Mirage: You graduated from Highland, and then I think you were 28 when you enrolled at UNM. What was happening in that decade between high school and college and what was it that propelled you to seek a college education?

Haaland: I was working at Zinn’s Bakery. I started that job when I was in high school. I walked to work every day after school. And when I graduated from high school, they offered me a full-time job. So, I took that and I just worked. It was important that I make a living by myself. My dad wasn’t the type to let anyone sit around the house, so not working was out of the question.

You know, I just woke up one morning and asked myself, “Am I going to be doing this for the rest of my life?” And the answer clearly was no. And at that point I called my sister, I called my mom and I asked them, “Should I go to college?” And of course, they said absolutely. Neither one of my parents graduated from college. I didn’t have a lot of people telling me I should go to college. So now I do that as a role model for kids. I just plant the seed sometimes. If I’m the only one asking them, you know, “Think about going to college,” then it’s absolutely important that I raise that.

Mirage: The path to college for a first-generation college student is a tough one. It took you awhile to graduate. I’m assuming you worked your way through?

Haaland: I was working. There were family obligations. I just wanted to do well and I thought if I don’t overload myself that I should be able to do well. And it was fine. Things happen the way they’re supposed to, I guess.

Mirage: And you were 34 and quite pregnant when you graduated. (Her only child Somah was born four days after graduation.) That sounds like a lot. And then you had a degree, you had a toddler and you started your own business, Pueblo Salsa.

Haaland: Yes, I kept that alive until I was in law school.

Mirage: Was that about the flexibility of being a single mom and being able to make your own hours?

Haaland: That was part of it definitely. I didn’t want to put my child in day care. I just felt very strongly that children in those young ages, it just lasts for such a short time, I felt very confident that if I kept her with me as much as possible, I would have a strong influence over her life. And as it is, they’re doing pretty well.

Mirage: Yeah, I looked at their social media. Cool kid! You’ve raised a really interesting adult who’s very impressive. I read a piece by Julian Brave Noise Cat in which he described in a really sensitive way this period of time when you really didn’t have enough food, were really down to nothing in the cabinet, and applied for food stamps. Can you talk about your financial struggles and how you coped?

Haaland: Right. Oh, my goodness. It’s tough. And so I understand that. It’s tough for so many people in this country. If I had all the money that I spent in overdraft fees, right? You just hold your breath every day because you’re worried about being able to keep things going, keep a roof over your head. I relied on friends and I relied on family. But I recognize that’s not a foolproof way to gain financial footing, either. That’s why I’ve been very adamant about helping to level the playing field. Equity is an issue in this country that we absolutely need to work on and deal with. People need to be able to support themselves. I remember filling out my application for food stamps and then telling me you don’t qualify for emergency food stamps and I just started crying in the counselor’s office. I know what it’s like to have to put food back when you’re at the checkout line because you don’t have enough money to pay for it.

Mirage: When you did decide to go to law school, were you thinking of a career as a practicing attorney or were you thinking of about getting into politics and just these kinds of social justice issues we’re talking about?

Haaland: You know, when I was in undergraduate, I had to take English 100 when I started because I didn’t score high enough on my standardized test, and my writing instructor would give us extra credit for going to lectures around the university and writing an essay about the lecture. And one of the first ones I went to outside of class was to listen to John Echohawk from the Native American Rights Fund. I was so impressed with him and his journey and work he was doing. He inspired me. And later on in my undergraduate career I took a class from Fred Harris, former senator from Oklahoma. He taught political science and he inspired me further. So I thought between those two I needed to go to law school.

Mirage: And after you graduated from law school, it was a law professor who put on the path of politics? Encouraged you to volunteer?

Haaland: My constitutional law professor invited me to apply to Emerge New Mexico and so I did that. I applied to Emerge New Mexico and the rest is history, I guess. I recognized that I could make an impact on things. Thereafter I just really dug in and started helping folks get out to vote. I was joined, of course, by many folks who feel passionate about our right to vote and so I was in really good company and have been for a long time.

Mirage: The rest is history! I look at your career as starting rather late in life, but then just taking off. From 2012 working for the Obama campaign to 2018 being in Congress yourself, that is a very short period of time. Did it seem like a real life-changing whirlwind?

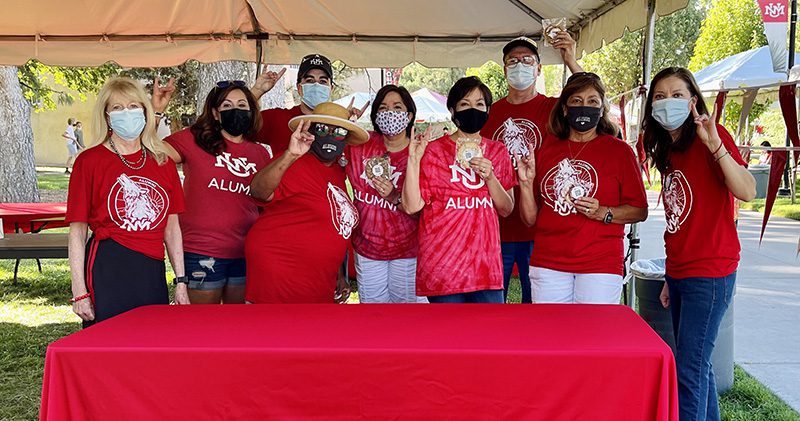

Haaland: It’s a good chunk of years, so it doesn’t necessarily feel like a whirlwind. But sometimes I stop to think how much has happened. I look through photographs I’ve taken that sort of document what I’ve done throughout the years and I think, yes, an awful lot has happened. It’s been wonderful. I’ve made some strong and beautiful friendships across the state. So it’s been great. And I’m still in touch with my college professors from UNM.

Mirage: When you were nominated for this job you spoke about the impacts of climate change and environmental injustice and the Interior Department addressing those issues. I wondered what you see as the core, the theme, of the work that you want to do.

Haaland: Climate change is real and if anyone thinks we’re not facing a climate crisis right now, I don’t understand that. It was a month ago or something the highest carbon levels ever recorded in the history of our world were recorded. So it’s an urgent issue. When you read the front page every day, they’re either talking about drought or wildfires. Our world is definitely changing. And I feel that every single American can participate in this new era that needs to happen and I really hope that every single person gets on board.

Mirage: You are famously the first Native American in charge of this agency and it’s an agency that has such a terrible history with Native Americans. So this isn’t just academic or policy for you – this is personal, right? Do you see that as an opportunity? Does it weigh on you?

Haaland: You know every position I’ve had weighs on me. If you’re a leader in anything you’re in that position because you care deeply about the issues, and I do. I care deeply. However, I feel very blessed that I’ve gotten so much support. For most things that I’ve done, even when I was a member of Congress, I had support across the country for the things that are important that we want to accomplish. So, I feel like I’m standing on the shoulders of so many people who came before me who worked hard to conserve our environment, who worked hard to bring issues to the forefront so that people will care about them and I feel like I am sort of honoring those people’s legacy and that’s a part of how I feel about the job that I have now. Many folks have come before me and I really need to stay on that trajectory.

Mirage: I’m curious how you stay grounded and connected – healthy physically and mentally in this period in your life.

Haaland: I’m a runner. I’ve been running for the last 20 years. And that absolutely keeps me grounded. Yesterday morning I got outside and ran eight miles. It was a beautiful New Mexico sunrise. I’m here in New Mexico and I’m going back to D.C. later today. I pack my suitcase with red chile and green chile and corn tortillas. I eat New Mexican food whenever I’m home. My mother taught us that those traditional foods. Yes, they keep your body healthy, but they also feed your soul, because we have a very strong tradition of agriculture here in New Mexico. When you partake of that it feeds your spirit as well.

Mirage: Are you training for any races right now?

Haaland: I am. I’m signed up for the Marine Corps Marathon Oct. 29.

Mirage: Is eight miles for a short run or a long run?

Haaland: When you train for a marathon, you increase your mileage incrementally. So I’m at eight miles. The next time I’ll run 10 and go up from there, my longest run being 20 miles before the marathon.

Mirage: Anything else you’d like to touch on about UNM?

Haaland: I would just say to the students at UNM, you’re so fortunate to be at an amazing university. It’s a close-knit community, everyone cares about each other. I loved my time there and I keep that tradition going.

My child, Somah, also graduated from UNM in the Theater Department in 2017. And so both of us, we recognize the value of being at hometown university like UNM. So just keep up the good work.

Mirage: So, a proud Lobo mom?

Haaland: Absolutely!

Recent Comments