the airport and bus terminal, he told them. “If you think they represent different socio-economic classes, let me see enough to lead me to the same conclusion.” Visit bars frequented by homosexuals and a bar playing country-western music. “What do you see that identifies them?” Attend a trial and look for a bored member of the jury. “Show me what you saw that caused you to think that.” Hillerman argued observation and detail were the keys to a good journalistic story, according to one student. “Hone in on every detail so that you could set a stage around a story.” If the stories the students brought back were good enough, Hillerman offered them to the Albuquerque Journal, which occasionally published some.

Papers assigned are papers in need of a grade. When it came to the many essays and articles submitted by his students, Hillerman applied an idiosyncratic approach. He evaluated the students’ work on a ten-point scale and was not hesitant to provide an opinionated reaction, though gentle in his criticism and invariably encouraging. One of his talented students, George Johnson, broke up with this girlfriend just before the final assignment of the semester was due. “I was up late drinking beer and spewing out pages of typewritten angst, which I submitted the next morning.” Hillerman returned the work with an A+. “You write better drunk than most students do sober,” he wrote on the top of the paper. “That was all the encouragement I needed,” said Johnson, who went on to become a New York Times editor, science reporter, and author.

On major assignments students received lengthy typed evaluations. For instance, Hillerman wrote a one-page, single-spaced commentary praising and encouraging a young woman who had submitted chapters of a novel in a creative writing class he taught. “None of this has anything to do with the grade,” he wrote. He explained that she came to the class with a lot of talent and some bad habits and left with a lot of talent and some progress. “I rate that as Satisfactory Performance which earns you a C,” he concluded. “Had I been a better teacher for you it could have been a B at least.” To another student named Felipe, he wrote, “I think I will give you a B, which reflects a grade but not my judgment of your talent, which is remarkable.”

His dedication to his students prompted him to spend time selecting paragraphs from their work, typing them up on a stencil, and running them off on the office mimeograph machine. The blue-inked sheets were then distributed in class for group discussion. Typically, Hillerman Socratically pushed the students to apply his writing rules. “You say ‘obviously drunk,’” he might say, “What made it obvious?” Along with samples of their own work, Hillerman typed up more stencils with brief excerpts from the works of Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Gary Wills, Barbara Goldsmith, Ken Kesey, and Gay Talese, among others.

Hillerman was certain he could teach most of his students to write. “There are some who can’t be taught to write,” he admitted, “just as I can’t be taught to whistle thru my teeth.” He disliked many of the bromides about the craft. It was, for instance, “sheer nonsense” that writers write for themselves. “You have to write for someone otherwise you’re like a man at a telegraph key talking into a vacuum. It’s totally sterile and self-defeating,” said Hillerman. The point is to send and receive, “translating,” in his words, “the image inside your skull into symbols and launching it at a target.”

Teaching nonfiction while exploring the writing of fiction after-hours caused Hillerman to reflect considerably on the differences between the two. “The differences between fiction and non-fiction are more apparent than real,” he wrote. Nonfiction, which he had been trained to write and now taught, was less pliable than fiction and more craft-like. Fiction demanded more creativity resting on material either made up or from one’s memory. “The facts are crafted in your imagination,” Hillerman said. “They are glossy, persuasive, rich in symbolism, redolent of universal meaning, glittery, sordid, perfect, polished facts — the stuff of art.”

Despite the demands of being department chair and the late-evening hours consumed by his own writing, Hillerman always made time for students. He wanted to provide instruction on how to write but give encouragement as well, as Professor Morris Freedman had done for him. “He himself was an author, which impressed me,” said Hillerman, “and he saw promise in my work — which impressed me even more.”

Jim Belshaw was one of many aspiring journalists who experienced Hillerman’s devotion to students. After being discharged from the Air Force, Belshaw registered for classes at UNM in September 1970. The clerk handed him a small slip of paper with the name of his adviser. “I looked at the name and thought, well, I don’t know who Tony Hillerman is, but I know how to report.” When he reached Hillerman’s office, the professor looked over Belshaw’s test scores, particularly the ones for math. “Journalism, right?” asked Hillerman.

Hillerman guided Belshaw to an undergraduate degree in journalism and on to a career as a reporter and columnist. While working at one of his first jobs on a Las Cruces newspaper, Belshaw sent his former professor the manuscript of a book that had been rejected by a publisher. “The reason you sent it to me is because you lack confidence,” Hillerman wrote back. “Go to the library and pick any novel (not the great classics) and read it. You will find that you write as well as most, and better than some.”

Once Judy Redman stopped by his office. Hillerman was her adviser and she wanted to show him a creative writing paper on which she had earned an A. Another professor overheard the conversation and stuck his head in the door. He jocularly told Hillerman that students studying creative writing in the English Department will hurt their ability to do journalism. “I disagree,” replied Hillerman. “Good writing is good writing.” Redman went on to become a reporter and book author.

Hillerman, however, believed journalism was the best training ground. Carmella Padilla, a Santa Fe native, was uncertain what career she might want to pursue when Hillerman asked her about her goals. “I was thinking I wanted to be a physical therapist,” she recalled telling him, “but I don’t know, maybe I want to major in English.”

“Yeah, but what do you want to do?” persisted Hillerman.

“I want to write, I think.”

“Or do you want to teach?”

“Well, I think writing is more becoming to me than teaching.”

If that were the case, Hillerman advised her to stay clear of the English Department. He continued, according to Padilla, to say something to the effect: “If you really want to learn how to write, and learn the discipline of writing, which is what it’s all about, you’d be better off in the Journalism Department.”

“That really sunk in. I won’t be so bold as to say that Tony Hillerman directed me to be a journalist, but he certainly opened my eyes to that as an option. After completing the journalism program, Carmella Padilla became one of New Mexico’s most distinguished authors and an editor of work devoted to the Hispanic art, culture, and history of the state.

The dedication Hillerman showed his students, his willingness to guide them, and his irrepressible and engaging classroom storytelling made him an immensely popular professor. One student, however, ran up against a unique problem taking one of his classes. His daughter, Anne, made the mistake of enrolling in her father’s early-morning class. Her eyelids grew heavy and she dozed off to the sound of the voice that had once put her to sleep reading bedtime stories.

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

Read MoreUniversity of New Mexico alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca found peace in the written word…

Read MoreIn a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM…

Read MoreAmong campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, UNM has always been distinctly of New Mexico…

Read MoreYou can thank an alumnus for creating the image technology that keeps us connected…

Read MoreWhen I decided to attend UNM I applied to live on campus because I wanted to become involved in student life…

Read More

“UNM’s sense of place is unmistakable.”

V.B. Price (’62 BA) Author

“It takes more than the profile or outward appearance of its buildings to make a university, but if aesthetics mean anything in the intellectual development of students, and I feel certain that it does, then The University of New Mexico has an asset which gives it a unique position among the institutions of the nation.”

– Thomas L. Popejoy UNM president, 1948 – 1968

Unique and unmistakable, indeed. Among college campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, The University of New Mexico has always been distinctly of New Mexico. A visitor walking onto campus for the first time would never mistake her location for Seattle or Savannah, New Haven or Nebraska.

It wasn’t always so. In 1892, UNM was one building — a three-story red brick structure with a pitched gabled roof that would have looked at home anywhere back East. It was University President William G. Tight, who, as luck would have it, was a scholar of ancient Pueblo culture and a visionary, who began to build the campus that we know today. In 1908, he oversaw a remodel of what is now known as Hodgin Hall, adding beams, corbels and rounded stuccoed forms that are the unmistakable look and feel of adobe pueblos.

As Main Campus grew, each additional building adopted the same style — Spanish-Pueblo Revival — often at the hand of noted architect John Gaw Meem, who served as the campus architect from 1934 to 1956. In 1959, with the adoption of the Long-Range Campus Development Plan, the UNM Board of Regents agreed to preserve Pueblo Revival architectural style. The policy as it stands today reads:

“It is the policy of the University that all buildings constructed on the central campus continue to be designed in the Pueblo Revival style and that buildings on the north and south campuses reflect the general character of this style to the extent possible given the special needs for facilities in these areas.”

But form naturally follows function. And as the University has grown and education has become more technical, with laboratories, energy-saving and safety goals and many more students, staff and faculty, campus architecture has modernized. The goal is to preserve the original feel, not make new buildings larger cookie-cutter impersonations of the old.

“It’s a balance,” says Douglas Brown, chair of the Board of Regents. As he looks around Main Campus today, he is pleased to see new buildings in harmony with the old — not mimics but kinsfolk.

George Pearl Hall, the home of the College of Architecture & Planning along Central Avenue, is a striking example of ushering Pueblo Revival into the 21st century. The newest additions or major renovations on Main Campus pictured in these pages — Farris Engineering Center, which opened in late 2017; McKinnon Center for Management, which was completed in 2018; the Physics & Astronomy and Interdisciplinary Science building, or PAÍS, which was completed late last year; and Johnson Center, which opened this year — are undeniably modern but maintain common ancestry with the Meem style: flat roofs, low profiles, color-conforming stucco.

“I think it’s never looked better,” Brown says. Adaptation to the times even had the endorsement of Meem. “I get quite a bit of exhilaration when I visit the campus,” he said later in his life. “Sure, yes, they have all departed from the Pueblo Style, but people have to experiment a little bit. They have to have a little freedom to keep the campus alive. When you forbid these things, it starts dying.”

Do you know the feeling when you run into a friend you haven’t seen in a while and think, Wow, you’re looking great!

Maybe you’ve had the same feeling returning to UNM after months and months of COVID coop-up.

The campus is looking fabulous, with some stunning new buildings, some spectacular renovated spaces and meticulously groomed grounds.

If you can’t come to campus, we hope you enjoy the photos in these pages of some of the recent additions and renovations and a discussion of how a campus with an architectural identity so steeped in Pueblo Revival style is making its way into the 21st century.

Also inside we catch up with alumna Rachel Balkovec, who played catcher on the Lobos softball team in the 2000s and has made her way up the ladder of Major League Baseball. Since signing on with the New York Yankees, Balkovec’s career has resembled a hard-hit homer. She already had a number of “first woman” accolades before the most recent Big. League promotion: First female manager. Balkovec has been determined, patient and relentlessly upbeat, and we couldn’t be more proud to call her a Lobo.

At least two astute readers of Mirage readers caught an error in my letter in the Fall 2021 issue. In introducing the Q&A with alumna Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, I pointed to the historic nature of her appointment. And while it’s true that she is the first Native American to serve in the post, she is the third, not the second, New Mexican to do so.

The late Manuel Lujan, Jr., a New Mexico native, served from 1989 to 1993. But the secretary who slipped my mind was the quite unforgettable Albert B. Fall. Since we’re correcting the record here, how about a nice history lesson?

Fall, born in Kentucky and raised in Tennessee, settled in Las Cruces and became a teacher and lawyer and eventually a U.S. senator representing New Mexico. President Warren G. Harding putt Fall in charge of Interior in 1921 and just a year later Fall was charged with giving two of his friends valuable oil leases in land under his department’s control in exchange for bribes. The leases were in the Teapot Dome oil field in, Wyoming, which is why the scandal that drove Fall from government and into prison was called the Teapot Dome Scandal.

We’d very much like to hear your thoughts on the new website. You can email me at MirageEditor@unm.edu or alumni@unm.edu.

Stay safe and thanks for reading!

Leslie Linthicum

MirageEditor@unm.edu

There’s nothing quite as beautiful as UNM campuses in their Spring colors...

Those respiratory consequences can be dangerous — even life-threatening. But Matthew Campen, PhD, a professor in UNM’s College of Pharmacy, sees another hazard hidden in the smoke.

Thanks to a five-year, $3.7 million grant from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, a multi- disciplinary team led by Campen will investigate how inhaled smoke particles travel from the lungs to erode the blood-brain barrier.

Matthew Campen

In research published online in the journal Toxicological Sciences, Campen and colleagues report that inhaled microscopic particles from woodsmoke work their way into the bloodstream and reach the brain, and may put people at risk for neurological problems ranging from premature aging and various forms of dementia to depression and even psychosis.

“These are fires that are coming through small towns and they’re burning up cars and houses,” Campen says. Microplastics and metallic particles of iron, aluminum and magnesium are lofted into the sky, sometimes traveling thousands of miles.

In the research study conducted in 2020 at Laguna Pueblo, 41 miles west of Albuquerque and roughly 600 miles from the source of California fires, Campen and his team found that mice exposed to smoke-laden air for nearly three weeks under closely monitored conditions showed age-related changes in their brain tissue.

The findings highlight the hidden dangers of woodsmoke that might not be dense enough to trigger respiratory symptoms, Campen says.

As smoke rises higher in the atmosphere heavier particles fall out, he says. “It’s only these really small ultra-fine particles that travel a thousand miles to where we are. They’re more dangerous because the small particles get deeper into your lung and your lung has a harder time removing them as a result.”

When the particles burrow into lung tissue, it triggers the release of inflammatory immune molecules into the bloodstream, which carries them into the brain, where they start to degrade the blood-brain barrier, Campen says. That causes the brain’s own immune protection to kick in. “It looks like there’s a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier that’s mild, but it still triggers a response from the protective cells in the brain — astrocytes and microglia — to sheathe it off and protect the rest of the brain from the factors in the blood,” he says.

“Normally the microglia are supposed to be doing other things, like helping with learning and memory,” Campen adds.

The researchers found neurons showed metabolic changes suggesting that wildfire smoke exposure may add to the burden of aging-related impairments.

UNM's Jessica Richardson awarded grant to optimize treatment for the language disorder known as aphasia...

New and notable releases from Ray Windsor, Michael Malek Najjar, Hakim Bellamy, and other UNM alumni…

Recent Comments