A Career in Flight

Engineer Thomas H. Gray (BSEE ‘61) helped Boeing aircraft fly right

By Amanda Gardner

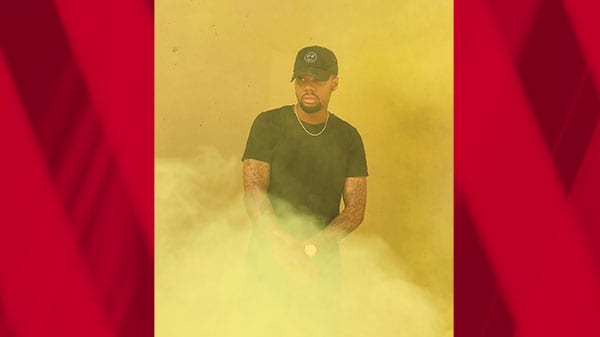

Thomas Gray’s life story is equally the story of modern air travel. During his 34-year career with The Boeing Company, Gray, who graduated from UNM with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1961, was a flight test engineer on almost every Boeing commercial aircraft, from the 707 through the 767. In February 1969, he also became the first nonpilot to fly on the first 747, when the new jet took flight from its birthplace in Everett, Wash., to Seattle.

Transportation is in Gray’s blood. Both his father and his grandfather worked on the railroad, his father as a porter for the Pullman Company on the fabled Santa Fe Super Chief running from Chicago to L.A.

At Pullman, porters made beds and did housekeeping in the sleeper cars, often catering to Hollywood stars making their way across the country.

On other rail lines, Black brakemen like Gray’s grandfather were also known as porters.

His grandmother and mother sold box lunches to train travelers stopping in Albuquerque who couldn’t afford the local Fred Harvey restaurant. That’s how his mother met Gray ’s father.

Gray’s own love affair with transportation began long before he entered UNM. Growing up off Lead and Broadway, he was not only next to the train tracks, but he was also not far from Kirtland Air Force Base. As troops mobilized to fight in World War II, “I watched all the planes going off to war from the end of Kirtland’s runway,” he remembers.

After graduating from Albuquerque High School, Gray enrolled at UNM. He was one of only a few Black students at a time when UNM had just started recruiting Black football players, including his friends Don Perkins (’60 BA), who became a running back for the Dallas Cowboys, and Edward Lewis (’64 BA, ’66 MA), who went on to co-found Essence Magazine.

During the summers, Gray worked as a chair car attendant on the Santa Fe Railroad Superliners, the El Capitan and the Chief.

Gray joined the New Mexico Air National Guard before his UNM graduation and later transferred and served in the Washington State Air National Guard when he moved to Seattle.

Boeing recruited Gray soon after he graduated from UNM at “the ground floor of the Jet Age,” he recalls. His job was to design and install instrumentation equipment required to monitor and record all the aircraft parameters involved in flight testing each new aircraft model. As a flight test engineer and crew member his role was to monitor and tape record in flight the data from multiple sensors spread all over the aircraft to measure data — aerodynamic performance such as airspeed, altitude and control surface positions — not normally collected on a production version of the same aircraft.

In the mid 1960s Gray was loaned out to the Advanced Marine Systems organization to work on the instrumentation in Boeing’s jet-powered research hydrofoil, which involved test runs up and down Puget Sound. Gray found that flying a wing under water was quite different than an airfoil in the atmosphere.

He returned to the Commercial Aviation Division when Boeing started flight testing the first 737 aircraft in 1966 which was followed by the 747, 757 and 767 programs.

Over the years, flight testing has changed. “On the first 747, we had 700 measurements to evaluate the aircraft performance,” he says. Today, flight test engineers are able to record and study some 20,000 different measurements due to advances in digital and computer technology.

Along with Boeing and the rest of the world, Gray then joined the Space Age. In 1977, Gray participated in the space shuttle Enterprise landing tests at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

“With the Space Shuttle development, engineers came up with a plan to carry and launch the shuttle from atop a 747,” he remembers. “We actually put our test equipment in the 747 carrier aircraft and Boeing structural engineers and mechanics reinforced the top of the 747 to carry the weight of the shuttle.”

Over the years, Gray has brushed with fame and history, having been on a test program on the airplane that became the Air Force One that flew President John F. Kennedy to Dallas and where Lyndon B. Johnson took the oath of office after JFK’s assassination there. He had been on flight tests with space shuttle astronauts Dick Scobee, Judy Resnik and Sally Ride.

He even flew a 747 once — holding the controls for four minutes while the pilot stepped away to use the restroom.

Gray says he was never nervous taking jets up for their first flights, and all of his test flights went off without a hitch, except one — on July 5, 1974, when he was doing brake testing on a new 747 aircraft at Edwards Air Force Base.

“The test requirements were to do what is called a ‘refused takeoff’,” he says. “The pilot gets the fully fueled 747 up to takeoff speed and then uses the brakes to bring the airplane to a full stop on the runway.”

Due to the high energy stop, the fiery brakes disintegrated, and the 16 tires started exploding and burning. “That gets your attention really quick when you’re sitting at a monitor station in the middle of the aircraft,” Gray recalls.

Gray used the emergency escape ladder while tire debris was still flying around him. In the commotion he missed the bottom ladder rungs, which resulted in a brief hospital stay. Fortunately, no bones were broken. “Flying on test airplanes was a lot safer,” he says.

Gray retired in 1995 and is now a docent at the Seattle Museum of Flight and a member of the Sam Bruce Chapter of Tuskegee Airmen, Inc., an organization that preserves the heritage of the original Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. He and his wife, Nyra, have two sons and two grandchildren.

One thing that hasn’t changed is Gray’s commitment to UNM, which he calls his “neighborhood school.” This is reflected in his contributions to the Electrical & Computer Engineering Department and his service as a past president of the Seattle Chapter and past board member of the UNM Alumni Association.

“He’s from New Mexico no matter where he is,” Nyra says.

Recent Comments