New Faces

New FacesJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 The College of Arts & Sciences, UNM’s...

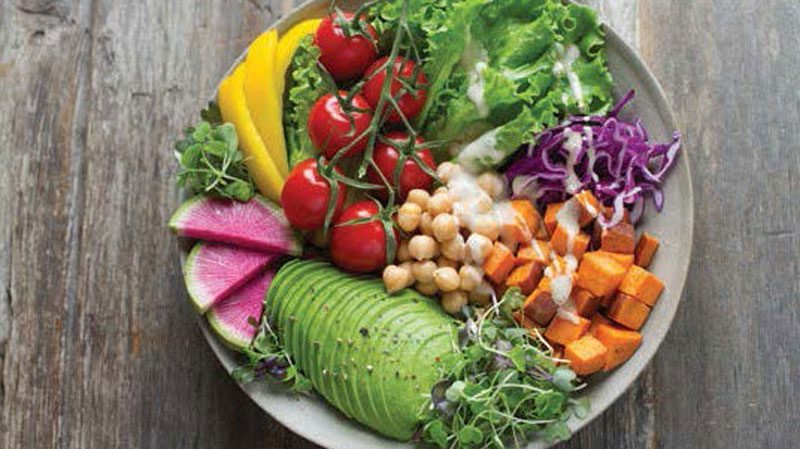

Lama Lteif, a former nutritionist who is now an assistant professor of marketing at the UNM Anderson School of Management, has devised a framework of four values that drive the trend toward plant-based eating.

Her 2023 article in the Journal of Consumer Psychology, “Plant Power: SEEDing our Future with Plant-based Eating,” shares a new way to look at why people are choosing plant-based diets and the benefits of this shift. Building on data from the 2021 Rockefeller Foundation report to explain people’s food choices, her work features a framework showing the values that drive consumers toward plant-based eating. The framework is called SEED: Sustainability, Ethics, Equity and Dining for Health.

“By understanding how these values influence decision- making, individuals and marketers alike can make better choices for themselves, inform their marketing strategies and give more attention to the issues that mean the most to them,” Lteif explained.

Those who relate to the sustainability value have growing concerns about animal farming and its role in climate change. For those whose ethics affect their eating choices, concern for animal safety and well-being drive meal choices away from meat and dairy. Food equity concerns refer to offering all people affordable access to food and the ability to cook and store the food that allows them to thrive. The dining for health value supports the connection between a plant-based diet rich in fruits and vegetables, fiber, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants, with health benefits.

Lteif likens these value-based choices to a seed’s root system, where the “SEED values connect and as a group can influence a person’s eating habits. If embraced by society as a whole, these values can transform systems to be more friendly to our environment, more fair and more nourishing.”

New FacesJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 The College of Arts & Sciences, UNM’s...

Alumni Association President Jaymie Roybal wants to connect with students before they become alums

Read MoreAlumna’s children’s books help Native kids see themselves in literature

Read MoreCarlos Servan (’93 BA, ’95 MPA, ’97 JD) has thrived since losing his sight at age 22 “Just...

Read MoreRichelle Montoya (’11 BUS) is the first woman vice president of the Navajo Nation

Read MoreMeet the UNM alum behind the fantasy universe of World of Warcraft

Read MoreComic and alumna Dana Goldberg cracks people up while raising money for charity.

Read More

Quantum science is at the heart of our smartphones and GPS devices. UNM has graduated more than 40 doctorates in physics who are now leaders in academia, national labs and industry across the nation. The Quantum New Mexico Institute aims to develop talent in the multidisciplinary field that uses quantum mechanics to solve complex problems and develop information technologies.

“Our vision is to make New Mexico a destination for quantum companies and scientists across the world,” said Setso Metodi, the institute’s co-director and Sandia Labs’ manager of quantum computer science.

The institute’s interdisciplinary foundation will include several departments across the University, including Chemistry & Chemical Biology, Computer Science, Electrical & Computer Engineering, Mathematics & Statistics, and Physics & Astronomy. UNM students will have expanded opportunities to participate in collaborative research between UNM and the national labs.

Within the last 10 years, the partnership between UNM and Sandia Labs has cultivated an atmosphere of teamwork with the participation of faculty, postdoc and student researchers involved in the UNM Grand Challenges program and a variety of collaborative research projects.

New FacesJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 The College of Arts & Sciences, UNM’s...

Generative artificial intelligence holds the promise — or threat — of changing higher education. UNM is preparing to use it to its best potential.

Read MoreFaculty Spotlight: Larry LeemanFeature, Spring 2024 By Leslie Linthicum Larry Leeman, MD, has...

Read MoreFrom thrash metal to a cruise ship symphony, composer Raven Chacon defies labels

Read More

By Leslie Linthicum

They all have one thing in common: A date in the courtroom with Jaymie Roybal.

Roybal, 33, who assumed the title of president of the UNM Alumni Association last year, has been a federal prosecutor since 2019 and carries a caseload that is about half violent crime and half child sexual exploitation cases. She takes on bad actors and she wins, too.

So it’s a little surprising when Roybal (’12 BS/BA, ’16 JD) tells the story of bursting into tears in her first-year criminal law class at UNM during a discussion of a case against a father who had kicked his 4-year-old son to death.

She’s nursing a chai tea and remembering some of the twists and turns that took her from an idyllic childhood in Española to representing the Justice Department in federal courtrooms. Roybal makes clear she is talking to Mirage as a proud Lobo, and not in her official capacity as an Assistant United States Attorney in the District of New Mexico.

Alumni Association President Jaymie Roybal outside the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals courthouse in Denver.

(Photo: Courtesy Jaymie Roybal)

“He was really sweet, and he told me, ‘You need to be able to read the material for the reason I’m trying to teach it — for the law.’ And I just couldn’t. I couldn’t get to the teaching part because it was really sad to me that this kid had died. That’s all I took away.”

Roybal got a C in that class. “Well deserved,” she says. And she decided that she still wanted to be a lawyer, but she could never do criminal law.

“I always tell that story, because you just never know where the universe is going to end up taking you,” Roybal says. “So now this is what I do full time. And I love it. And if there was a job that was, like, designed for me, it would be this.”

Roybal’s heart hasn’t hardened to the dark corners of humanity that she encounters in her cases.

“I still cry. I just do it in my office now, not in the courtroom,” Roybal says. “But I think you can’t lose that human element, right? Because it’s easy to be jaded. It’s easy to just kind of move the case from point A to point B. But working with victims is just the best. Because you can’t ever undo something bad that’s happened to someone, but you can help them close this bad chapter and go forward.”

Roybal grew up in Española with family at the center of everything. Her dad taught accounting at Northern New Mexico College and her mother worked in the Santa Fe office of Richard Rosenstock, a civil rights lawyer. Life revolved around church, volleyball, grandparents, aunts and uncles and cousins, and work at the family farm in Chamita.

“It was really a picturesque childhood and I’m so grateful that I grew up there,” Roybal says. She attended Pojoaque High School, where she played volleyball, served as class president, worked on the yearbook and was in the National Honor Society.

Roybal came to UNM because it was a family tradition and found herself as a 17-year-old freshman sitting in a psychology class in Woodward Hall with 800 other students — about six times the number of people in her senior class in high school.

Like other freshmen from smaller towns, Roybal managed to find her way at UNM and surprisingly discovered a supportive community in the Signed Language Interpreting major in the Department of Linguistics.

Although one of Roybal’s grandmothers had lost her hearing and the grandkids communicated with her by passing notes, Roybal had no particular passion for signing. She was just having trouble fulfilling her foreign language requirement and someone told her the ASL classes were easy.

“So I took it and it was not easy!” Roybal says. “It was so hard. But I loved it. And the program at UNM is such a gem.”

When she graduated in 2012 it was with a Bachelor of Science in Sign Language Interpretation and Translation and a bachelor of arts in Political Science.

Jaymie Roybal (Photo: Raymond Armijo)

“I took ‘you argue a lot’ as a compliment,” Roybal says, laughing.

When she got out of law school in 2016 fate found Roybal a clerkship with U.S. Magistrate Greg Fouratt, a former U.S. attorney, who encouraged her to consider criminal law and made observing prosecutors in the courtroom part of her job. One in particular, a young Hispanic woman named Marisa Ong, showed Roybal what might be possible.

“By the end of that clerkship,” she says, “I was hooked. I wanted to be in the U.S. Attorney’s office.”

Roybal was living in Washington, D.C., working on the policy staff of U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich and loving it when a job opened at the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Albuquerque. She’s been there since 2019. In addition to carrying a general caseload in the criminal division, Roybal runs the department’s Project Safe Childhood initiative, which prosecutes the sexual exploitation of children.

It’s a demanding job, with high stakes and lots of hours. Roybal finds balance in learning to play tennis and golf and in her work with the Alumni Association board of directors, which she joined in 2017.

When she was asked to join, Roybal was already familiar with the association from her term as president of the Associated Students of the University of New Mexico in 2011-2012. And she remembered Office of Alumni Relations Director Karen Abraham’s advice that, wherever you are in your life or career, you can always find something to give back to UNM.

“Karen took me under her wing and she used to really emphasize to me that your service to the University goes beyond your 15 minutes of fame, so to speak. That you always have more to give to this place.”

“It’s a great board. It’s people that just love the University and love the campus, and they all love it for different reasons,” she says. “Everyone’s story is completely different. But this one place gave all of us an opportunity and a path that we walk on now.”

One of Roybal’s goals for her term as president is to connect with students, so they’re familiar with the Alumni Association before they graduate and become alumni.

“I will always believe that first and foremost, the University is to educate students. And the student base is our future alumni base,” she says. “So I want students to know that we see them, and that we care about them, and that we want them to graduate. And that we want them to become part of our alumni community.”

Expect to see Roybal’s “Lobo For Life” rollout on campus sometime this spring as Alumni Association board members fan out on campus handing out Lobo for Life swag and making connections that hopefully will pay off for students and board members down the line.

“I think that so much of what the Alumni Association does is foster that intangible kind of love for place. We’re about maintaining that connection, which then I think pays off in really tangible ways,” Roybal says. “I think one of the most important things that it does is help people find other people who can help you along the way.”

Story by Leslie Linthicum Photos by Roberto E. Rosales

They wanted their sons, like other children, to see themselves represented in the books that would help shape their young minds.

So Laurel, who graduated from UNM in 1985 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology and earned a master’s in counseling and family studies in 1989, made books of her own. She carefully glued photos of her sons and some of herself and her husband over the pictures in the books.

The books, charming and one of a kind, allowed Kalen and Forrest to see themselves, in their moccasins and ribbon shirts, as heroes of children’s literature. But the exercise was born of a necessity Laurel found disturbing. The boys are grown today, with careers in the arts and journalism, and the state of representation of Native Americans remains dismal.

Just under 2 percent of children’s books are centered around a Native American character and a little more than 1 percent of children’s book authors are Native American. “My generation turned a blind eye to the system,” says Goodluck, now part of that 1 percent of Native American authors of children’s books, with her sixth and seventh titles sold. “It’s like we didn’t see ourselves for decades and decades. And we just accepted it.”

But the payoffs for Native American children when they see themselves, their foods, their families and languages represented in books they find in their school or a library are immense, Goodluck says.

“Oh, gosh,” she says. “They feel valued. They feel seen. They feel treasured. All the things that all kids feel when they see themselves in books as a hero of a story solving problems and critically thinking. As their identities are forming, books can be a source that makes them feel proud and stand tall.”

After graduating from UNM, Goodluck worked at several nonprofits, including Futures for Children and the New Mexico Family Network. She took some time off to raise her sons and then spent a decade managing her husband’s medical practice.

When her oldest son was graduating from college in New York City, Goodluck visited and they went to two museum exhibits that changed the course of her career. One, at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, featured the work of three generations of Inuit women who created prints and drawings of village life, rich with celebration and joy, but also with a critical eye toward modernity and its effects on Inuit culture. “Part of their theme was to tell people we’re still here in this modern world,” Goodluck says. “I was really struck by that because I’d been so caught up in my work in medical administration that I kind of forgot that, yeah, we do still need to tell people that our people are still here and living in this modern world.”

Then, they went to the Studio Museum in Harlem and saw an exhibit of picture books written and illustrated by members of the black community depicting their modern lives in their own voices and lived experiences. The art and stories were vibrant and beautiful, and she was in awe. “I had never seen picture books or children’s books like that before, books that were written by black authors and illustrators representing their own communities. And by the time I got home, I was like, maybe I can do this,” she says. “So that’s when it began.”

Book publishing traditionally is a white industry famously closed to diverse writers and illustrators. And Goodluck had never written a book.

She began to research what makes a successful kid’s book, how to build characters and tell stories. Her online research led her to the nonprofit organization We Need Diverse Books, which advocates for diversity in publishing in terms of authors and subject matter, and everything clicked. “I thought, ‘They’re playing my music,’” Goodluck recalls.

The organization has conferences and mentorship programs for published and aspiring authors.

Goodluck missed a deadline for the mentorship program, which gave her another year to practice and grow. The following year, 2019, she was accepted and paired with Traci Sorell, a Cherokee author who lives in Oklahoma.

Sorell, the former director of the National Indian Council on Aging in Albuquerque, met Goodluck when she came back to Albuquerque for the launch of her own children’s book. When Goodluck applied to become a mentor the next year, Sorell liked Goodluck’s subject matter and drive. “I knew if she was willing to do the work, she could definitely get where she wanted to go,” Sorell says. “And she absolutely was.”

Sorell worked with Goodluck on the unique craft of writing a children’s book, which usually runs no more than 500 words and uses illustrations to tell large parts of the story. And, as importantly, she taught her how to navigate the system of conferences and grants for Native writers. Sorell also sent her out to the library to study recently published picture books and then asked her to drill down to what kinds of stories she wanted to tell.

“She really focused, concentrated, made time, which was not easy given that, you know, she’s balancing having her day job managing her husband’s medical practice and trying to nurture this creative career,” Sorell says. “And by the end of our year together she had an agent and was selling manuscripts.”

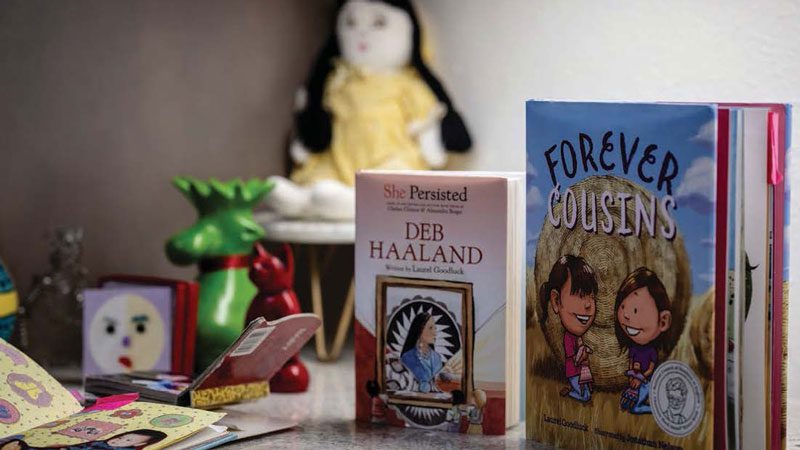

Meanwhile, Goodluck also expanded and found her community of Native writers. At one conference, Goodluck connected with a cadre of Native writers who stayed in touch on Facebook after the conference ended and developed a critique and support group that helped her give birth to her first book “Forever Cousins,” which she sold to Charlesbridge publishers in 2020.

It tells the story of two cousins who fear their bond will be ruined when one moves with her family back to the reservation. It’s a universal theme of love, family and friendship, sprinkled with Indigenous culture. At the back of the book, the author’s note is where Goodluck likes to explain the inspiration for the story and the erased Indigenous history not told in the United States educational system. In “Forever Cousins,” she writes about the Indian Relocation Act that brought her parents and other Native people to the cities in an unjust assimilation program.

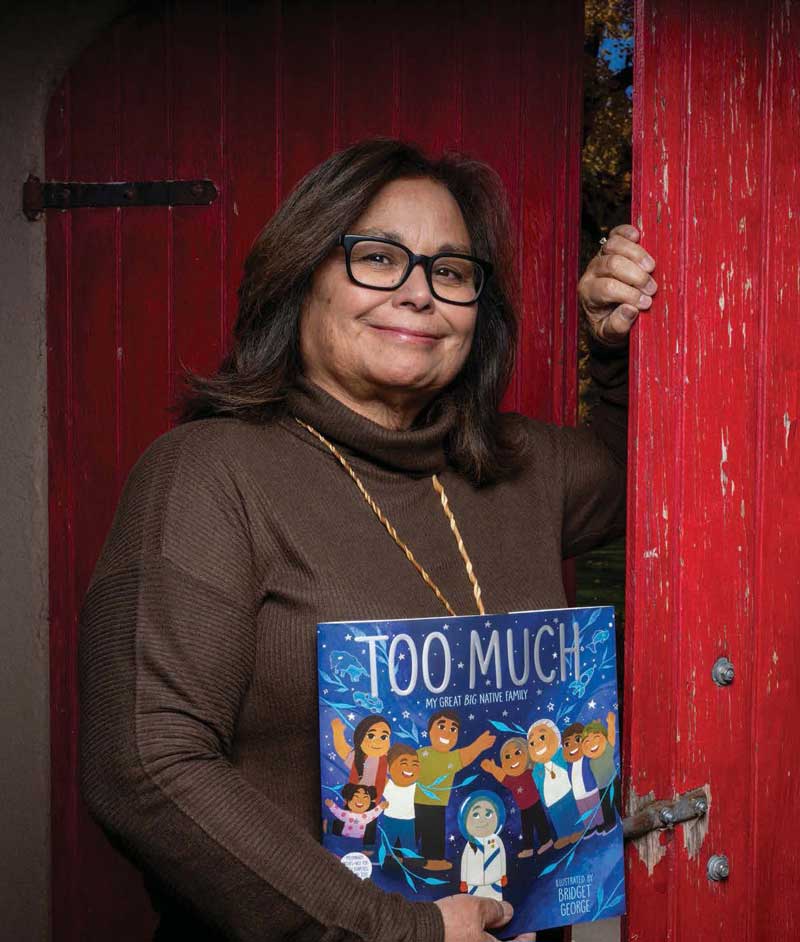

Laurel Goodluck with one of her many children’s books.

“They feel valued. They see feel seen. They feel treasured. All the things that all kids feel when they see themselves in books as a hero of a story solving problems and critically thinking. As their identities are forming, books can be a source that makes them feel proud and stand tall.”

While others baked sourdough and banana bread during the COVID-19 pandemic, Goodluck was impressively productive. She wrote and sold three books to three major publishers.

“Forever Cousins” was published in 2022; “Rock Your Mocs” was published by HarperCollins’ Heartdrum imprint in 2023; “She Persisted: Deb Haaland,” a chapter book for young readers, was published by the Penguin Random House Philomel Books imprint in 2023.

Kevin (BS ’86, MD ’94) who met his future wife at the Kiva Club at UNM, closed his medical practice during the pandemic, which allowed Goodluck to concentrate on writing.

Her latest books are “Too Much: My Great Big Native Family,” published by Simon & Schuster, due out in 2024. “Fierce Aunties,” published by Simon & Schuster’s Simon Kids imprint, and “Yáadilá! (Good Grief!),” published by Heartdrum, both due out in 2025. “Stories Are the Heart of the World,” which Goodluck calls “a love letter to my sons,” is due out in 2026.

It’s quite a feat for a novice writer who never pursued an MFA. She started to learn to write when she was 56, had her first book published when she was 60 and, at 61, is now a mentor to other writers.

Goodluck looks to her upbringing to help explain her success.

“I grew up hearing oral storytelling,” Goodluck says. “And that tradition of learning about my people’s struggles and legacy through these stories really did help me as I began to learn this industry and ask what I can do to give that to kids in a new way, a new form, so that they can rely on their culture that they can be resilient and strong.”

For young Native readers, Goodluck’s goal is simple: “That they can see their culture like a superpower that they can rely on and be their whole selves.”

For non-Native readers, she aims to dispel stereotypes, for example Native people portrayed in children’s literature as caricatures wearing feathers and warpaint, by depicting Native people living in the real modern world. “I guess I hope that they get that their world is bigger than what they know that they open up their world the same way my world was opened up when I would go traveling as a kid and see other people in different cultures and the way they lived,” Goodluck says. “I think when they’re young, they have their mind wide open. And then they kind of lose that; it gets closed up. So that’s another reason for writing for young people is having an impact on them on a young age.”

Goodluck continues to write and is now a mentor herself to a new crop of Native writers.

“I am just ecstatic to see not just the things that she has put out in the world, but all the things that are to come,” Sorell says. “She is absolutely one of the most beautiful, giving, creative souls, so having her sharing stories with young people is wonderful and with her mentoring she is now bringing more people from underrepresented communities and marginalized voices into the industry, which is exactly what we need.“

Story by Leslie Linthicum Photos by Roberto E. Rosales

In his memoir, “Running Dreams,” Servan recalls the moment on that patrol that his old life — young and on a path to a career in police work in his native Peru — abruptly ended and the long and difficult journey began to a new life he never would have imagined.

“My right boot brushed up against something. The object, about the size of my fist, felt different somehow, lighter than I would have thought for a rock. I picked it up. Its mud- encrusted, rusty surface looked as if it had been shot through by bullets. Suddenly, it exploded in my right hand.”

In the hospital, his head bandaged and on strong pain killers, Servan waited to be told the extent of his injuries. Every night he inched his aching left hand a little closer to his right until he finally could reach across his body and realize his worst fear. His right hand was gone.

Today, at 57, Servan remembers a moment he had as a 20-year-old, on vacation from the detective training academy. He was poolside, taking in the beautiful flowers and the beautiful girls.

“I’m thinking, ‘So OK, I’m getting ready to become a detective. I might be exposed to fighting and I might lose my legs. I could be okay. And then I could maybe lose my arms. I would be OK. And then I could become deaf. I’ll be fine; I can still do everything else. And then I thought, what if I become blind?’ And I didn’t want to think about it. No, no, that would be too bad. I don’t want to think about it.”

When the bandages came off his face, Servan was blind. He had lost his right eye, and surgery to restore the vision in his left eye was unsuccessful.

Servan is on the phone from Burlington, Vt., where he is attending a conference on the importance of data in vocational rehabilitation.

As the executive director of the Nebraska Commission for the Blind and Visually Impaired, Servan travels frequently.

He wonders whether his poolside ruminations about blindness were a foreshadowing of his destiny or just the idle thoughts of a young man about to embark on a life of adventure. But he realizes he was right about one thing — blindness has been harder to overcome than losing a hand.

“The misconceptions about blindness, the awkward way people would treat me even though I was the same person, that was the hardest to overcome, especially at the beginning,” Servan says.

His career in policing came to an end, as did the hobby he was passionate about — running. His girlfriend left him. It was a depressing time, especially for a young man who was intent on finding a rewarding career.

“There’s this idea that there’s a lane for blind people to stay in and the sort of jobs would be expected,” Servan says. Helpful and well-meaning people suggested massage therapy, telephone operator, musician.

“In the back of my mind, I knew I could do something, you know?”

Servan’s father died of a heart attack while he was away at training. But as his son was growing up, he offered what would become prescient advice. “It is not the circumstances of birth that make a man; it is what he makes of himself. You will have ups and downs, but your strength of character will show as you get up after every fall.”

Carlos Servan earned three degrees from UNM after losing his sight.

In Peru, Servan had learned the basics of the Braille code and how to walk with a cane. As he was living in Baltimore with his mother along to help him, Servan began to take English as a Second Language classes and found a sponsor for his application to immigration services to stay in the United States.

Because Spanish was his first language, Servan was sent to New Mexico to continue his training. In Alamogordo, Servan was immersed in learning how to live independently without sight.

“The skills of blindness have to do with learning and embracing the Braille system and learning how to get around in all situations with the white cane,” Servan says. Doing your own shopping, cooking, using the stove. Not just the basics, but mastering them.”

After he finished the course at Alamogordo, Servan moved to Albuquerque and continued to learn English. When he thought he was ready, he applied to UNM.

“It was a big challenge,” Servan says, learning how to navigate the campus, find his classrooms and get his reading materials on tape. He learned to type his papers with one hand.

“I guess I got good training in Alamogordo, because once I knew where my classes were, it was easy,” Servan says. He likes navigating in crowded spaces. “When there are a lot of people in a place, it’s easier for a blind person because if you get

confused, you can ask anybody. And you can listen to the footsteps, where people are going, when people turn to the left or to the right. You can hear when people go upstairs.”

Servan got his BA in political science in 1993 and for a second time was accepted into law school. At UNM he studied law while also pursuing a master’s degree in public administration. With an MPA in 1995 and JD in 1997, Servan was ready to work in the field he had come to know and respect — services for the blind.

He was hired as the deputy director of the Nebraska Commission for the Blind and Visually Impaired and in 2017 became the agency’s executive director. Like the New Mexico Commission for the Blind, which helped Servan get his footing when he first landed in Albuquerque, the Nebraska commission offers independent living and vocational rehabilitation to help blind people, like Servan did, pursue their chosen career fields.

Servan has always advocated for full immersion of the blind in life. too. “You know, when I talk to people here, they usually just want to settle for jobs or benefits that will only take care of them. I say, ‘You can do more.

You can own your own house, you can go on vacation, you can have money for your retirement. And not only that, but you just feel productive.’”

Servan has also seen a change in younger blind people, especially those who have come of age since the adoption of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

“So the blind folks in my generation, we never thought the world would change for us. We thought we have to do everything for ourselves,” Servan says. “But after the ADA, the new generation, they say, ‘Wait a minute, I have the right. You better make this accessible.’

They’re more assertive and that’s good.”

Greg Trapp (’87 BA, ’90 JD) met Servan in the late 1980s on a bus trip to a National Federation of the Blind conference in Denver. Trapp was finishing law school, Servan was thinking of applying and, even though Servan still struggled with English, the two hit it off.

“Kind of kindred souls, kindred travelers,” says Trapp, who is executive director of the New Mexico Commission for the Blind.

“The skills of blindness have to do with learning and embracing the Braille system and learning how to get around in all situations with the white cane.”

They remained friends and colleagues and Trapp has been impressed by Servan’s fortitude. “He was able to overcome both the blindness and the physical disability and also the language barrier,” he says. “He really is a leader in our field and he has accomplished a tremendous amount in his life and a lot of blind people have benefited from his work.”

They spend time together regularly as they travel to conventions — Trapp was president of the National Council of State Agencies of the Blind in 2007 and Servan just finished his term as president — and before Trapp was married, he liked to take advantage of Servan’s charisma and Latin accent to meet women.

“We would go to the hotel bar and I would say, ‘Carlos, start talking.’”

Servan began his latest vocation — author — only as a way for him to review the astounding events of his life. As he wrote he began to think he might have a story that could help or inspire others and he eventually found a publisher who brought the memoir to bookstores. Of course, it’s on Audible as well.

As to the ending of Servan’s story, it is not yet in its final chapter. He has exciting innovations in the works in Nebraska, including developing equipment that will help high school and college students do laboratory science independently and using

a 3D printer so blind people can name something they would like to experience — say the artery system of the heart — and have it quickly in their hands.

He ended up marrying Catalina, the woman he began dating after his injury. They have four children — all graduated from college and several in graduate school. His mother settled in Albuquerque and his siblings live there today.

As for running, Servan still does. He takes to a bike path in Lincoln with a partner, one of his children or a colleague, holding one end of his cane and running a step or two ahead of him.

Also, Servan jokes, he walks so fast with his cane that maybe running isn’t even necessary.

“Blindness, it’s just part of my life,” Servan says. “Obviously I have challenges, but we all do in parts of our life.”

Recent Comments