New Faces

New FacesJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 The College of Arts & Sciences, UNM’s...

Read More

Story by Leslie Linthicum Photos by Roberto E. Rosales

Richelle Montoya, who had been a convenience store clerk, executive assistant and the elected president of the Torreon Chapter — one of 110 local government entities on the reservation — was sworn in as the nation’s first female vice president.

When Montoya (’11 BUS) spoke at her inauguration, she said in Navajo, “You are all my children.”

Montoya says that is the principle that guides her as she takes on the biggest and most demanding job of her life.

“I feel that somebody needs to be protective of my family, my children,” she says. “I feel that our men, they haven’t done that. If they did, we wouldn’t have domestic violence.

If they did, we wouldn’t have, unfortunately, incest. We wouldn’t have rape. And so I feel that myself and other women in leadership positions, we have that role now.” Montoya relates her serpentine path to a college degree and myth-busting election at the end of yet another long day as the vice president of the Navajo Nation. Decked out in her customary velveteen blouse, concho belt, turquoise necklace and Apple iWatch. She has been up since 5 a.m. participating in the Northern Navajo Nation Fair, waving to the crowds from the Navajo Nation float in the legendary Saturday morning parade, and then driving from Shiprock to Albuquerque to get a little sleep before a 4 a.m. wakeup call to represent the tribe at the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta.

Life has changed dramatically for Montoya since she first applied to join the Nygren campaign and then listened to the election results on election night. She moved from her home into the official residence of the vice president in the Navajo

Nation capital of Window Rock, Ariz.

She organizes her days around travel to communities around the vast reservation, which spreads into the states of Arizona, Utah and

New Mexico, and meetings in Window Rock with constituents, often fueled by a white chocolate mocha from Starbucks.

Recently separated from her husband of 11 years, a split she attributes in part to the pace of her new job, Montoya lives with her adult son Trenedad, who she can rely on to keep the house running.

“At this point, don’t even ask me how much a gallon of milk is,” Montoya says. ” I’m not going to the store.”

Montoya was born and raised in Torreon, the easternmost community on the reservation. By the time she was nearly 30 she had bounced between her home, nearby Cuba and Albuquerque working at a series of jobs at convenience stores. She was working as a clerk at the 7/11 in Cuba and taking care of her three young children when her older sister suggested she apply to the Albuquerque Public Schools temp pool.

She got hired and wound up answering the phones for the Indian Education Program. Her boss, Nancy Martine Alonzo from the Ramah Navajo community, eventually hired her fulltime, then promoted her to executive assistant and then data technician.

Alonzo, who was working toward a master’s degree in education administration at UNM, then gave Montoya the bad news. Without

a college degree, she could never move up further in the school district. She encouraged Montoya to go to college.

“She talked to anybody and everybody who worked for her about education and how important it was,” says Montoya.

Montoya took the advice seriously, but when her mother suffered a heart attack, she moved back to Torreon to help her recover.

It took her sister’s prodding and example — Vivian Montoya-Watuema enrolled at UNM and earned her BA in 2009 — to persuade Montoya she could have a place in higher education. Starting at CNM in Albuquerque, Montoya studied police science, then transferred to San Juan College in Farmington, where she received her associate’s degree.

When she walked by a UNM recruiting table at San Juan, she realized she could pursue a bachelor’s degree at UNM without leaving Farmington, where she had settled with her husband Olsen Chee and their blended family of six children.

Montoya enrolled and took all but one of her classes at a UNM satellite in Farmington.

By the time she walked with her graduating class at the Pit and received her diploma in University Studies, Montoya had no grand plans for a career, “I just wanted my degree, that was it,” she says. “I wanted that piece of paper, that diploma that said, Richelle Montoya finished something.”

With her husband no longer able to work, Montoya took a job as executive assistant at DNA-People’s Legal Services in Window Rock, and she spent a lot of her time chaperoning her daughter Autumn during her 2018-2019 reign as Miss Navajo.

Montoya also began to consider public service. Her father had served as chapter secretary and vice president in the Torreon chapter and had encouraged his children to be involved.

Montoya joined the local school board and then, frustrated that issues such as domestic violence and language preservation weren’t being adequately addressed, she ran for and won the election for chapter president.

“I became president of my chapter because no one was listening to me,” Montoya says.

She met the future Navajo President Nygren when he spoke to her chapter via Zoom during the pandemic and then called her up after the meeting to ask how he did. She eventually joined his campaign and was then asked to apply to be his running mate.

She liked Nygren’s story — like her, he was the child of divorce who lived without electricity and running water and spoke Diné fluently. And, like her, he was committed to bringing services in the sprawling nation up to date and solving problems by consensus. She was also impressed that he was committed to picking a woman to serve beside him.

“One of the things that I’ve always done in my family is we don’t have gender roles,” Montoya says. “I always brag that my daughters can go outside and chop wood and do oil changes and my sons can make food, do the laundry, clean the house.”

In her new job, Montoya believes she brings an approach to decision- making rooted in a long line of matriarchs who went before her.

“I feel that I bring the perspective of, ‘Slow down, let’s look at this issue from every single aspect that we can — yours, mine, hers, his, theirs. And let’s see what solutions everybody has. Let’s see which one has worked, which one hasn’t worked and let’s not repeat what’s not working.’

And a lot of the time, it’s just me listening.”

During the campaign, Montoya talked openly about her history with domestic violence. Her mother, who was married at 14, suffered abuse at the hands of her father, which led to their divorce. Her grandmother was also abused and her daughter had experience with a controlling boyfriend.

“I have three biological children,” Montoya says. “Each one of them has a different dad, and each one of the relationships ended because of domestic violence. And I kept saying, ‘No more. I’m not going to do this.’”

Although domestic violence was not part of the administration’s platform, women come to Montoya to seek help and she listens and tries to iron out red tape that’s getting in the way of their obtaining protective orders.

“I feel like my mom’s mom went through it. My mom went through it. I went through it. My daughter got through it a little bit. And now I’m like, hopefully my granddaughter never has to.”

At the Balloon Fiesta in Albuquerque, Montoya got a balloon ride and time to be alone with her thoughts. She visits the annual fiesta to connect with the spirit of her late son, Romeo, who was born in Albuquerque on Oct. 5 and was held by his mom as she watched balloons float by.

While her family is central to Montoya’s life, she has drawn a wall between them and her official duties.

“One of my biggest asks of my family is not to be around,” she says. “That’s my way of protecting them.

I don’t want them to be around my office or events. I want them to be home. I want them to live their lives. I want them to continue to do their traditions, their prayers, and everything they possibly can do to include me in on those because, of course, I need it.”

Understanding HeadwatersJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 A $2.5 million grant from...

Read MoreNo Je or No Sé?Jan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 In his research, Associate Professor...

Read More‘A New Pair of Eyeglasses’Jan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 Nancy López,...

Read MoreSenate Judiciary and Mental HealthJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 Colin Sleeper, a...

Read MorePlant PowerJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 More people are choosing plant-based...

Read More

By Ellen Marks

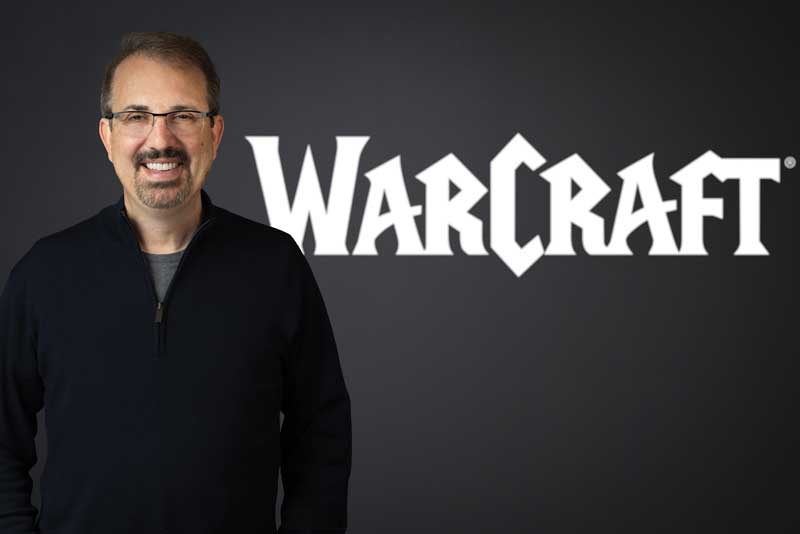

That kid was John Hight, who is now creating fantasy worlds for a global audience as senior vice president and general manager of the World of Warcraft gaming franchise.

The franchise, which has been a major critical and commercial success since its release in 2004, allows huge numbers of people to play against each other at the same time in online role-playing games. A 1985 University of New Mexico graduate, Hight oversees game development and operations of the franchise, which is owned by Blizzard Entertainment.

Previously, he worked for Sony Computer Entertainment America and Atari, Inc. All told, he has worked on 56 games and interactive products.

If you have a favorite feature or place in World of Warcraft, you can probably thank Hight for having had a hand in developing it.

“Over 260 million people on our planet have, at one time or another, played a Warcraft game,” says Hight, 63, of San Clemente, Calif. “Our mission statement is to build a fantasy universe that delights and connects everyone everywhere. We want you to come here, escape, be who you want to be.”

Hight, who won a Distinguished Alumni Award from UNM’s School of Engineering last year, showed a kind of genius for programming early on. He was an undergraduate at UNM when he agreed to help his older brother, George, modify an early version of a computerized general ledger system for George’s Albuquerque accounting practice. George Hight said his brother’s work involved moving a basic business operating system to personal computers, which was “really way ahead of its time for 1983.”

The brothers and several others spun off those innovations and started a company that subsequently sold for a healthy profit. In fact, the younger Hight was able to buy a house in Taylor Ranch, becoming a homeowner before he turned 21.

“It took a very powerful intellect to be able to work at the core level of computers to move the operating system,” says brother George, who lives in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. “He’s brilliant.”

At the same time, John Hight says he started “tinkering and writing little (computer) games on the side. And I kind of dug it.”

His initial career dream of marine biology (he still keeps a 200-gallon saltwater aquarium in his office) morphed into computer science, with an interest in fine arts. He says he wanted to start learning about “things that were more entertainment-oriented,” feeding his growing interest in computer graphics and gaming.

“It took a very powerful intellect to be able to work at the core level of computers to move the operating system.”

The New Mexico native, whose first job was at Clark’s Pet Emporium in Albuquerque, decided to combine his skills in programming and storytelling and produce what are now called massively multiplayer online games.

After getting his degree in computer science at UNM, Hight went on to earn a Master’s in Business from the University of Southern California.

Although he has gone far afield to market Blizzard’s games around the world, he and his family return three or four times a year to a 150-year- old casita they own in Santa Fe.

“It’s a home away from home,” he says. “I wear my boots and cowboy hat. I don’t do that here (in California) at all.”

The Hight family has a long history in Gallup, where the future gaming guru grew up.

Hight’s grandfather was a mayor of Gallup, and his father was a city councilor and mayor pro-tem. One

great-uncle served as police chief; the other headed the fire department.

The younger Hight started taking college classes at UNM’s Gallup campus when he was a junior in high school.

In elementary school, Hight spent a lot of time playing with classmates from the Navajo Nation, who were often bused in and sometimes lived in off- reservation dormitories during the week. Hight and his family lived directly across the street from Red Rock Elementary.

John Hight melds computer science with storytelling. (Photo: Blizzard Entertainment)

Those childhood experiences were in his mind when he created Hecubah, the main antagonist in the game Nox, who is queen of a tribe called the Necromancers. (The character is named after a caiman Hight’s brother kept until he had to donate it to a zoo.)

According to the plot line, Hecubah was left behind as a child, but she learns about her heritage and the great war waged years before between humans and her people, the Necromancers.

“WoW was a game that actually brought thousands of people together in a single server,” Hight says.

“She can resurrect the dead, but rather than have her just be this evil thing, I wanted us to understand what her culture is all about,” Hight says. He would like players to understand that she’s “really just protecting her people.”

“Through the course of the game, as you’re attacking her, as you’re fending off her and her minions, you’re beginning to realize that it’s cultural identity that’s important and… you are basically making assumptions about what’s best for the world. You’re trying to take her out and, what you’re really committing is, to some extent, genocide.”

In fact, Hight says, much of the entertainment industry is wrestling with “how to come to grips with this — here in America: Who are we and how are we excluding some and including others? What is our cultural identity?”

Blizzard’s latest addition to its product line is Warcraft Rumble, which is for a younger audience, Hight says.

While it’s like other role-playing games in that it can last for hours, it also can be polished off in a three- minute session — “perfect for waiting for the bus or for Uber,” Hight says. “This generation does not want to wait for anything. They want it now.”

The company releases games periodically to keep things fresh and to make sure the brand remains relevant, Hight says. World of Warcraft, known to gamers as WoW, is nearly two decades old, launching “before Facebook (when) people were just beginning to create their own webpage.”

In other words, eons ago, technologically speaking.

“WoW was a game that actually brought thousands of people together in a single server,” Hight says. “You could run around as an avatar. You might be a dwarf, I might be an elf… and we could interact with each other. More important, we were part of the online experience. So it wasn’t just a game, it was a manifestation of us being online.”

The game has attracted a second generation of fans who grew up playing with their parents. And one of its more famous is an 80-year-old woman, known as “WoW grandma.”

“She has a big following of people,” Hight says. “She streams her playing. She’s flown out here, and I’ve met her.”

Hight also has inspired fans among his many colleagues over the years. Holly Longdale, WoW executive producer and vice president, says Hight is exceedingly modest, so “the depth and breadth of his experience and expertise in this field is not widely recognized.”

He has developed “games that are pivotal in how we make games now. He’s like a delightful nerd. He’s everything we need.”

Alumni Association President Jaymie Roybal wants to connect with students before they become alums

Read MoreAlumna’s children’s books help Native kids see themselves in literature

Read MoreCarlos Servan (’93 BA, ’95 MPA, ’97 JD) has thrived since losing his sight at age 22 “Just...

Read MoreRichelle Montoya (’11 BUS) is the first woman vice president of the Navajo Nation

Read MoreMeet the UNM alum behind the fantasy universe of World of Warcraft

Read More

By Jenny Block

Goldberg grew up in Albuquerque, the youngest of three children raised by a single mother. When she was 17 and attending Manzano High School, she performed stand-up for the first time at her high school talent show… and she won, despite it not going quite as planned.

“I was wearing a pair of jeans, a button-down and a tie with polar bears on it, and I’m talking about my boyfriends and why it’s not working out so well,” Goldberg said. “And now I’m like, maybe it wasn’t working out so well because of my tie and button-down collection.”

Goldberg (’01 BA), who makes her living today as a working writer and comedian with a standup routine based on observational humor and politics, says comedy is something that has always lived inside of her.

“When I was younger, I used to listen to the Comic Relief team with Whoopi Goldberg, Robin Williams and Billy Crystal,” she says. “I don’t think I realized it at the time, but I was absorbing everything and I was studying and it was just something that I wanted to do.”

While Goldberg was attending The University of New Mexico, she went every year to see a show in Albuquerque called Funny Lesbians for a Change, which served as a fundraiser for higher education scholarships for women in the community.

“I saw some of my now colleagues headlining and I wanted to know what that laughter felt like,” says Goldberg, even though she would not get on a comedy stage for years.

Goldberg enrolled at UNM to study criminology and English, thinking she would teach English in prisons. She switched majors to communications with a math minor and finally landed on physical education, aiming to be a gym teacher, and graduated in seven years.

She came out as gay at 18 and found UNM to be a safe space as she found her community.

“I think just being able to go to such an outstanding school that was so close to home gave me an opportunity to continue to find myself being a newly out lesbian in a community where I felt accepted, I felt safe, and I felt like I could be myself on the campus,” Goldberg says. “It’s a place where people can feel safe and not just accepted, but celebrated.”

She bartended at Applebee’s to pay the bills while she was in college and student teaching. “Every once in a while, one of my students’ parents would come in and be like, ‘You made my child care about school again.’” Goldberg remembers.

“I affected the kids in the most beautiful way. I loved it. But I also had this dream gnawing at me that I really wanted to keep pursuing.”

Goldberg found she could make more money bartending full time than teaching and continued to attend Funny Lesbians for a Change when the show came through town. She confessed her dream of doing standup to the woman she was dating, who encouraged her to audition for the show. Goldberg finally took her advice but arrived after the audition closed and was told to come back in a year. During that year, the two stopped seeing each and the woman moved away. Not long after, Goldberg discovered that she had been killed in a plane crash.

“And, so, it was one of those watershed moments in your life where you go, ‘What do I really want to do?’” Goldberg says. “And she believed in me and she went to that audition with me. So, sort of in her memory and because of her encouragement, I went back and auditioned the next year and they gave me a seven-minute set in front of 650 people at the KiMo Theatre in downtown Albuquerque.”

The show was a turning point in Goldberg’s life. “I hit my first big joke and I heard the most deafening laughter I’d ever heard, and I was like, this is what I’m supposed to be doing. And I knew I wanted to be on stage.”

The 47-year-old, who now lives in Los Angeles, says things started falling into place after that. She performed regularly at a comedy club in Albuquerque and videotaped her sets. She sent the tapes to Olivia Travel, “the travel company for lesbians and LGBTQ+ women,” and got a gig. She is now a long-time regular aboard their cruises and on their resort trips.

“Dana is an incredible comedic activist and her ability to combine the two in an LGBTQ+ frame is so timely and effective,” says Judy Dlugacz, the co-founder and president of Olivia Travel. “Off-stage, Dana is caring and such a kind being! I have watched her grow up in comedy and am so proud of the work she does in such a smart, funny way.”

In 2007 Goldberg started a one- night comedy show in Albuquerque called The Southwest Funny Fest, which, up until the pandemic, she produced for 13 years.

The format brought together Goldberg and three other female headlining comedians from HBO, Showtime or Last Comic Standing for a one-night show to benefit either New Mexico AIDS Services or Equality New Mexico.

Albuquerqueans crave comedy and make for an incredible audience, says Goldberg, who made the show all-women to ensure women got the stage time they deserved.

“Most importantly, I wanted to continue to give back to a community that helped me get my start. And, so, it was a reciprocal relationship where I brought something to them that they wanted and they continued to come out and sell out the KiMo Theatre year after year.” She’s hoping to bring the show back this year.

In 2009, Goldberg’s career took a turn toward fundraising work when an auctioneer dropped out at a gala for the Human Rights Campaign in San Francisco.

“Someone on the board emailed me and said, ‘Do you know how to do a live auction?’ she recalls. “And I was like, ‘Let’s find out.’ So, I got on stage and I found a way to combine my comedy with some strange dormant gift of fundraising and live auctioneering that I never learned professionally, but just lives inside me, and pulled off one of the best live auctions that the gala had ever seen.”

Joe Solmonese, the president of the Human Rights Campaign at the time, was so impressed with Goldberg’s performance that he invited her to be a part of HRC and the organization’s national dinner in Washington, D.C.

“And so later that year,” she says, “I got on stage and went on between then-President Barack Obama and Lady Gaga.”

When Goldberg emceed, organizations raised big money.

“I found a very beautiful combination of comedy and fundraising,” she says. “When people are happy, they donate and they give.”

“Her remarkable talent for injecting humor into our advocacy efforts, all while mobilizing crucial resources for pressing causes, is unparalleled,” Says Kelley Robinson, the current president of the Human Rights Campaign & Human Rights Campaign Foundation. “She effortlessly blends laughter and heartfelt concern, providing both relief during tough times and renewed vigor to our mission.”

Working with HRC opened doors to the Trevor Project, GLAAD, Planned Parenthood, Lambda Legal, and other organizations. For the past five years, Goldberg has hosted the annual fundraising gala for the Child Rescue Coalition, a Florida-based nonprofit that helps law enforcement catch and prosecute child predators.

“She has been a big part of us growing that event from a small gathering of local supporters to being a sold-out and greatly anticipated gala in Palm Beach County,” says Carly Yoost, co-founder and CEO of Child Rescue Coalition. “People have described our event as being a wonderful ride that Dana takes you on, where one minute you are laughing, then brought to tears, then standing from your chair cheering.”

Goldberg’s career has allowed her to work with a roster of celebrities, including film and stage star Kristin Chenoweth. The two met at the Trevor Project gala and then finally shared the stage at the Gay Chorus of San Francisco gala in 2019, at which Chenoweth performed. After that, they continued to appear together at a number of events and became fast friends.

Chenoweth describes Goldberg’s topical humor as “balls to the walls.” “It’s something to behold when you’re watching her make everybody laugh,” Chenoweth says. “Not just people who agree with her — everybody. And not a lot of comedians, and dare I say women, have that quality, without overstepping. She can overstep and you still find yourself laughing.”

Chenoweth has long been an ally to the LGBTQ community.

“Comedians like Dana are so vital and so important to the community,” she says. “Not just to be heard, but to be able to laugh at oneself and to be able to discuss politics and laugh; and make it a meaningful conversation is really important. And she does all of these with aplomb.” As Goldberg reflects on her career, she is grateful for the life she has crafted and for the moments she will never forget.

“I get to do this because I know how to make people laugh,” she says. “I get to see the world because I bring joy to people, and there’s a value to that in our society. There’s a value to making people happy in our society.”

Robinson of the HRC agrees. “Her work has allowed us to gain the resources to elect more LGBTQ+ elected leaders than ever before and to mobilize more Equality voters than ever too — at a time when our world desperately needs real leadership,” Robinson says. “If you were to ask me for the name of one of the most important people that is fueling the movement for LGBTQ+ equality, I would say Dana Goldberg.”

Comic and alumna Dana Goldberg cracks people up while raising money for charity.

Read MoreGenerative artificial intelligence holds the promise — or threat — of changing higher education. UNM is preparing to use it to its best potential.

Read MoreFaculty Spotlight: Larry LeemanFeature, Spring 2024 By Leslie Linthicum Larry Leeman, MD, has...

Read MoreFrom thrash metal to a cruise ship symphony, composer Raven Chacon defies labels

Read More

Story by Ellen Marks Photos by Roberto E. Rosales

It’s an arcane question, and in the distant past it would have taken Perkins — a professor of medicine at UNM — a day or two to scour the literature and find an answer. In the near past, he could have turned to Google or another search engine to call up a list of possible answers, follow the links and try to determine which was accurate.

Instead, it took him 15 seconds using ChatGPT-4, an advanced artificial intelligence instrument that scours multiple sources to collate an answer, in this case 223.

It’s a tool that has people both fearing its doomsday potential and hailing it as a revolutionary step in education, research, ethics and likely every field of study at UNM.

“Some people are just despondent, thinking this is terrible,” says Leo Lo, dean of UNM’s College of University Libraries and Learning Sciences. “Some are optimistic, like me. Some feel it’s not ready for prime time, and that it has a lot of flaws. But the fact is it’s already here. Education will be changed forever because this thing happened.”

Like universities everywhere, UNM is struggling to understand what the world of generative AI will bring and how to best prepare for it and use it to its best advantage. And it’s doing so as the technology undergoes constant and rapid change.

“We’re trying to run as fast as we can,” says Perkins, co-director of the medical school’s MD/PhD program and board president of the state’s Bioscience Authority. “It’s changing as we talk. By the time we hang up, it will probably be different.”

UNM is among 19 universities in the United States and Canada that are participating in a two-year research project to prepare for advanced technology. The work is being done under the auspices of Ithaka S+R, a not-for- profit research group.

“…the fact is it’s already here. Education will be changed forever because this thing happened.”

Dean Leo Lo

Dean Leo Lo

Adrian Faust

Todd Quinn

There are currently no university-wide guidelines at UNM, other than the standard prohibitions against plagiarism and cheating, says Todd Quinn, an Ithaka team member and business and economics librarian in Libraries and Learning Sciences at UNM.

Generative AI is fundamentally different from basic artificial intelligence (think Siri or customer service chatbots) because it can create new content.

Melanie Moses, a UNM computer science and biology professor, describes it as “a new category of algorithms.”

“The basic technology hasn’t changed much in the last 50 years, but the impressive ability to generate new images and texts and videos, that’s really exploded in the last year,” says Moses, who runs a biological computation lab. “It is kind of astounding.”

The key to the explosion, says Moses, is new tools that rely on “billions and billions of lines of text to make predictions based on patterns in the past.”

Often, the results of a ChatGPT search can be so convincing that they are indistinguishable from what a human would create.

The technology has the potential for everything from addressing climate change or cybersecurity problems to finding cancerous tumors at a very early stage.

However, the tools, as they exist now, can yield grossly inaccurate results.

“Sometimes it just makes stuff up and then doubles down on its lies,” Moses says. “It can be quite misleading.” Lo pointed to an incident at Texas A&M University-Commerce this year in which an animal sciences instructor suspected at least some of his students had used ChatGPT to complete their work.

To test his theory, he fed some of his students’ writings into ChatGPT and asked it whether artificial intelligence had produced the work. The tool claimed credit for all of it and the instructor gave his entire class an “incomplete” grade.

Students unleashed an outcry, the university said it was investigating, and critics pointed out that ChatGPT is not considered a reliable resource for answering such a question. The university later said no students failed the class or were barred from graduating because of the issue.

“The tool is very good at synthesizing a lot of data but we’re seeing a lot of students getting fake citations” on research papers, says Lo, who is leading UNM’s six-member Ithaka team. “We have to tell them these don’t exist.”

Another difficult problem involves biases that plague the information found everywhere online. For example, a basic assumption is that doctors are men, so anything produced with generative AI is likely to have that bias, Moses says.

A case in point: An early AI model was asked to predict the winner of the 2016 presidential election. Contrary to what many polls had forecast, the model’s prediction was Republican Donald Trump over Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton.

“But then the question is why, and the why is, well, because men always win,” Perkins says. “Based on our culture, that’s correct, right? You could say it was pretty smart, but is it just reflecting, like a mirror?”

Moses points out that the gargantuan amounts of information that feed the intelligence tools can include outdated historical records, such as “books written in 1750.”

“Any stereotype you can come up with, these models tend to not just reflect them but exaggerate them,” Moses says. The internet is full of vile, violent kinds of text.

The internet, you might argue, represents the worst of humanity.” And what’s on the internet forms the building blocks for much of AI’s output.

Perkins says he offers a “positive spin” on the bias problem. Since our culture is full of biases anyway, he says, looking closely at what these new tools produce is another opportunity to examine humanity’s prejudices.

“It’s not like ChatGPT is making the biases up,” he says. “They’re in our culture, they’re in our data and in all these materials the (tools) have been trained on. It gives us another opportunity to confront them and address them and deal with them.”

And if there’s some resistance to adapting to the new AI reality, that’s probably to be expected, says Doug Ziedonis, MD, MPH, CEO of the UNM Health System and executive vice president of UNM Health Sciences.

Ziedonis, a psychiatrist, said he and other physicians chafed at the electronic health record when it was introduced years ago, and now accept it as part of medical practice.

“At a very high level, to me,” he says, “it’s not a question of if it’s going to happen. It’s happening. And I think that’s going to profoundly shift how we teach everybody.”

And how about what some say is the most frightening prospect of AI: that it could advance far enough to take over the world and make humans its slaves?

“It doesn’t keep me up at night,” says Moses. “My real concern with that way of thinking is that it puts the fear into something that’s in the distant future that no one feels like they can do anything about. It puts less attention on, we can make these algorithms better right now.”

But ask ChatGPT itself if it has any such apocalyptic plans, and the answer is an artificially intelligent “no way.”

“The idea of AI taking over the world is a common theme in science fiction,” the chatbot says. ”Generative AI, like the technology that powers me, is a tool created by humans to perform specific tasks. It doesn’t have consciousness, intentions or the ability to plan or make executive actions independently.”

Carter Frost, a UNM senior who is studying computer science, says he uses advanced AI extensively because “it’s quite useful for boilerplate stuff.”

It can write computer code and do other tasks that can easily be double-checked for accuracy, Frost says.

“Even when it’s wrong, it’s not mission critical, and I can just do it myself,” he says. “Ninety-five percent of the stuff it creates is correct or good enough.”

And while Frost says he doesn’t rely on ChatGPT to do his homework, he does use it to help with the intermediate steps of getting a project done, for example breaking a big job into smaller pieces – as long as there is no classroom ban on doing so. “It’s definitely saving me a lot of time,” he says. “It gives me time to work on maybe higher-level things… because a lot of the busy work has been taken away.”

Adrian Faust, also an undergraduate majoring in computer science, turns to AI for help in reviewing concepts he’s learned in the classroom. It can explain things that still might be fuzzy, he says.

And it’s that kind of potential as a “partner in learning” that makes Lo optimistic about a technological revolution. Say you’re out of your depth in a math class, he says.

The instructor has explained something to you several times, but it’s not getting through.

Before, “If I still didn’t get it, I didn’t get it and I’m stuck,” Lo says. “But (with AI), I could say, ‘Explain it to me like a 5-year-old.’ This tool is limited only by your own imagination, in some ways.”

Moses hopes that someday “everyone has an AI tutor who understands where they are and how to get to what they need to know.”

Students with a learning or other disability could receive specialized guidance to help them keep up.

“I can see it’s possible these tools could help students learn much better,” she says. “That’s much closer to possible than it was before these tools came out in the last year. Will we get there? I don’t know. It needs several pieces to fall in place.”

Ithaka S+R’s multi-university effort to get an academic handle on generative AI includes Ivy League schools, such as Princeton and Yale universities; large state universities like the University of Arizona and UNM; and smaller less well-known schools, such as Bryant University in Rhode Island and Queen’s College in Ontario, Canada.

The first step has been surveying faculty across each participating campus to “give us more insight into what’s happening locally,” Quinn says.

The UNM team is learning that some instructors are using generative AI to simply manage and respond to email. Lo, for one, does so, but he lets the recipient know when his response has a little artificial assistance.

Others are using it to “brainstorm concepts,” while some are “purposely using it in the classroom,” Quinn says.

What Quinn says he worries about is the effect on white- collar jobs across the economy, which are already being threatened by the capabilities of artificial intelligence.

“There are already places where AI does a good enough job for what we want,” he says. “That will mean disruption for many positions.”

One thing is certain, and that is universities will have to teach students to ethically and effectively use these tools as a job skill, no matter what field they end up in, several faculty members said.

“If you’re in the workforce, you need to know how to use this, or you’re not going to be very competitive as an individual, and also, your organization is not going to be,” says Laura Hall, a division head in the Health Sciences Library & Informatics Center and a member of UNM’s Ithaka team.

Says Lo: “People who know how to use AI will have a huge advantage. There’s a saying out there: ‘Humans are not going to be replaced by AI, at least in the short-term, but will be replaced by people who use AI.’”

Carter Frost

David Perkins

“Instructors may have to figure out other ways to assess learning.”

And if students are getting artificial assistance in doing homework, maybe they don’t need to learn whatever skills the homework is trying to teach, he says. “I think maybe this is a chance for us to rethink what education is. Maybe we use mental energy for something of a higher order.”

UNM as a whole, and certain academic departments, have started preparing for what’s ahead on the AI front.

For example, a new AI website — airesources.unm.edu/ — lists resources for students, faculty and staff. Ziedonis says he has budgeted $2.4 million to help Health Sciences begin preparing. And Moses is in an algorithmic justice group involving UNM and the Santa Fe Institute that seeks to “demystify algorithms and help everyone understand how they work in the real world,” according to the project’s website.

Moses also is writing to newspapers and speaking to legislators and other computer scientists about the coming implications of AI. She and several other professors spoke to UNM alumni on the topic at a Lobo Living Room session in September.

Such preparations are an initial step before the larger job of providing faculty support and training on how to use and teach the technology.

And that, Quinn says, will require money, although no one knows how much.

“Dollars for faculty to go to workshops, bringing people in to teach the tool in various disciplines, helping people overcome technological issues. I see a lot of training.”

Larger, wealthier schools are making big investments. The University of Southern California is spending more than $1 billion on a seven-story building that will house a new AI school and 90 additional faculty members. Oregon State University is planning a state-of-the art AI research center that will house a supercomputer and a cyber physical playground with next-generation robotics.

As for UNM, its contribution to the changing world might be its richly diverse student and faculty population, Quinn says. A recent New York Times ranking recognized UNM as No. 1 among the nation’s flagship universities when it comes to economic diversity.

“Having that uniqueness may allow for more voices we don’t hear from at a more elite university,” he says. “It may be if I talk about water, there are people who grew up… working around acequias or rivers or with farming. Those experiences can help come up with an idea using AI that we haven’t thought of before.”

Diversity is the touchstone for Davar Ardalan, a UNM graduate and founder of TulipAI, headquartered in southwest Florida. The company is using AI to find and produce audio sound effects, among other services.

Ardalan, a journalist and former National Geographic audio executive producer, says her work marries storytelling with artificial intelligence’s ability to cast a limitless net for content. Her company has a “strong commitment” to ethical practices that include making sure those who created the content are paid and bringing forward voices that are not often heard.

Although the future of AI is a daunting and sometimes scary prospect, it can provide sheer beauty that didn’t exist before, she says.

Ardalan and her sisters are creating an AI-generated collection of her mother’s writings, YouTube videos and other personal materials she produced before she died in 2020.

Ardalan’s mother, Laleh Bakhtiar — also a UNM graduate — was a renowned Iranian-American scholar who wrote, translated and edited more than 150 books.

The collection “will hold the body of her wisdom and allow a new audience to discover her. We can learn from her, even though she’s not here.”

As Ardalan seeks to unearth Native American and other lesser-heard voices, she is speaking out about the importance of teaching students how to use AI ethically and was part of a New York Academy of Sciences working group to prepare for what’s coming.

“This is one of the most profound technological moments of our generation,” she says. “We can form the creation of it.”

By Leslie Linthicum

He has also developed an interest in how psychedelic compounds can be used as medicines.

Putting those two interests together, Leeman is embarking this Spring on a study of how talk therapy combined with the use of MDMA (the compound in the party drug known as Ecstasy or Molly) might help new mothers recover from PTSD and opioid use disorder.

Mirage sat down with Leeman to talk about his research and the broader spectrum of clinical trials involving psychedelics that are being undertaken at UNM and across the country.

Mirage: I’d like to talk about the ‘psychedelic renaissance.’ There was a real explosion of research into the therapeutic potential of LSD and other psychedelics in the 1950s and 60s and then the research really was shut down for over 20 years. Rick Strassman in Psychiatry rebooted psychedelic research with his work with the psychedelic DMT at UNM in the 1990s. Now there’s Michael Pollan’s bestseller, “How to Change Your Mind.” And people are microdosing and there seems to be a new push for medical research using psychedelic compounds.

Leeman: When people describe a psychedelic renaissance, they tend to be talking about that from a Western and Anglo perspective. And I think it’s important, especially in New Mexico, to acknowledge that the use of psychedelic therapies dates back millennia in the Indigenous populations throughout the hemisphere. This wasn’t invented in the 70s.

Mirage: Noted. Research is about asking questions. What questions about the use of psychedelics interest you?

Leeman: I’m first and foremost a physician clinician. I’m very active in maternal and child health, delivering babies, taking care of people with addiction. And so a burning question for me is can these compounds help with addiction? Can they help with trauma? Can they help with PTSD? Preliminary research suggests yes, at least for MDMA for PTSD. But then, it gets deeper. It gets into what is it that’s effective about these? Do these psychedelic-assisted therapies work? If they do work, what are the psychological mechanisms? What is the best type of accompanying therapy? What are the biological mechanisms? Are there ways to develop new compounds?

Mirage: In these studies, using MDMA, psylocibin and ketamine along with psychotherapy, is it less about the emotional or psychological experience of having the drug on board and more about what that does in terms of the therapy that occurs?

Leeman: So the simple answer would be, we don’t know. We don’t know how important what you went through during the experience is. Most of us think it’s important, and that it forms the background for what we call the ‘integration,’ where insights that have been learned and processed can be integrated into one’s behaviors and one’s daily life. But that needs to be studied more.

Mirage: People who use psilocybin and MDMA recreationally report an increased sense of connection — connection to other people, to themselves, nature, the universe. How important is that aspect in your therapy?

Leeman: You’re talking to someone who’s an addiction medicine doctor.

There’s a quote that’s been used in the past that addiction is the opposite of connection. People that are addicted have a very narrow aperture. Eventually, it basically comes down to you and your substance, and that may be the only thing that you’re focused on. Almost everything else may be being manipulated to get your substance, and you will lose connection. I view connectedness as having multiple levels. One is the inner sense of connectedness, that we’re in touch with our own emotional feeling, self- awareness, our somatic state. The next level would be connectedness with your family, your partner, your community, your friends. And then the other level gets broader — our connection with the world or the universe. Those are three levels, some of the scales, that we’re using to look at that. A lot of this is theoretical.

We need to see what actually is associated with improvement in mental health and behavioral change. Because if we can figure that out, there’s ways to achieve some of these states without drugs. There are ways to achieve some of these states through meditation, there’s even forms of breathwork that you can use to facilitate these states of consciousness.

Mirage: So let’s talk about the study that you’re undertaking. MDMA-assisted therapy for helping relieve PTSD in postpartum women who are opioid dependent. What were your experiences at Milagro that led you to this research?

Leeman: When I first started working in addiction and pregnancy, I was taking care of the babies that had neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome. And then that expanded to interest in the prenatal care and the childbirth. Part of what I saw is that a large proportion of the people we worked with who we were able to get stabilized, usually with the help of medicines including buprenorphine or methadone, and through the pregnancy and initial postpartum time. But then I started seeing people coming back. Two years later they were pregnant again and back on opioids despite having achieved stopping use during and immediately after the last pregnancy, which is what they wanted. Sometimes we can all be slow to understand, but eventually I got it. Okay. We’re helping with the addiction. We’re helping with the craving for the opioids. But we’re not getting to what causes the addiction. I wasn’t doing anything to help them with their trauma, which is causing this self-medication with opioids. We weren’t actually treating the trauma. And PTSD has been notoriously difficult to treat, especially in the people who had it for a long time. So I started doing some exploration of what are the ways of treating that? One of the innovative ways was with MDMA-assisted therapy, which has demonstrated high levels of success, where about 70% of people after the course of treatment no longer meet the criteria for PTSD, about twice the proportion of people that are using a placebo in studies. The University of New Mexico supported me in doing a sabbatical in psychedelic- assisted therapies and addiction at Madison, Wisc. I was able to become a researcher and a therapist on their Phase 3 MDMA study to learn how to use MDMA-assisted therapy. One of the goals of that sabbatical was to come back here and bring this research and therapies to New Mexico.

Mirage: Why are you choosing to study a population that has PTSD and substance use disorder and recently had a baby?

Leeman: Yeah, so what’s the reason for studying these complicated people? Well, I guess there’s two ways of answering. First, that’s the people I’m taking care of. But on a deeper level, this is our future. In the families I work with I had trouble identifying anyone in the family that didn’t have addiction. It goes back multiple generations.

Mirage: Is the goal of this to have women who are having babies have safer and healthier experiences because they’re no longer using opioids? Or is it to have them have better experiences with their children because they’re having less trauma, less PTSD, and therefore more connection?

Leeman: All of the above. But we think that may happen in sequence. So what are our actual research objectives? One of them is seeing, can you treat PTSD in people that have opioid use disorder successfully with MDMA? The next part, which is major, is decreasing resumption of opioid use. We know that within the first 12 months after childbirth, over 50% of people resume use. In our study we will be watching people out to six months after treatment to see if they’ll be less likely to resume use of opioids. Resuming use of opioids has all sorts of bad outcomes. As you mentioned, it can affect your parenting. It can actually affect custody of your children if it gets bad enough. We see many pregnant postpartum people lose custody of their children. That’s a major life trauma. Another concern, unfortunately, is that a common time for overdose is postpartum. The last goal of the study is the most exploratory, which is looking at how the MDMA – assisted therapy affects parenting. We have a series of assessment tools that we’re using — the maternal-infant bonding assessment and a video assessment where we observe the study participant and we watch how they’re interacting with their baby. It’s based on the idea that trauma affects bonding and attachment.

Mirage: What’s the tie between trauma and addiction?

Leeman: When you look at causes of addiction, the roots are often in adverse childhood experiences. When we think of adverse childhood experiences, they can be various forms of trauma – Big-T or Little-T trauma. Big-T trauma is something major that happened- your parent is shot, you’re in a war, you experienced sexual abuse — those are all Big-T trauma. But the addiction is also associated with other kinds of trauma. You have a parent who’s emotionally absent and don’t experience feeling of love and safe attachment. Those are deep rooted. Our hope is that early in the lifespan of the mother and baby that we may be able to affect that. This is very preliminary, but we’re going to look at that both from the questionnaires and from the videos and from qualitative analysis by interviewing the mothers six months after completing the MDMA-assisted therapy. And if we do show that there’s a benefit, then we have a new treatment to help with intergenerational trauma. As we see commonly in New Mexico we are kind of in a cycle here. I call it a cycle of despair. People experience trauma, they have addiction, the addiction gets them exposed to more trauma, and the cycle continues.

Mirage: This is about the mother connecting with her trauma in a safe way and also encouraging connections between the mother and her baby. And MDMA is a possible avenue to both?

Leeman: You and I were talking earlier about connectedness, bonding that would be associated with being a new mother. MDMA is a complex chemical, and it works in different ways, but it does increase oxytocin release, which is the same chemical that is involved in maternal- infant bonding. The way MDMA- assisted therapy works, to the best of our knowledge, is that when the therapy is done in a safe container it allows people to process their trauma without the feeling of reexperiencing the trauma.

Mirage: While you’re doing this, are you actively doing therapy? Like asking them questions? Or are you letting this subject just experience the feeling?

Leeman: Great question. During the preparation system sessions, we’re getting to know them, we’re talking about their life. It’s relatively loosely structured and patient-led during the session itself. When you take people who’ve had significant trauma and you give them a compound that temporarily allows them to look at their life and that trauma without getting triggered by those feelings, I do not have to go, ‘Tell me about your trauma.’ People do it themselves. What happens during the session, which usually lasts about five hours, is they have a time when they’re lying down, they have eyeshades on and they have headphones with music. And then they speak with the therapists and share their experience. Commonly they go in and out — times of wearing eyeshades and times of talking. There’s an inner processing, where they’re usually thinking about these sorts of things. and when people come out of it, they talk and share about their experience. And what they’re doing through this is reprocessing the trauma, they’re kind of reframing it. It’s hard to heal from something, if every time you think about something, you go into fight or flight or freeze responses, then you really can’t process that. And we are giving people a temporary holiday from those trauma pathways. But we’re giving them that holiday in a way that they come out and talk about the trauma and have the potential to heal through that.

Mirage: Is there still a stigma to this type of research, especially in the National Institutes of Health, which is a major funder?

Leeman: I think the stigma didn’t originate in the NIH. I think the stigma originated in society.

There’s still a lot of collective cultural memory from the time of the 1970s, when these became part of the culture wars. And in the late 60s and 70s there was an overenthusiasm of some thinking that using these substances was going to change the world. I think we’re societally reframing that to ask, what is a substance of abuse and what is potentially a therapeutic medicine? There are very promising studies that are out there — psilocybin for major depression, MDMA for PTSD, psilocybin for alcohol or tobacco use. As those have come out, the NIH has become interested in and welcoming of research into psychedelic-assisted therapies. They’ve looked at the studies, they’ve had conferences, and they’re starting to support that. It’s still small, but hopefully, there’ll be a lot more. I’m optimistic that, at UNM, we’re in a position to be at the forefront of that area, particularly with addiction and trauma, because we are a major epicenter of opioid use disorder. And most of the early studies of psychedelic medicine occurred with white males. So, we want to also make sure this is being studied in a multicultural population.

Recent Comments