Fall in New Mexico is a Treat for the Senses

With the arrival of autumn comes the smell of roasting chile, the sight of hot air balloons on the horizon...

While the Lottery Scholarship is aimed at recent high school graduates, the Opportunity Scholarship is intended to help returning students or older adults who didn’t make it college after high school graduation and those who attend part-time.

UNM adds to the mix the Lobo First-Year Promise, which supports first-year students whose family income is $50,000 or less with full tuition and fees.

As anyone who has tallied up a grocery bill or filled their gas tank or tried to buy a house or rent an apartment lately can appreciate, these assistance programs can change the game for New Mexicans trying to take the step to a better future through a bachelor’s or associates degree or a specialized certificate in this blisteringly hot economy.

The importance of access to higher learning for everyone might come into clearer focus as you read the alumni profiles in this issue of Mirage. It certainly did for me as I put this issue together. There are millions of Americans and plenty of New Mexicans who live productive, interesting and meaningful lives without ever having taken a seat in a college classroom. But for many others, their first steps toward greatness happen on the way to a degree.

I’m thinking of Jack Dongarra, an Italian kid from Chicago whose parents never finished high school. He had dyslexia but he was pretty good at math so he went to college as a math major. Many years and a PhD from UNM later, Dongarra just won the $1 million Turing Award, considered the Nobel of computer science.

I’m thinking of professional mountain biker Doug Campbell, who decided to get serious at 26 and enrolled in UNM’s College of Engineering without much thought about what he wanted to do with his life. Today he’s CEO of a company producing a smaller, cheaper alternative to traditional lithium-ion electric car batteries. If you buy a Ford or BMW EV five years from, money is on Campbell’s battery cell powering your ride.

I’m thinking of UNM music major Raven Chacon from Ft. Defiance, Ariz., whose unique tonal compositions were just recognized with the Pulitzer Prize for music. And of Cynthia Chavez Lamar, whose PhD at UNM in American Studies helped focus her thoughts on collaboration between museums and Indigenous communities and who now heads the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian.

I could go on — we have a remarkably strong lineup of alumni in this issue.

But I think you’ll want to read about them yourselves.

And who knows which student taking a first class this Fall, thanks to the promise of free tuition, might be the next UNM grad to make the big discovery or reach the top of their field?

Leslie Linthicum

MirageEditor@unm.edu

With the arrival of autumn comes the smell of roasting chile, the sight of hot air balloons on the horizon...

UNM grad helps spark electric vehicle revolution…

Read MoreOpera singer pivots to performance coaching…

Read MoreAlumnus caps computing career with prestigious prize…

Read MoreAlumna heads up museum devoted to the American Indian experience…

Read MoreAlumni board president keeps UNM ties tight…

Read MoreAlumni take home a Grammy and a Pulitzer for music…

Read More

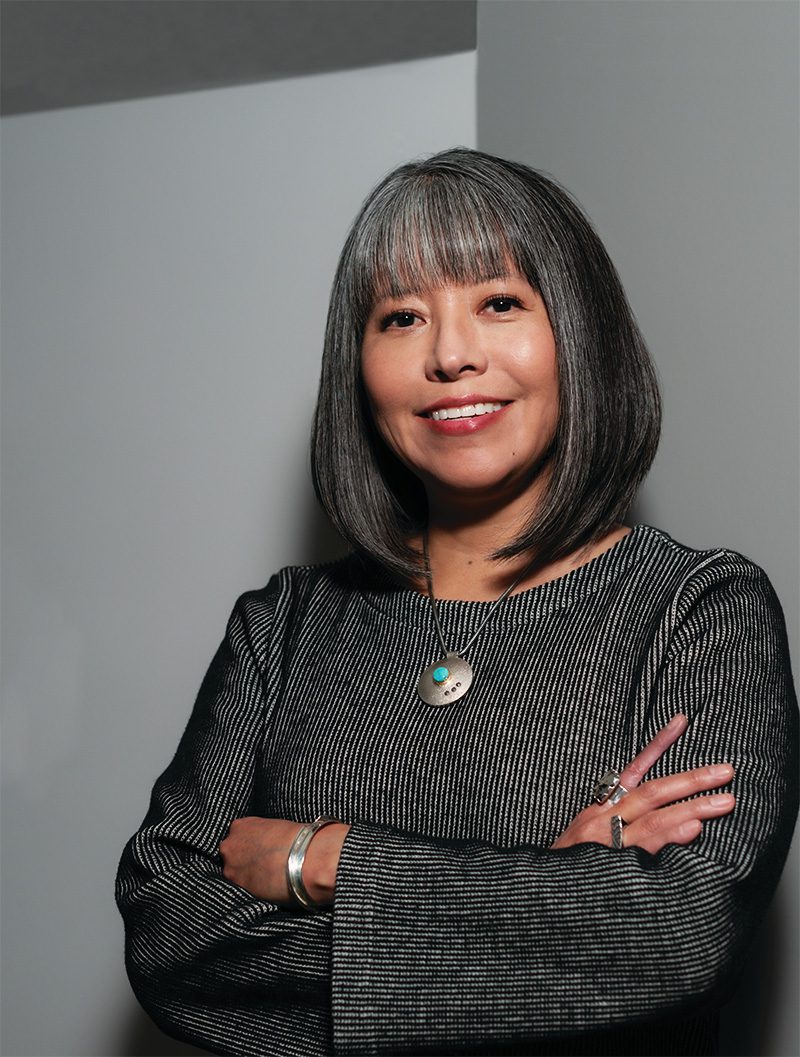

Photo: Walter Lamar

by Mirage Staff

Cynthia Chavez Lamar (’01 PhD), the new director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, was born in Dallas, where her family was living under the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Voluntary Relocation Program. While her father trained as an architectural draftsman, the young family missed home — San Felipe Pueblo along the Rio Grande in New Mexico. The Chavez family — father Richard of San Felipe, mother Sharon who is Hopi, Navajo and Tewa, and three children — put their roots back down in San Felipe, where Cynthia excelled in school, graduated as valedictorian of Bernalillo High School and went on to study art at Colorado College.

Her grounding in Pueblo culture and tradition help to guide her in her new role as the first Native American woman to lead the National Museum of the American Indian’s museum system. And she credits her PhD in American Studies from UNM in 2001 with helping her to learn the importance of collaboration with tribes in curating museum exhibitions.

Mirage talked to Chavez Lamar about the National Museum of the American Indian, her time at UNM and best practices for getting New Mexico chile and salsa back to D.C. in her luggage. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Cynthia Chavez Lamar

Mirage: Tell me about your childhood.

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: I grew up in San Felipe and went to school there too, so it was really an important part of my upbringing, being in the community and being part of the community. That really forms a strong basis for my identity. My dad made heishi (beads) and is also a self-taught jeweler. He has become a master of lapidary work. Both of my parents stressed education a lot and my mom, since we were very little, used to read to us every night. We grew up with a love of reading. I was a good student. I knew that it was important to my family and to my future that I do my best in school. So I tried really hard and did well.

Mirage: Then you went to Colorado College and majored in studio art. How did you find CC?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: That’s a funny story. My dad being a jeweler, he participated in these exclusive small tours in the summers to see artists at home. So they would come to our house and my mom would have a great lunch for them and they would get to talk to my dad about his jewelry. In this one group there was a Dartmouth recruiter and he started talking to me about Dartmouth and was encouraging me to apply to Dartmouth. And I told him, “That’s too far from New Mexico; I really want to be closer to home.” And he said, “Well, I know this great small liberal arts college in Colorado called Colorado College. You might want to check it out.” I always tell people at Colorado College I was recruited to CC by a Dartmouth recruiter.

Mirage: And you majored in studio art?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: Growing up around art and artists, it was a big part of my life and upbringing. My mom from her Hopi/Tewa side knew how to do traditional clay pottery, so she taught us to work with clay. I would make all kinds of different figures. When I went to college it just seemed like something that was just part of me and it seemed natural to go that route. At CC I did printmaking and photography. I enjoyed it, but I’ve always been a practical person, so I knew by my junior year that I wasn’t strong enough in any of those and I knew that if I was going to pursue the path of being an artist it certainly would be a struggle and it would take a long time. And I thought, “I’m really going to need a paying job,” so I decided to go to grad school. I had to think about, “What is it I’m interested in? I’m definitely interested in American Indian subject matter because of my background, because of who I am.” At the time there were only two master’s programs in American Indian studies, and I decided

to go to UCLA.

Mirage: What was your path into museum work?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: When I was at UCLA I had the opportunity to work with a guest curator who was doing a show on Hopi kachina dolls for the UCLA Fowler Museum. That experience involved some fieldwork — a lot of research — and introduced me to the curatorial process and I really liked that. It allowed me to still be involved with Native art, it allowed me to use my intellect, it allowed me to explore new subjects. To me, it was a creative process in its own way. That’s when the bug bit me. And I thought I needed to get my PhD if I want to be a curator, so that’s why I ended up at UNM.

With her parents Richard and Sharon Chavez in 2004 during the grand opening of the National Museum of the American Indian.

Mirage: Was that about coming home? The strength of the program?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: UNM had the only PhD program where you could specialize in Native American art history. And it also was about coming home. I had a bit of a hiccup on my master’s thesis because once my dad found out the topic I was working on, he said, “You can’t do that.” It was a cultural issue. When I was at UCLA, I started looking at issues around representation, especially when it comes to American Indian culture. Throughout history, sacred and ceremonial items have often been on display in museum exhibitions. I was looking carefully at that history and that was what my master’s thesis was going to be about. My dad’s concern was that at our pueblo, given your position in the community, there are only certain things that you should know or you should acknowledge you know. If you’re a woman, like me, and you’re not initiated into any societies or groups and don’t live in the community, you’re probably a person who is considered to have very little knowledge of certain things.

By looking at the display of sacred and ceremonial items in exhibitions, I think he was concerned that I would start getting into the details of what those things were, and as a Pueblo person you always have to be mindful that what you do outside your community can impact your family. That really put me into personal turmoil, because I questioned who I was as a San Felipe Pueblo person. I thought, “Have I really forgotten who I am?” It was kind of traumatic, honestly. But professionally it made me think about how can I still address this as an issue, because it is an issue. We need to let museums and non-Native people know that to have sacred and ceremonial items on display is problematic. With my PhD I looked at the history of anthropology and how in the past anthropologists were always digging and trying to get information out of Pueblo people about secret or sacred information and what that resulted in. That was my way to address something that I thought was important to address but stay true to who I am as a Pueblo person.

Mirage: At UNM were there any particular mentors?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: The person that had the most impact on me was Dr. Mari Lyn Salvador, who is no longer with us. She was in the Anthropology Department and her scholarly practice was one that centered on collaboration. That’s really when I got introduced to the idea that in curating an exhibition, you can collaborate with artists and with Indigenous community members.

Mirage: That brings me to the question of your museum now and importance of collaboration with the communities who you are putting on display. Your museum feels different from other museums. Can you explain that?

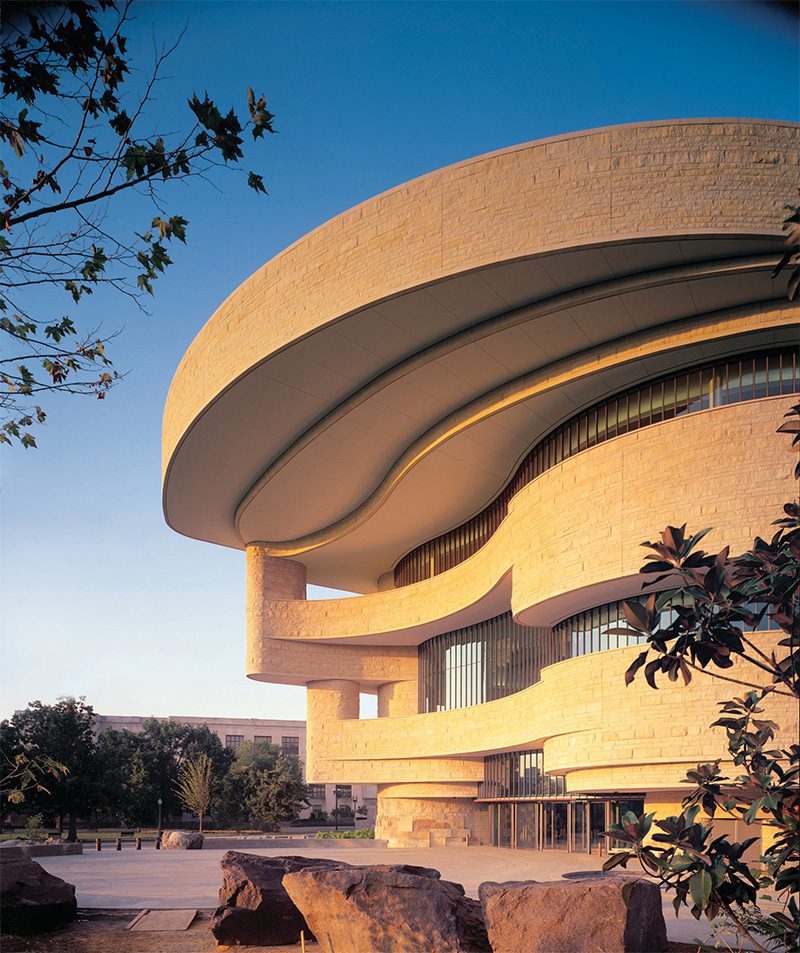

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: The museum’s origins were really based on collaboration and advocacy from Native Indigenous peoples. A lot of collaboration was done with Indigenous people to establish exhibitions, to develop the architectural concepts of the museum on the Mall and the Cultural Resources Center in Suitland, Md. The museum’s origins are based on Native Indigenous values and beliefs and concepts. That’s like our foundation that sustains us. That spirit is there and it will never go away, because that’s how NMAI was born.

Mirage: It’s a big responsibility. How are you feeling about the job?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: It’s definitely a lot of responsibility, but it’s also something I know I don’t have to do alone. Thankfully there’s a tremendous staff in place and they’re the ones that make the museum operate on a day-to-day basis. So I have a tremendous amount of gratitude for them and the work that they do. I think it’s going to take me about a year to sort of settle and to feel like I have both feet on the ground. I’m still in the stage of learning something new every day. We’re strong now. But I think my challenge is trying to find that time to think about some bigger initiatives that the museum needs to take on to become even stronger.

Mirage: When you have challenges, what is your support system?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: For me, family is really important. I have a great husband, (former BIA law enforcement deputy director) Walter Lamar. He’s a tremendous person in Indian Country. And thankfully I still have both my parents. They’re always there for me. And my brother and my sister are also there for me. I do rely on family to help me get through challenging times.

Mirage: How often do you get back to New Mexico?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: Before the pandemic I’d get back four to six times a year — work and personal visits. I’m hoping as travel is opening up and I’m getting more comfortable traveling again that I’ll be able to get back to New Mexico at least that much again. I was actually just there for our May 1 feast day. We had it after two years of not having it. We were all very excited but also a little bit nervous. It went well and it wasn’t crazy busy, so I actually had time to sit for a bit and watch the dances. One of the things that I’ve really missed over the course of the pandemic was hearing the songs and seeing the dances. You don’t realize how much you miss something until it’s not there. That was really comforting to me and much needed.

Mirage: What food is the Chavez home famous for on feast days?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: There’s two things that people always ask us to make and it’s spinach casserole, which is interesting, and cheesecake.

Mirage: How do you get New Mexico food in D.C.?

Cynthia Chavez Lamar: I get things through the mail sometimes. My mom overnights me some things. And when I go home, I usually pack my suitcase. Now at the Albuquerque airport they sell the frozen red and green Bueno post-security, so I’ll sometimes bring a small cooler with me and fill it up and bring it home. I had lunch with Deb Haaland (U.S. Secretary of the Interior and fellow UNM alumna) about a month ago and I wanted to bring her something so my gift to her was a jar of Sadie’s Not As Hot salsa.

The National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Taking a novel approach to understanding climate change, Paul Hooper, adjunct associate professor of Anthropology, dived into existing data sets that contain historical information about societies, including measures of complexity in language, government and economies. He reanalyzed that information to look at how societies fared during cooling periods.

“I found that societies were substantially less complex during the coldest centuries of these climate events. For societies in northern regions, cooling was associated with a loss of about 300 years of accumulated social complexity,” Hooper said. “The research shows that the success of civilizations depends on favorable climatic conditions.”

While Hooper focuses on cooling, not warming, his analysis published in Cliodynamics: The Journal of Quantitative History and Cultural Evolution illuminates yet another potential disruption of changing climate.

“Societies based on agriculture, like our own, are productive within a surprisingly narrow range of climatic conditions,” Hooper said. “Too cold, too hot, or too little water, and productivity suffers. Complex societies have never faced the climate conditions that are now on the horizon, and they’re going to be a shock to our social and economic systems. In addition to higher temperature, precipitation will also be key. While some areas will dry up, others will receive more water due to higher rates of evaporation from the oceans.”

UNM archaeologist and Prof. Keith Prufer co-led a team excavating a site in Belize...

Photo Credit: Roberto E. Rosales (’96 BFA, ’14 MA)

Alumni board president keeps UNM ties tight

By Leslie Linthicum

Amy Miller’s UNM cred goes well beyond her two academic degrees — a B.A. in Journalism and Sociology in 1985 and a Master of Public Administration in 1993.

First, let’s look at her family tree. Miller’s dad, James P. Miller Sr., received his PhD from UNM and taught in the College of Education. While dad was getting his doctorate, her mom, Millie, worked in administration in the Department of Geology.

Miller’s brother, James P. Miller Jr., is a two-time UNM graduate with his B.A. and PhD. Her sister, Susan Lester, has a B.A. from UNM. Miller’s sister, Linda Miller, diverged from the family tradition and got her degrees from NMSU but worked at UNM in Computer and Information Resources and Technology.

Miller’s husband, Cliff McNary, got his B.A. at UNM in 1986 and his M.A. in 1994.

The McNary/Miller children are also Lobos. Daughter Kiera received a bachelor’s in chemistry in 2019 and a master’s in nanosciences and microsystems engineering in 2021. And son Thailen just graduated with a B.S. in psychology. Amy’s nephew Kavi Miller graduated with a B.A. in business in 2020 and niece Zunyi Miller graduated with her business degree in May alongside Thailen.

In 1995, her father received one of the first Zia Awards given by the Alumni Association

to honor outstanding alumni who live in New Mexico. In 2016, brother Jim received

the same award.

Miller, 59, the incoming president of the UNM Alumni Association, takes obvious delight in drawing the map of her ties to Loboland.

“I have deep roots,” she says with a laugh.

Miller joined the Alumni Association board in 2017 and she has spent the past two years working on board development, particularly in strengthening the board by encouraging more diversity and active commitment among members.

“We want the board to look like the state,” Miller says. “And we want board members to be engaged in being great ambassadors for UNM.”

Miller wants to continue that work as president, to work on ramping up in-person alumni events that have been curtailed during the pandemic and to also support the career mentoring efforts spearheaded by the previous two presidents, Michael Silva and Chad Cooper. Silva and Cooper, both African American men who served during two years of unrest and activism — and spurred by the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police —brought their activism to the role of president.

Miller intends to allow her own passions — environmental sustainability, social justice and access to education — to guide her term.

“Maybe it’s a function of age, but I am not going to sit silently,” Miller says. “I am focused on living and breathing my values.”

• Miller lives in a house near North Campus that was the original location of Animal Humane Association of New Mexico.

• Since she graduated, Miller has never lived more than two miles from Main Campus.

• Miller and McNary’s two children came into their family via adoption from South Korea.

• Miller’s fur babies are cattle dog Baby and Boxer/Pointer cross George.

• While an undergrad, Miller played in the UNM flute choir.

One of Miller’s early values was education. Her father was a school administrator in Anthony, N.M. on the southern border. He moved the family to Albuquerque in 1971 to pursue a PhD and young Amy explored the campus in the afternoons after school let out.

After her father completed his doctorate, the family moved to Santa Fe, where her father served as superintendent of schools.

When 1981 came around and Miller was a 17-year-old high school graduate without much direction, she listened to her father’s advice.

“My dad really wanted me to go to UNM,” Miller says. “He believed very strongly that this university changed his life and the life of our family.”

So, she moved into Alvarado Hall.

“I was pretty fuzzy-headed,” Miller says. “My first year was a little tough.”

She had no idea what she wanted to do with her life and adjusting from small-town Santa Fe to big-city Albuquerque was a challenge.

In her second year, she got involved in modern dance and music, where she found her people. She was also a good writer; in high school she had worked as an intern at the Santa Fe New Mexican newspaper, running copy in the frantic days when inmates took over the New Mexico Penitentiary. She took some journalism classes at UNM and found her major.

“I just like talking to people and hearing their experiences,” Miller says.

Her first job was technical editing, then she moved into communications and marketing with the state’s credit unions and rural electric coops. During that time, Miller was involved in a serious motorcycle accident on Central Avenue in front of UNM and spent months undergoing surgeries and physical rehabilitation.

One day, when she was learning how to walk again, she took a stroll through campus and saw a flyer for the Master of Public Administration degree program. She enrolled in graduate school, started dating and married her husband (whom she met during their undergrad years) and found another lifelong passion.

“I have a love for politics and public policy,” Miller says. At PNM, the electric company where she worked for 15 years, Miller was able to combine her skills in communication and government affairs.

In 2017, PNM initiated deep layoffs and Miller lost her job.

“I wasn’t expecting it and it hit me pretty hard,” she says.

One day over some wine, a friend suggested Miller start her own company. It wasn’t anything she had ever envisioned, but the more she thought about it the more she realized it was an opportunity to do the kind of work that mattered to her. She opened AMM Consulting and developed a portfolio of clients in renewable energy and clean transportation among other passion projects, including the MAS charter school.

“I decided I would do work that fulfills me,” Miller said. With her two children now being UNM graduates themselves, Miller has been reflecting on the meaning of a UNM degree.

“We have trouble taking pride in our state,” Miller says. “What comes to mind when I think of UNM is that idea of — ‘you’re just going to UNM’? I think we have to change that thinking to, ‘no, UNM is a damned good university’. There are really good people teaching here. There are people doing life-changing work here. We have to take more pride.”

Laura Crossey and Karl Karlstrom, both professors in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, joined an international team of scientists on an expedition to the Tibetan Plateau, driving thousands of miles across Tibet to sample bubbling hot springs to learn more about how the Earth’s underground system of geological plates move and collide.

Their findings were published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal. Crossey was one of the authors.

The team sampled gasses emitted by geothermal hot springs to ascertain how plates have moved deep underground. Where the crust is thick, mantle-derived helium cannot escape. Where plates have shifted an dropped away, the gas escapes. The team was able to define a 1,000-kilometer-long East-West boundary in southern Tibet where what is known as the Indian plate has dropped away from the Himalayan plate.

The findings add to our knowledge of the Earth’s mantle and also have practical implications.

“Additionally, these forces also generate some of the most powerful and deadly earthquakes on Earth,” Crossey said. “Understanding the detailed nature of the colliding plates can help us better prepare and plan for earthquakes.”

UNM archaeologist and Prof. Keith Prufer co-led a team excavating a site in Belize...

Recent Comments