In A Solid State

UNM grad helps spark electric vehicle revolution…

Read More

Photos:

Roberto E. Rosales (’96 BFA, ’14 MA)

UNM grad helps spark electric vehicle revolution

By Leslie Linthicum

When Doug Campbell was a skater punk in Albuquerque in the 1980s, The University of New Mexico campus was his skate park. Unfocused in school and happy to buck authority, he rode the ramps and sidewalks of campus, one step ahead of the university police.

Campbell went on to earn two degrees from UNM, a bachelor’s in civil engineering in 2001 and master’s a year later, and took several classes from Gerald May, who happened to have been the president of UNM when Campbell was getting chased off campus by UNM police.

Well, no hard feelings on either side.

Campbell had finished his bachelor’s and was unenthused about the traditional career paths for a civil engineer. As Campbell’s undergraduate advisor, May saw a saw a young man struggling to figure out his future.

“He was one of those students who was driven, exceptionally bright. He was focused,” May says. “And he was restless, in the sense of wanting to do more.”

“Doug,” May told him, “you’re destined for great things, but if you can’t decide what you want to be, go to graduate school and you’ll better see your path.”

“And,” May says today, “he did.”

In graduate school, Campbell found his passion in aerospace and in solving complex problems.

Today, he is an entrepreneur who sold an aerospace startup two years ago and is CEO of a next-generation battery company that has deals with Ford and BMW.

Blessed by his success, Campbell just donated $5 million to the School of Engineering, earmarked for the Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering. The gift is without restrictions except for one: The department will be named for May.

When he made the gift and specified the department be named for May, Campbell wanted to honor a man who helped change his life.

“He is such a phenomenal individual,” Campbell says. “He was such a humble and phenomenal teacher. I just developed an immense amount of respect for him.”

Campbell, who splits his time between Longmont, on the Colorado Front Range, and Gunnison, on Colorado’s Western Slope, has arrived in Albuquerque to look for an apartment for his eldest son, Ethan, who begins UNM as a transfer student this year. He drove down from Boulder County in his Porsche Taycan, a sleek rocket of an EV that can get to 60 in three and a half seconds. “Amazing,” is Campbell’s assessment of his electric ride.

Not yet 50 and with a startup cash-out behind him and another one in the high-stakes and lucrative race for the best EV battery technology, Campbell could be one of those arrogant Silicon Valley tech bros he likes to call an unprintable name.

Instead, he’s casual and funny, ready to tell an embarrassing story on himself (his personal website is www.entrepreneurialdysfunction.com and he describes himself as a battery nerd) and just as ready to admit to the luck that’s got him to where he is today.

“There’s always luck,” Campbell says. “But I also saw that we as a society are moving toward an electrified future.”

Campbell’s parents met at St. Pius High School in Albuquerque and Campbell was born in Mountain View, Calif., where his father was stationed in the Navy. His mother, Mary, was 18 when she gave birth and shortly after found herself divorced and back in Albuquerque.

Until she married Campbell’s stepdad when he was 10, “She was a single mom and basically said, ‘I gotta do something with my life,’” Campbell recalls. “And she went to UNM and got a degree in civil engineering. I grew up on campus. I would putz around and go to the

Duck Pond. She would take me to school and say, ‘I gotta go to class; entertain yourself.’”

His mother, who died in 2006, was one of the reasons Campbell chose to study engineering when he finally enrolled in UNM in his mid 20s.

His path to college was anything but traditional and that has a lot to do with hormones.

“Pre-puberty Doug was very active, very athletic,” Campbell says. “Post-puberty Doug was a shitshow. Always in trouble. Causing hell. Very anti-authority.”

Campbell barely got through Albuquerque High School and didn’t even consider going to college. Luckily, he found the sport of mountain biking and managed to get very good at it.

He turned pro in 1997 and spent the remainder of the decade racing all over the country on the national circuit. As he focused and matured, Campbell started taking some courses at what is now Central New Mexico Community College. His last full-time racing season was 1999, when Campbell, then 26, realized he needed a second act.

He enrolled at UNM as nearly a junior thanks to his CNM credits and chose engineering because he didn’t know what he wanted to do and it was the family business. Campbell raced through his undergraduate degree, finishing in 2001 just in time to realize that designing bridges and roads and sewage plants wasn’t his thing.

With May’s advice to keep searching for his niche in grad school, Campbell connected with Prof. Arup Maji, who was doing research on materials for spacecraft components and space structures and was associated with the Air Force Research Laboratory. Campbell found an area of engineering that excited him and he finished his master’s degree in a year, spending most of his time working in the Space Structures Group at the research lab.

“He was always a top student,” says Maji, who funded Campbell’s master’s work and chaired his thesis committee.” When Campbell graduated, May wrote some letters of recommendation.

“This young man is destined for something exceptional,” he wrote. “Whatever he is going to set out to do he will accomplish.”

Campbell, with his wife, nurse Arishanda Campbell (‘00 BSN), left for the mountains of Colorado and worked in design and program development for a company that creates composite materials for harsh environments and another R&D company that had battery technology in its portfolio.

Frustrated with management, Campbell broke out on his own in 2012 and co-founded ROCCOR, a space deployables and small satellite component products company that started as the prototypical two guys in a garage and after some lean years grew to employ dozens and develop technology to remove some of the millions of pieces of debris in space.

Simultaneously, Campbell co-founded Solid Power in 2012, as a spinoff from the University of Colorado Boulder. In just 10 years, Solid Power has designed and is producing a different kind of battery for the electric vehicle market.

Since he stepped down as CEO at ROCCOR in 2018 and sold the company in 2020, Solid Power is his only focus and the company is closing in on mass-market production of its battery cell.

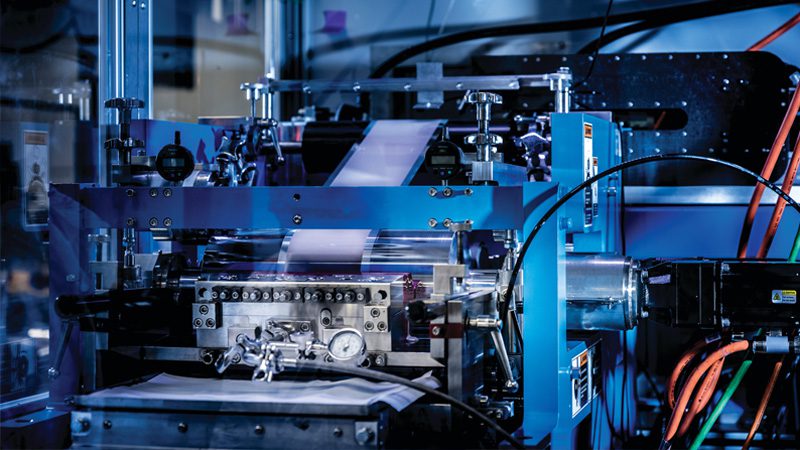

Thin layers of a sulfide-based electrolyte bound for battery cells on the production line at Solid Power.

Ask Campbell to explain his product and the engineer in him takes pen to paper and draws it out.

Chargeable lithium-ion batteries store energy by drawing ions from the cathode (plus) side to the anode (negative) side through a porous separator encased in a liquid electrolyte. They produce power by reversing that process and releasing electrons. That system has four components: the cathode and anode, electrolyte liquid and a polymer separator.

It is the kind of battery that currently powers the EVs on the road today.

An all-solid-state battery uses the same cathode/anode system but replaces the electrolyte liquid and polymer separator with a single component called an electrolyte separator.

“It is a discreet solid layer,” Campbell says, “so think Oreo cookie: creamy filling and your two little sandwiches.”

By replacing the two components with one solid state package that is more energy-dense, the vehicle’s range can increase by 30 to 50 percent, Campbell says. And because an all-solid-state battery is stable across a wide temperature range, auto manufacturers may be able to eliminate the costly cooling technology they build into electric vehicles.

“At the end of the day this works to deliver higher range and lower cost. That’s why Ford and BMW are working with us,” he says.

The proprietary component that Solid Power is delivering to Ford and BMW is the electrolyte separator.

“Broadly it’s a sulfide-based electrolyte,” Campbell says. Solid Power synthesizes the electrolyte as a powder, then turns it into a slurry (think cake batter), which is pumped into a machine similar to a printing press that pumps out thin layers that are stacked into a cell about the size of an iPad; a process very similar to how today’s lithium-ion batteries are produced.

The company is in pilot production, making hundreds per week.

Solid Power provides only the cells to the automakers, who design the battery packs. Campbell estimates his cells will be in EV models as soon as 2027.

His path from mountain biker to successful entrepreneur with millions to donate to his alma mater can look like a head scratcher. But Campbell sees it all as a perfect arc.

“I have over-the-top ambition. It’s how I’m wired. I’m always go, go, go, go, go. I’m just driven,” Campbell says. “And I’d argue that cycling primed me for business.”

Training all the time, watching your eating, weight and sleep and knowing that not winning a race isn’t failure are fundamentals for an endurance athlete.

“You can’t worry about yesterday’s results, you’ve just got to just train, train, train,” Campbell says. “And that’s the same thing in business. You have to be persistent. You have to ride the highs and the lows. You can’t get too excited in the highs and you can’t get too bummed out in the lows. Otherwise, you’ll drive yourself crazy and you’ll flame out.”

Maji, the engineering professor who funded Campbell’s graduate work, is surprised by the speed and level of Campbell’s success, but not that he’s made it big.

“I’m not surprised in the context of his personality and caliber and zeal to do something different,” Maji says. “He was always a top student. And looking back, I can see why, given the traits that he had, he could certainly blossom into a very successful entrepreneur.”

When Campbell made the gift and specified the department be named for May, Campbell wanted to honor a man who helped change his life.

“I’m greatly honored,” says May, who retired from UNM in 2002 and is 81. “I see a young man who has accomplished extraordinary success at a young age. Quite exceptional. And I think it’s exceptional at this young age that he’s looking to benefit his school.”

Campbell readily admits he is not Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates or Elon Musk. “Five million sounds like a lot, but at the end of the day it’s not,” he says.

So he wanted his gift to be targeted to a small corner of the world that means something to him.

“It’s always been Albuquerque,” Campbell says. “Because even though I don’t live here I’ve always had a passion for this place. Because there’s goodness here. New Mexicans are good people. They’re very down-to-earth people. And UNM is competing with phenomenal research institutions, and I do think it punches above its weight, but it’s located in a relatively small state. I want to make my little corner of the world — the civil engineering department — more competitive.”

Campbell hopes his gift, which will endow a fund to be used at the discretion of the the Civil Engineering Department chair, will help to sweeten the pot to attract and retain world-class faculty.

Part of the plan is to help UNM compete with larger, better-funded universities in the competitive world of startups and spinoffs, a passion close to Campbell’s heart.

“I’m an Albuquerque kid who’s now running a company that the business community pits against spinoffs from Stanford and MIT,” Campbell says. “I’m not intimidated by anybody who comes out of these blue-chip universities.”

UNM grad helps spark electric vehicle revolution…

Read MoreOpera singer pivots to performance coaching…

Read MoreAlumnus caps computing career with prestigious prize…

Read MoreAlumna heads up museum devoted to the American Indian experience…

Read MoreAlumni board president keeps UNM ties tight…

Read MoreAlumni take home a Grammy and a Pulitzer for music…

Read More

Photos:

Roberto E. Rosales (’96 BFA, ’14 MA)

Opera singer pivots to performance coaching

By Amanda Gardner

Performing on some of the biggest stages in Europe and the United States, soprano Ingela Onstad has felt the highs and lows of being a performer.

The highs: Singing at the Santa Fe Opera and Dresden’s Staatsoperett and mastering a piece for Mahler’s Fourth Symphony in just one night so she could fill in for a sick cast member. The lows: Shaking hands, knees and voice and forgotten lyrics.

Now Onstad (’14 MM, ’17 MA) takes her training and experience to a new venue, an Albuquerque-based coaching business called Courageous Artistry, which helps others overcome stage fright, build confidence and achieve career goals.

When Onstad first hung out her shingle (a largely virtual shingle thanks to the pandemic), she catered primarily to other singers and performers, but has now expanded her clientele to include instrumentalists and even professional football referees.

“I can help all humans with these skills. It’s pertinent to people’s lives,” says Onstad, who holds master’s degrees in both voice performance and mental health counseling from UNM and counts some 15 to 25 coaching clients, most of them in North America (including Canada) and Europe.

Most of the issues come down to the basic human emotion of fear.

“Fear is deeply woven into our biology,” Onstad explains. “Fear of judgment, fear of criticism.”

Coaching usually starts with cognitive work on how the brain works, the biological fundamentals of fear. “Our natural factory setting is a lot of negative thoughts,” she says. “We assess whether that is helpful or harmful.”

Once her clients understand this basis of fear she then helps them outline their goals, and then moves forward using various cognitive and emotional tools.

Nikki Kelder, an actress and singer in New York City, came to Onstad in November 2020 for help dealing with “extreme anxiety” in auditions and self-sabotaging. Through visualization, breathing techniques, goal setting, books, worksheets, podcasts and more, Kelder has learned to identify how she undercuts herself so she can show up better in auditions. “I began to feel more hopeful and positive about the audition process,” she says.

Onstad herself has been auditioning since she was a preteen in Santa Fe. Because few young people were studying voice in Santa Fe at the time, she stood out, something which helped build her confidence from the beginning. “I was a big fish,” she remembers. “I was one of the best ones around.”

She continued to perform in junior high and high school, started singing professionally when she was 18 and then moved on to ever bigger ponds. She was accepted into the renowned voice program at McGill University in Montreal where she was among many fellow students who went on to build international reputations. She recalls her “jaw hitting the floor” when she listened to master’s and doctoral students sing during weekly studio sessions.

From there, Onstad moved to even bigger stages, this time in Germany. Had she stayed in the U.S., she likely would have had to operate as a freelancer (much like Kelder). In Europe, vocal artists are hired by certain opera houses, with contracts lasting a number of years. Over the span of about a decade, Onstad worked at opera houses in three different cities.

In Europe, she performed opera at Dresden’s Staatsoperette, Oldenburgisches Staatstheater and Landestheater Schleswig-Holstein. In the U.S., she has sung at the Santa Fe Opera and has had concert performances with the Santa Fe Symphony, New Mexico Philharmonic, Chatter, Bad Reichenhaller Philharmonie, Chicago Arts Orchestra and many others.

Because she is a lyric soprano, Onstad often sang (and still sometimes sings) the lighter roles in operas. Think more Mozart and Puccini, less Wagner. She has played Musetta in one of her favorite operas, Puccini’s La Boheme, a character who, ironically enough given Onstad’s future career, touts her own virtues in Act II.

“There are different weights of voices. It has to do with the thickness of the vocal cords and certain body types are better for certain things,” she explains. “I’m petite, and smaller frames generally house smaller instruments and sing lighter roles.” (As a point of contrast, Onstad is married to Michael Hix whose very tall frame houses a very big baritone. He is currently interim chair of the UNM Department of Music.)

Onstad returned home to New Mexico in 2012, earned her first master’s, in voice performance, in 2014 and her second, in counseling, in 2017. She then worked at a local counseling agency and as a voice coach while continuing to perform locally. As she grew in her multiple professional roles, she began to see “a real need for specialized psychological help for performing artists,” she says. “Athletes have it in the form of sports psychologists. I think of myself as a type of athlete.

Onstad’s own performance issues had less to do with classic stage fright than with holding herself back for fear of not being good enough or ready enough, which itself often stems from perfectionism. “A lot of times it’s not necessarily the classic stage fright,” she says. “Oftentimes I see a colleague have a certain type of confidence in rehearsal. They shrink when it comes to the performance.”

She saw it all around her. When people realized she was in the mental health field, she started getting late-night calls and texts from panicked colleagues and friends: I am so anxious. I have a performance tomorrow. Can you give me tips?

This reaching out required its own well of courage. “It’s really taboo to talk about anxiety in the community. We don’t speak about it openly because the competition is so high and there’s stigma around any type of mental health issue. Even admitting to a fellow colleague that having a lot of anxiety creates more anxiety,” she says. “You’re already at maximum vulnerability.”

That makes Courageous Artistry particularly valuable as a private space where the people behind the public personas can go ahead and be afraid, then work through it.

Onstad says she chose coaching rather than therapy because coaching allowed her to have clients all over the world. If she had offered therapy, she would have been limited to New Mexico clients unless she acquired multiple licenses.

Certainly, Onstad’s therapy background informs her practice but coaching, including her style of coaching, is very present and future-oriented, whereas therapy is heavily based in a past perspective.

Coaching, she notes, is not “Why do I feel the way I feel?” but more “How can I progress towards my goals?”

One of Kelder’s favorite exercises, one that has led to “lasting and significant change,” involved visualizing her life as a working actor: What would her day look like? What tasks would she accomplish? What job would she have?

Onstad launched Courageous Artistry just as the shadow of COVID-19 darkened the world. “I thought this is either terrible or wonderful timing,” she laughs. Onstad made sure it was wonderful, offering free webinars to help artists cope with the stress of diminished work opportunities and canceled performances. She now sees clients in person and on Zoom.

Meanwhile Onstad was experiencing her own learning curve as an entrepreneur and, taking her own advice, hired a business coach to lead her through this new world.

In addition to the free webinars, she drums up business through presentations at colleges and organizations, including Tulane University, UNM and Youth Opera of El Paso. She also gets referrals from voice coaches (that’s how Kelder found her), physical therapists and speech language pathologists, including, recently, a team at Duke University.

Onstad’s extensive career as a performer prepared her well for this new role. “I’m used to being in the public eye and presenting myself,” she says. “I’m used to poor odds, knowing the chance you take auditioning. You have to be brave. You have to be courageous and resilient. You have to learn.”

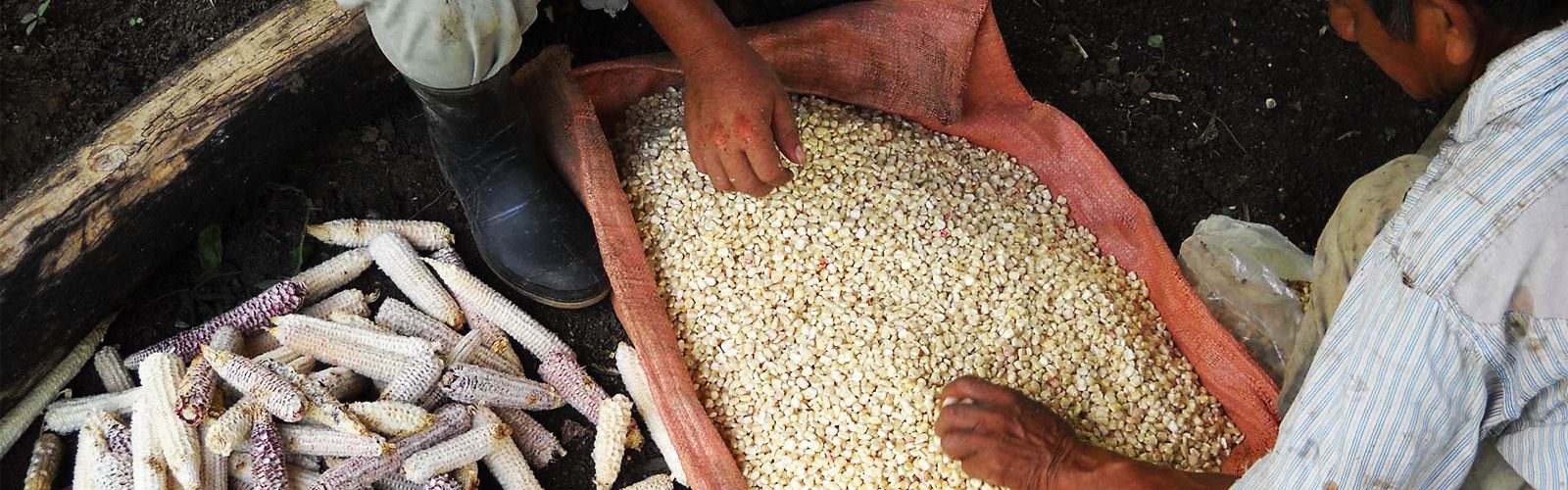

UNM archaeologist and Prof. Keith Prufer co-led a team excavating a site in Belize that uncovered evidence of how maize, a critical staple food in Central America, went hand in hand with human migration.

The paper’s title says it all. “South -to-north migration preceded the advent of intensive farming in the Maya region” was published in the journal Nature Communications in March.

Working in the remote Maya Mountains of Belize, Prufer’s team excavated 25 burial sites and, using stable isotope-labeled DNA, discovered evidence that farmers moved from the south 6,500 years ago, bringing with them seeds that changed the makeup of the region.

“We see the migration of these people as fundamentally important for development of farming and, eventually, large Maya-speaking communities,” said Prufer, who directs UNM’s Environmental Archaeology Lab. Maize — or corn — could be grown and stored, giving communities a reliable source of protein and sugar and allowing them to stay in one place.

UNM archaeologist and Prof. Keith Prufer co-led a team excavating a site in Belize...

The University of New Mexico Alumni Association

MSC 01-1160, 1 University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, NM, 87131-0001

Deadlines:

Spring deadline: January 1

Fall deadline: June 1

Robert “Bob” Cardenas (’55 BS) died in San Diego at the age of 102. Cardenas, a retired Air Force brigadier general, was an experimental test pilot and was awarded the Air Medal with two oak leaf clusters for experimental flight tests at Edwards AFB. His most notable achievement was piloting the B-29 launch aircraft that released the X-1 experimental rocket plane in which then Capt. Charles “Chuck” Yeager became the first human to fly faster than the speed of sound in 1947.

Jack Bresenham (’59 BSEE) Washington, D.C., was honored in the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Computer Society’s inaugural 2021 Class of Distinguished Contributors, which recognizes members for their technical contributions to the Computer Society and their profession at large.

Nasario Garcia

Ronald Kaehr (’70 BSME), Albuquerque, a father and grandfather, has completed his new book “Rogue Justice: Retribution.”

Bob White (’70 BA) Albuquerque, was named associate chief administrative officer for the City of Albuquerque. White has more than 40 years of experience as an attorney and public servant, formerly serving as assistant city attorney and city attorney.

Douglas J. Crandall (’71 BUS) was elected to a second term as president of the board of the New Mexico Retiree Health Care Authority, which administers insurance plans for more than 90,000 municipal, county, state and educational retirees and their families.

Raul R. Mena (’71 BS, ’75 MD), the medical director of the Roy and Patricia Disney Family Cancer Center, retired after four decades of caring for cancer patients at Providence Saint Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, Calif.

Grace B. Duran (’77 JD), Las Cruces, N.M., a judge in the Third Judicial District in Las Cruces, was appointed to the New Mexico Children’s Trust Fund Board of Trustees.

Anna L. Pool (’79 BA) has returned to Albuquerque after retiring from the University of Washington. She is currently editing another

memoir and researching her family history.

Shelly Armitage

Jack J. Dongarra

Bob Matteucci, Jr.

Shelley Armitage (’83 PhD), Las Cruces, N.M., was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters. Armitage is a professor emerita at the University of Texas at El Paso.

Jack J. Dongarra (’81 PhD) Knoxville, Tenn., received the 2021 ACM A.M. Turing Award from the Association for Computing Machinery for his pioneering contributions to numerical algorithms and libraries.

Bob Matteucci, Jr. (’82 BAS, ’08 JD) has been elected to serve on the New Mexico Bar Association Family Law Section Board of Directors.

Walter R. Archuleta (’81 MA, ’02 PhD), Santa Fe, N.M., was the recipient of the Matías L. Chacón Lifetime Achievement Award for contributions to bilingual education. The award was presented by the New Mexico Association for Bilingual Education at their annual conference.

James H. Hinton (’81 BA), Dallas, retired from his position as CEO of Baylor Scott & White Health, and has been named operating partner of the equity firm Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe.

Mike Hamman (’83 BSCE), was named New Mexico state engineer. Hamman was formerly the CEO and chief engineer for the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, the Bureau of Reclamation area manager and the City of Santa Fe’s water resources director.

Dianne R. Layden (’83 PhD), Albuquerque, was selected to portray the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the New Mexico Humanities Council’s Chautauqua program.

Martin Red Bear (’83 MA) is celebrating Native American culture and honoring military service members with a new piece of art that will be displayed in The Journey Museum & Learning Center in Rapid City, S.D. Red Bear was commissioned to adorn the outside of a tipi, choosing to paint 41 horses and warriors.

Edward Argueta (’85 BSCE) was honored by the Department of Defense with the Bronze de Fleury Medal for his exceptional service to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense and the nation during a career that spanned more than 35 years.

Gregor von Huene (’85 BSME) is chief engineer at Soleeva Energy Inc. in San José, Calif., where he is developing a hybrid solar photovoltaic panel that provides both hot water and electricity. The panel will increase the overall energy gain from the same roof space and will be manufactured in the U.S. for use in residential and commercial applications.

Russell “Rusty” Greaves (’87 MA, ’97 PhD) has been appointed director of the Office of Contract Archeology, a division of UNM’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology.

Sheila Hernandez (’87 BBA, ’89 MBA) has been named senior vice president at Summit Electric Supply in Albuquerque with the title “customer experience officer.”

Harvey Krauss (’87 MAPA) was named the director of economic development and senior planner for the town of Florence, Ariz.

Mike D. Petraglia (’87 PhD), Brisbane, Australia, has been named director of the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution at Griffith University.

JoLou Trujillo-Ottino (’87 BA) has joined Delta Dental of Arizona’s leadership team as its senior vice president of sales and business development.

UNM alumni Craig Webb (’87 BFA), Rudolfo Carrillo (’87 BFA), Judson Frondorf (’80 BFA, ’87 MA) and Angie Garberina (’88 BFA) were featured in “Saw. Conquered. Came.” at Six O Six gallery in Albuquerque.

Jim R. Keene (’88 BM), Atlanta, Ga., conducted The United States Army Field Band on the recording Soundtrack of the American Soldier, which won the Grammy Award for Best Immersive Audio Album.

Dave A. Sanchez (’88 BA), Washington, D.C., has been appointed director of the Office of Municipal Securities at the Securities and Exchange Commission. He was an attorney fellow at the SEC from 2010 to 2013 and was most recently senior counsel at Norton Rose Fulbright.

Cindy Lovato-Farmer

Deb Haaland

Tom Ducatte

Cindy Lovato-Farmer (’93 JD), a specialist in employment law with two decades of experience in legal and leadership positions at national laboratories, has been named general counsel at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Deb Haaland (’94 BA, ’06 JD), the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, spoke at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

Tom Ducatte (’98 EDSPC) is a sportswriter for North Country Living Magazine, a quarterly publication located in the Adirondacks region of upstate New York.

Bryan Biedscheid (’90 BA, ’96 JD) is chief judge of the First Judicial District, which encompasses Santa Fe, Los Alamos and Rio Arriba counties.

Carol C. Sánchez (’90 BFA), Orlando Leyba (’82 BFA), and Leigh Anne Langwell (’88 BFA, ’98 MFA) are included in a new exhibition at South Broadway Cultural Center showcasing the work of six artists reflecting on their experiences of the pandemic.

William V. McPherson (’90 BA), Henderson, Texas, who retired from the Houston Police Department in 2020, is Kilgore College’s police chief and director of public safety.

Julie Coonrod (’91 MS), dean of Graduate Studies at UNM and professor of Civil, Environmental, and Construction Engineering, has been named by The American Council on Education as a Fellow for the 2022-2023 academic year.

Garrett Young (’92 BUS) was promoted in December 2022 to partner and general manager at Microsoft corporate headquarters in Redmond, Wash.

LeManuel Lee Bitsoi (’93 AALA, ’95 BS), Cambridge, Mass., is vice president for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at Brandeis University.

Matthew T. Casados (’94 BSED), Santa Cruz,N.M., is the Rio Arriba County deputy manager.

Rhonda BeLue (’94 BS) joined The University of Texas at San Antonio as a Lutcher Brown Endowed Distinguished Professor in the Department of Public Health.

Savannah C. Partridge (’94 BSEE), Seattle, Wash., was chosen as the 2022 Honorary Fellow by the Society of Breast Imaging in recognition of her scientific contributions for advancing breast imaging techniques.

Elizabeth A. Garcia (’95 BA) has assumed the duties of chief clerk of the New Mexico Supreme Court.

Tieraona Low Dog (’96 MD), Austin, Texas, has been elected to the American Botanical Council’s Board of Trustees.

Maria E. Sanchez-Tucker (’96 BA), Santa Fe, N.M., has been named community services director for the City of Santa Fe’s Community Health and Safety Department.

Benjamin A. Baker (’97 BA) has been appointed interim director of the New Mexico Law Enforcement Academy, and serves as the deputy cabinet secretary for statewide law enforcement support at the Department of Public Safety.

Olivia Benally (’97 BSEE) Window Rock, Ariz., is the new chief executive officer of the Navajo Times Publishing Company Inc. and publisher of the Navajo Times newspaper.

She is the first Diné woman to serve as leader of the Navajo Times.

Rachel Hess (’97 MD), physician and scientist, was named associate vice president for research at University of Utah Health.

Maria De Varenne (’98 BA), Nashville, Tenn., has been named senior partner at FINN Partners, a leading global public relations agency. Varenne, a veteran news executive and former Tennessean editor, will be responsible for overseeing earned media strategy and content across print and digital channels for the company’s diverse clients throughout the Southeast.

Raven Chacon

Raven Chacon (’01 BA), Albuquerque, N.M., won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize in Music for his piece Voiceless Mass for the pipe organ. Chacon is the first Indigenous composer and first from New Mexico to win the prize.

Cynthia Chavez Lamar (’01 PhD), Alexandria, Va., has been named director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Lauren Keefe (’01 JD) is the new city attorney for the City of Albuquerque.

Donna Mowrer (’01 JD), is the new chief judge of the Ninth Judicial District, which includes Curry and Roosevelt Counties.

Camille Pedrick (’01 BA, ’05 JD), Albuquerque, is the new executive director of The New Mexico Board of Bar Examiners.

Benjamin Petre (’01 BA) Denver, Colo., joined the international law firm Dorsey & Whitney LLP as a partner in its Denver office.

Dylan Miner (’03 MA, ’07 PhD), a founding professor in the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities at Michigan State University, has been appointed dean of the College.

John W. Blair (’04 JD), Santa Fe, N.M., is the new manager of the City of Santa Fe.

Ganesh Balakrishnan (’06 PhD), Albuquerque, was appointed director of The New Mexico Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, which works toward building the state’s capacity to conduct scientific research.

Kathy Dong (’06 PHARMD, ’06 MBA) joined the early-stage biotechnology firm Neuron23’s board of directors.

Eric J. García (’06 BFA) Roswell, N.M., presented his exhibit “Space Invader” at the Roswell Museum. The Roswell artist-in-residence’s work shines a light on the dark past of the Americas, and the reality of an authentic “alien” invasion of frightening proportions when Indigenous people clashed with “aliens” from the European continent.

Luis Brown (’07 BBA, ’09 MBA) has been hired as the information technology director by the Village of Los Lunas.

Leah Chelist (’07 BUS) is the new Executive Vice President for People at Denver-based NexCore Group, a national health care real estate developer.

Marcos Gonzales (’07 MBA) was recently promoted to director of the Bernalillo County Economic Development Department.

Shammara Henderson (’07 JD), Albuquerque, a New Mexico Court of Appeals judge, was honored with the Albuquerque Section of the National Council of Negro Women’s Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune Legacy Award. The award acknowledges work with the National Council of Negro Women and the Black community in New Mexico.

Jason R. Patton (’07 BSNE), Gales Ferry, Conn., a U.S. Navy commander, is executive officer of the NAVSEA Warfare Center’s Naval Undersea Warfare Center Division Newport in Rhode Island.

Rebecca Chavez (’08 BA), an MD, completed the surgical critical care fellowship program at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, N.Y., a hospital affiliated with New York Medical College School of Medicine.

Shanna M. Combs (’08 MD), Fort Worth, Texas, a practicing physician with the Cook Children’s Physician Network, has been named president of the Tarrant County Medical Society.

Emma Nolan (’08 MWR) is the new principal managing broker for Coldwell Banker Bain’s Edmonds/Lynnwood office located in Seattle, Wash.

Myrriah Tomar (’08 BS) received the 2022 Women in Technology Award from the New Mexico Technology Council. Tomar is the executive director of New Mexico Tech’s Office of Innovation Commercialization and serves as a member of President Stephen G. Wells’ senior staff and cabinet.

Melanie Barnes (’09 PhD) was named state director for the Bureau of Land Management, and will oversee 800 employees, 13.5 million acres of public lands and 42 million acres of federal minerals.

Tim Hoyt

Ashleigh E. Olguin

Tim Hoyt (’10 PHD) serves as the deputy director for Force Resiliency in the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel & Readiness. He oversees military-wide policy and programs related to suicide prevention, sexual assault prevention and reducing illicit drug use.

Ashleigh E. Olguin (’15 BA), Albuquerque, was promoted director of contract administration at Friday Health Plans.

Ruben Olguin (’10 BA, ’15 MFA) focuses on acoustics and incorporates sound frequencies in his series “Anthropogenic frequency,” part of the Arrivals 2022 exhibition at form & concept gallery in Santa Fe. Olguin’s series consists of vessels 3D-printed in plant-based plastic filaments infused with wood, which hold specific frequencies isolated to the optimal sound to stimulate the growth of specific plants, such as basil, corn, tomato and mung bean.

Yagazie Emezi (’11 BA), Lagos, Nigeria, an artist and independent photojournalist, has had work published by Al-Jazeera, The New York Times, Vogue, Newsweek, The Guardian and The Washington Post. Emezi was awarded the 2018 inaugural Creative Bursary Award from Getty Images, 2018 U.S Consulate Grant from The United States Consulate General Lagos, Nigeria, and 2017 Distinguished Alumnus Award from The University of New Mexico African Studies Department. Three years ago, she made history by becoming the first black African woman to photograph for National Geographic Magazine.

Ernest I. Herrera (’12 JD), San Antonio, Texas, was named by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund as its Western Regional Counsel.

Eric J. Stephen (’12 MA), Tulsa, Okla., is an education and development specialist at Manhattan Construction Company, a national construction services firm.

Alex M. Greenberg (’14 BA, ’17 MBA), Albuquerque, is director of the New Mexico Economic Development Department’s Office of Science and Technology.

Jessica Leigh Streeter (’14 JD), Las Cruces, N.M., has been appointed to the Third Judicial District Court.

Fabianna Tabeling (’14 MACCT, ’19 MBA) has been named interim director of Popejoy Hall at UNM.

Matthew L. Bernabe (’15 BBA), Albuquerque, owner of Urban Hot Dog Company, was featured on the Cooking Channel’s show “Food Paradise.”

Eric G. Griego (’17 MA, ’21 PhD), Albuquerque, will serve as the City of Albuquerque’s director of outreach and advocacy, which seeks to engage the community in the policy-making process.

Alexandra Iturralde

Alexandra Iturralde (’20 BA) is a first-year graduate student at Duke University’s Nicklas School of the Environment.

Layla S. Archuletta (’20 MPA), Santa Fe, N.M., former staffer for U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich, is the City of Santa Fe’s deputy city manager.

News, notes and updates from UNM Alumni...

Dear Lobos,

Fall in New Mexico is a treat for the senses. With the arrival of autumn comes the smell of roasting chile, the sight of hot air balloons on the horizon and the vibrant, bustling sounds of student life on our UNM campuses. It’s easy to be excited about the season — and about the future.

For more than a year — and even during a globe-altering pandemic — The University of New Mexico has been working tirelessly with an engaged university community to craft a road map for the future of our university. That long-term plan, UNM 2040: Opportunity Defined, has given us a chance to think differently about how UNM can be more relevant, more visible, and more competitive as we make our way toward the middle of the 21st century.

We officially unveiled our plan at a celebration in the SUB this past May, with the help of some key Lobo leaders and the lively support of an engaged audience. As part of our plan, we’ve laid out five long-term goals to guide us along our path to excellence. I hope you’ll take some time to read the full strategic framework, but our five goals, briefly, are:

As our flag-bearers and ambassadors in communities around the world, our Lobo alumni are some of our most crucial allies in advancing our mission and helping us achieve these lofty goals. Your engagement and enthusiasm will always be essential to our success as a university — and with you at our side as we begin the work to turn our aspirations into reality, I have never been more optimistic about our future as Lobos.

Have a wonderful Fall, and let’s go, Lobos!

Garnett S. Stokes

President, The University of New Mexico

With the arrival of autumn comes the smell of roasting chile, the sight of hot air balloons on the horizon...

Recent Comments