Where There’s Smoke

Those respiratory consequences can be dangerous — even life-threatening. But Matthew Campen, PhD, a professor in UNM’s College of Pharmacy, sees another hazard hidden in the smoke.

Thanks to a five-year, $3.7 million grant from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, a multi- disciplinary team led by Campen will investigate how inhaled smoke particles travel from the lungs to erode the blood-brain barrier.

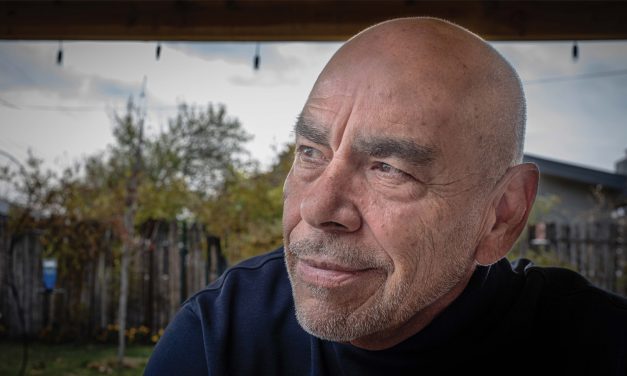

Matthew Campen

In research published online in the journal Toxicological Sciences, Campen and colleagues report that inhaled microscopic particles from woodsmoke work their way into the bloodstream and reach the brain, and may put people at risk for neurological problems ranging from premature aging and various forms of dementia to depression and even psychosis.

“These are fires that are coming through small towns and they’re burning up cars and houses,” Campen says. Microplastics and metallic particles of iron, aluminum and magnesium are lofted into the sky, sometimes traveling thousands of miles.

In the research study conducted in 2020 at Laguna Pueblo, 41 miles west of Albuquerque and roughly 600 miles from the source of California fires, Campen and his team found that mice exposed to smoke-laden air for nearly three weeks under closely monitored conditions showed age-related changes in their brain tissue.

The findings highlight the hidden dangers of woodsmoke that might not be dense enough to trigger respiratory symptoms, Campen says.

As smoke rises higher in the atmosphere heavier particles fall out, he says. “It’s only these really small ultra-fine particles that travel a thousand miles to where we are. They’re more dangerous because the small particles get deeper into your lung and your lung has a harder time removing them as a result.”

When the particles burrow into lung tissue, it triggers the release of inflammatory immune molecules into the bloodstream, which carries them into the brain, where they start to degrade the blood-brain barrier, Campen says. That causes the brain’s own immune protection to kick in. “It looks like there’s a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier that’s mild, but it still triggers a response from the protective cells in the brain — astrocytes and microglia — to sheathe it off and protect the rest of the brain from the factors in the blood,” he says.

“Normally the microglia are supposed to be doing other things, like helping with learning and memory,” Campen adds.

The researchers found neurons showed metabolic changes suggesting that wildfire smoke exposure may add to the burden of aging-related impairments.

Campus Connections

LatestJogging Memory

UNM's Jessica Richardson awarded grant to optimize treatment for the language disorder known as aphasia...

Spring 2022 Mirage Magazine Features

Big League

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

Read MoreFrom Prison to Poet

University of New Mexico alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca found peace in the written word…

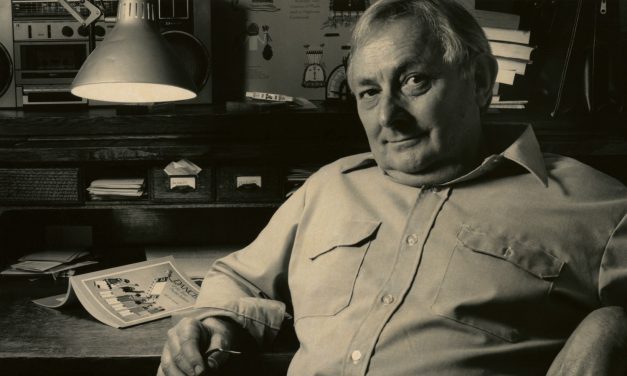

Read MoreProfessor Hillerman

In a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM…

Read MoreForm and Function

Among campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, UNM has always been distinctly of New Mexico…

Read MorePicture Perfect

You can thank an alumnus for creating the image technology that keeps us connected…

Read MoreMy Alumni Story: Joshua Whitman

When I decided to attend UNM I applied to live on campus because I wanted to become involved in student life…

Read More