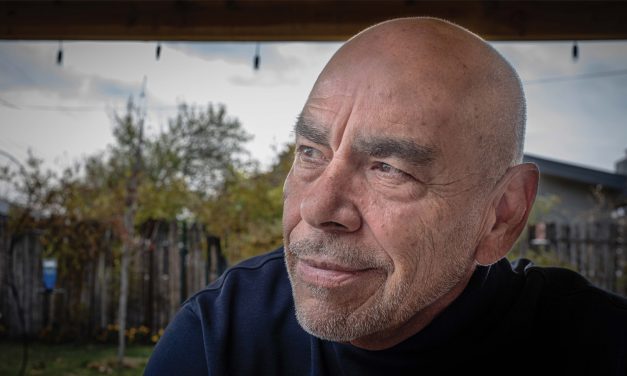

Photos: Tom Lazarevich

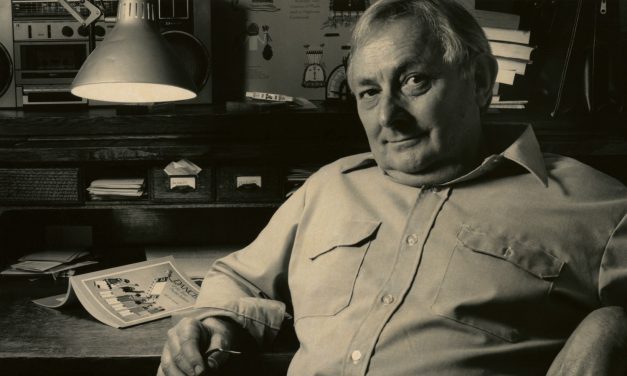

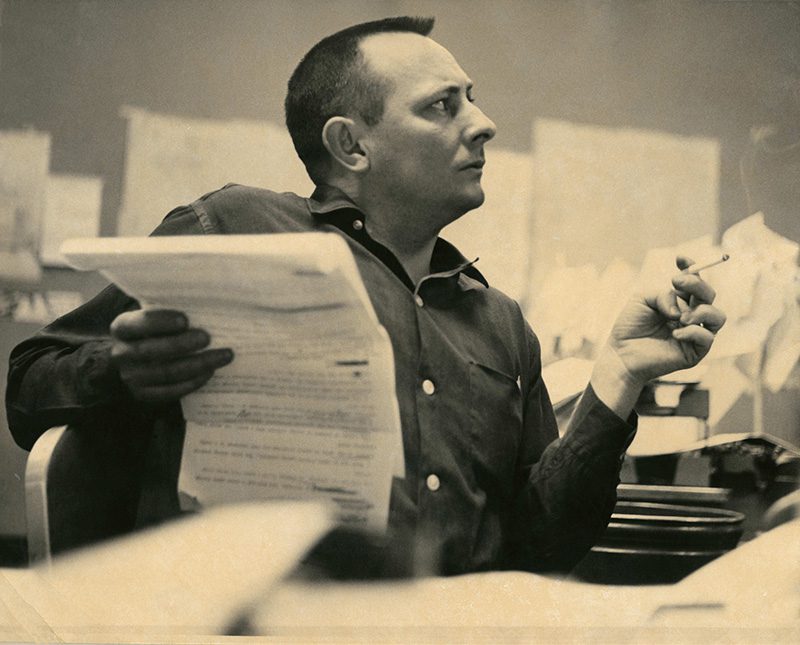

Tony Hillerman (’66 MA), who died in 2008, was a distinguished alumnus with an international reputation for his page-turning mystery series set in the Indian County of the Southwest. He was also a popular professor at UNM who taught a generation of students how to write.

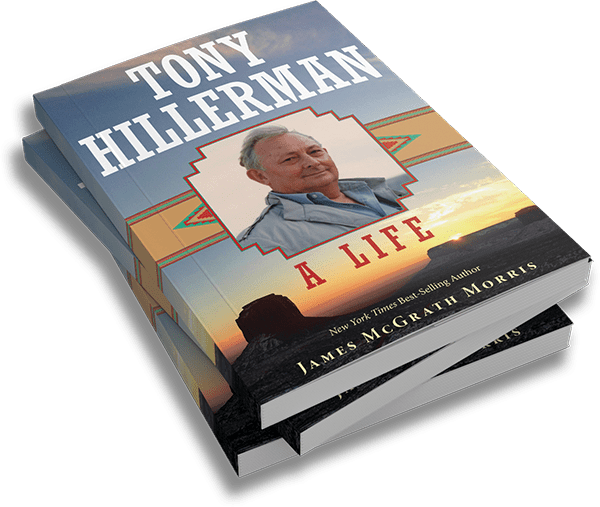

In a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM and the publisher, University of Oklahoma Press, allowed us to reprint it here.

Professor Hillerman

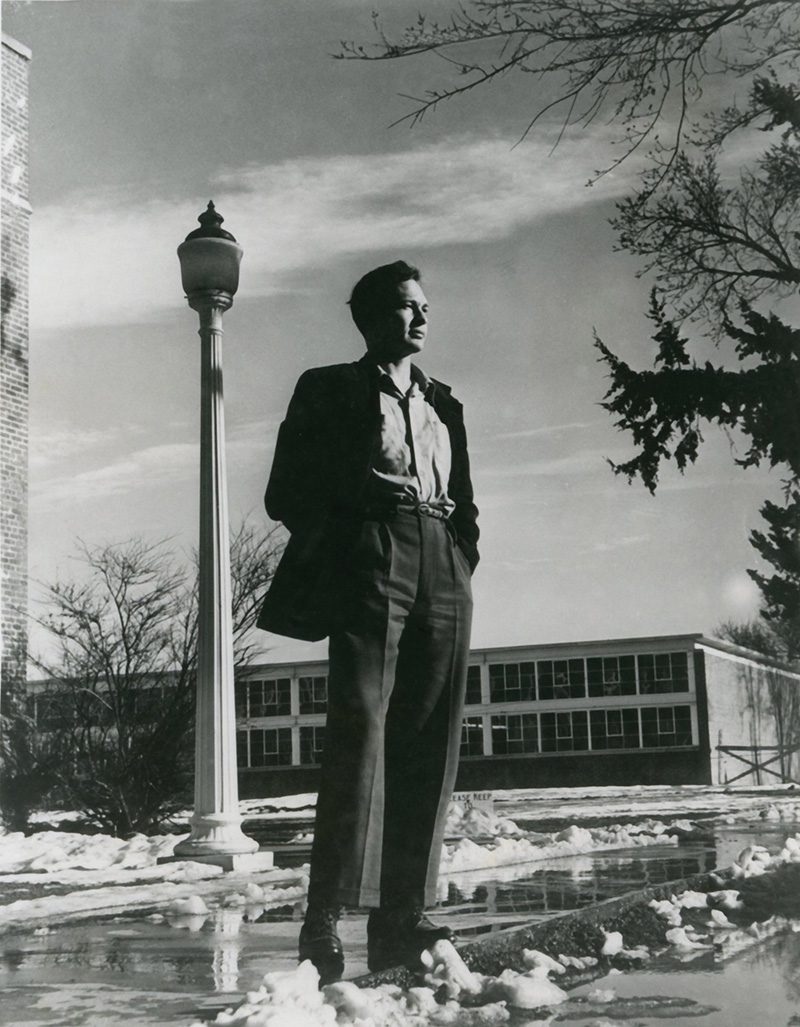

The thermometer read ten degrees the morning Tony Hillerman drove to campus for the first day of the spring semester, January 5, 1970. He steered his dark-metallic-green 1970 Ford Maverick — the first new car he had ever owned — down Louisiana Boulevard to Interstate 40. When the smog above Albuquerque abated, the place offered Hillerman an expansive view westward. “It is exactly at this spot and at this moment that Mount Taylor comes into view,” he said. “It is my favorite mountain, and the gateway to my favorite places.”

To most commuters, the panoramic vista was just one more in a state filled with geographic splendor. But to Hillerman the view of the mountain now took on a meaning shaped by four years of studying Navajo culture. Tsoodził, as the Navajos called it, was one of the four sacred peaks delineating the boundaries of Dinétah, the Navajo homeland. To the north and west of Tsoodził lay the land that had served as the setting for the novel waiting to go to press in New York. “My map tells me the Turquoise Mountain is 62.7 miles from this noisy intersection,” said Hillerman. “In another sense the distance is infinite.”

The day would afford little opportunity to think about that distant land or his book. Students were streaming back onto the campus. Enrollment in the Journalism Department had grown by 20 percent during the last year. Hillerman had to prepare for three courses: Advanced Reporting, Newspaper Practice, and Media as a Social Force. In addition, he was planning for a new course in editorial writing in the fall and had tedious administrative responsibilities as department chair. His office was on the southern edge of the campus in one of the university’s ubiquitous adobe buildings that had once served as a residence for women students.

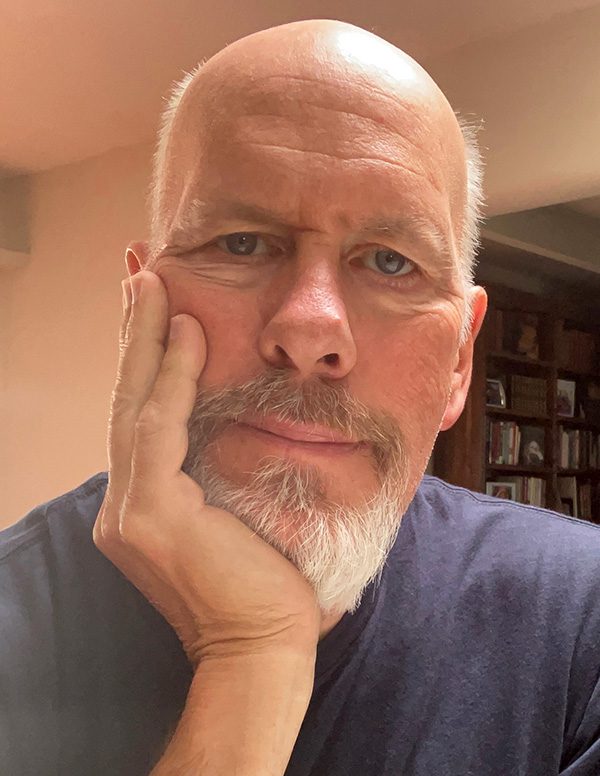

James McGrath Morris

Hillerman usually arrived on campus in an ebullient mood. “Have you seen the clouds today?” he would ask Mary Dudley, who worked briefly in the office. “If I didn’t give a convincing yes,” she recalled, “he would insist that we go out and we’d stand on the lawn of the Journalism Building and look at the clouds come over the Sandia Mountains.” Ever since he was a child growing up in Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl. Hillerman had been a cloud watcher.

When Hillerman had first begun teaching at UNM four years earlier, he had inherited the basic journalism classes such as News Writing. Instructing future journalists harkened him back to his days as a student at the University of Oklahoma after the war. “It was a wonderful time to be teaching,” said Hillerman. The students struck him as eager to learn and they took to his folksy pedagogy. The avuncular professor wore the narrow ties that were fashionable then, but loose with an open collar, with jackets and pants carelessly matched. “There’s none of the professorial moss about Tony,” noted a reporter who stopped by the campus that spring. “There is a disarmingly casual air about him.”

In class, students were treated to tales from the trenches of daily journalism. “He was always warm, humorous, generous, droll, with an anecdotal style of teaching, using lots of illuminating examples, many from his own experience,” according to former student Sharon Niederman, who became an author and journalist. Hillerman’s recollections were his tools of teaching, journalistic parables that also served to inspire. “We wanted to get out in the world and turn experience into prose,” said another former student, George Johnson.

Like the much-admired Professor H. H. Herbert at the University of Oklahoma, Hillerman wanted his students to understand the power and the accompanying responsibilities that came with being a reporter. “From him, the students learned about real-life examples of proper journalism ethics,” recalled one student. Hillerman was not averse to using his own experiences to show the consequences, often unforeseen, of the news business. The topic was also on his mind in the 1970 spring semester. In his typewriter at home was the beginnings of a new novel in which journalistic ethics would play an important role.

Inspired by William Strunk Jr and E. B. White’s The Elements of Style, Hillerman offered a set of writing rules to guide the willing students. At home, he was putting them into practice in his fiction. “Writing is writing,” Hillerman told his students. “Whether fiction or non-fiction, poetry or prose, most of the same rules apply, most of the same devices are effective, most of the same flaws will kill you.”

Concision was paramount: “As sentences get shorter, they generally get stronger,” he said, paraphrasing the famous guide to writing. Active voice should be a habit: “It makes for forceful writing.” Concrete and specific nouns and verbs were preferable: A welder rather than a laborer, a begonia instead of a flower. Echoing the instructions to remove “cornstarch words” that Professor Grace Ray had given when he was in college, Hillerman offered his students a lesson in wordectomy. The sentence “The animals’ faces expressed pleasure as they consumed their food” became concise, concrete, specific, and active when written as “The hippos grinned as they chewed their carrots.” For Hillerman, writers were verbose because they lacked a command of the vocabulary. Conciseness does not demand short sentences, he said, “It requires simply that every word tell.”

The placement of words and clauses should be deliberate: “Use the phrase, or word, you wish to emphasize, at the end of the sentence or paragraph.” Also, a word or clause gains attention if used at the beginning of a sentence when it is not the expected subject. For instance, “Bad manners, she could never tolerate” or “Reckless drivers, these Armenians.” Writing with nouns and verbs achieved economy: the elderly man walked slowly by is made better by using the word plodded. “When you use adjectives choose them carefully,” he admonished. “If you pick the right noun or verb you probably won’t need them.”

Hillerman pushed his students to make their writing reveal rather than tell and to weave their material together. In his class on persuasive writing, aspiring journalist Susan Walton struggled at first with shedding the linear way she had been taught to write. “I wasn’t synthesizing well. I was really regurgitating,” she said. “And he wasn’t interested in that. He wanted to see a process of consideration and thought, coming out.” He pushed the students to use observations to develop a point of view. Drawing on his experience writing editorials at the Santa Fe New Mexican, Hillerman demonstrated his method. If, for instance, city maintenance was failing, Hillerman figuratively walked the reader down the street to the fence lined with trash, by the drain with cockroaches, and past the unfilled pothole. Now that he was a professor, he instructed his students to leave campus to hone their observation skills.

Compare the crowds at the airport and bus terminal, he told them. “If you think they represent different socio-economic classes, let me see enough to lead me to the same conclusion.” Visit bars frequented by homosexuals and a bar playing country-western music. “What do you see that identifies them?” Attend a trial and look for a bored member of the jury. “Show me what you saw that caused you to think that.” Hillerman argued observation and detail were the keys to a good journalistic story, according to one student. “Hone in on every detail so that you could set a stage around a story.” If the stories the students brought back were good enough, Hillerman offered them to the Albuquerque Journal, which occasionally published some.

Papers assigned are papers in need of a grade. When it came to the many essays and articles submitted by his students, Hillerman applied an idiosyncratic approach. He evaluated the students’ work on a ten-point scale and was not hesitant to provide an opinionated reaction, though gentle in his criticism and invariably encouraging. One of his talented students, George Johnson, broke up with this girlfriend just before the final assignment of the semester was due. “I was up late drinking beer and spewing out pages of typewritten angst, which I submitted the next morning.” Hillerman returned the work with an A+. “You write better drunk than most students do sober,” he wrote on the top of the paper. “That was all the encouragement I needed,” said Johnson, who went on to become a New York Times editor, science reporter, and author.

On major assignments students received lengthy typed evaluations. For instance, Hillerman wrote a one-page, single-spaced commentary praising and encouraging a young woman who had submitted chapters of a novel in a creative writing class he taught. “None of this has anything to do with the grade,” he wrote. He explained that she came to the class with a lot of talent and some bad habits and left with a lot of talent and some progress. “I rate that as Satisfactory Performance which earns you a C,” he concluded. “Had I been a better teacher for you it could have been a B at least.” To another student named Felipe, he wrote, “I think I will give you a B, which reflects a grade but not my judgment of your talent, which is remarkable.”

His dedication to his students prompted him to spend time selecting paragraphs from their work, typing them up on a stencil, and running them off on the office mimeograph machine. The blue-inked sheets were then distributed in class for group discussion. Typically, Hillerman Socratically pushed the students to apply his writing rules. “You say ‘obviously drunk,’” he might say, “What made it obvious?” Along with samples of their own work, Hillerman typed up more stencils with brief excerpts from the works of Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Gary Wills, Barbara Goldsmith, Ken Kesey, and Gay Talese, among others.

Hillerman was certain he could teach most of his students to write. “There are some who can’t be taught to write,” he admitted, “just as I can’t be taught to whistle thru my teeth.” He disliked many of the bromides about the craft. It was, for instance, “sheer nonsense” that writers write for themselves. “You have to write for someone otherwise you’re like a man at a telegraph key talking into a vacuum. It’s totally sterile and self-defeating,” said Hillerman. The point is to send and receive, “translating,” in his words, “the image inside your skull into symbols and launching it at a target.”

Teaching nonfiction while exploring the writing of fiction after-hours caused Hillerman to reflect considerably on the differences between the two. “The differences between fiction and non-fiction are more apparent than real,” he wrote. Nonfiction, which he had been trained to write and now taught, was less pliable than fiction and more craft-like. Fiction demanded more creativity resting on material either made up or from one’s memory. “The facts are crafted in your imagination,” Hillerman said. “They are glossy, persuasive, rich in symbolism, redolent of universal meaning, glittery, sordid, perfect, polished facts — the stuff of art.”

Despite the demands of being department chair and the late-evening hours consumed by his own writing, Hillerman always made time for students. He wanted to provide instruction on how to write but give encouragement as well, as Professor Morris Freedman had done for him. “He himself was an author, which impressed me,” said Hillerman, “and he saw promise in my work — which impressed me even more.”

Jim Belshaw was one of many aspiring journalists who experienced Hillerman’s devotion to students. After being discharged from the Air Force, Belshaw registered for classes at UNM in September 1970. The clerk handed him a small slip of paper with the name of his adviser. “I looked at the name and thought, well, I don’t know who Tony Hillerman is, but I know how to report.” When he reached Hillerman’s office, the professor looked over Belshaw’s test scores, particularly the ones for math. “Journalism, right?” asked Hillerman.

Hillerman guided Belshaw to an undergraduate degree in journalism and on to a career as a reporter and columnist. While working at one of his first jobs on a Las Cruces newspaper, Belshaw sent his former professor the manuscript of a book that had been rejected by a publisher. “The reason you sent it to me is because you lack confidence,” Hillerman wrote back. “Go to the library and pick any novel (not the great classics) and read it. You will find that you write as well as most, and better than some.”

Once Judy Redman stopped by his office. Hillerman was her adviser and she wanted to show him a creative writing paper on which she had earned an A. Another professor overheard the conversation and stuck his head in the door. He jocularly told Hillerman that students studying creative writing in the English Department will hurt their ability to do journalism. “I disagree,” replied Hillerman. “Good writing is good writing.” Redman went on to become a reporter and book author.

Hillerman, however, believed journalism was the best training ground. Carmella Padilla, a Santa Fe native, was uncertain what career she might want to pursue when Hillerman asked her about her goals. “I was thinking I wanted to be a physical therapist,” she recalled telling him, “but I don’t know, maybe I want to major in English.”

“Yeah, but what do you want to do?” persisted Hillerman.

“I want to write, I think.”

“Or do you want to teach?”

“Well, I think writing is more becoming to me than teaching.”

If that were the case, Hillerman advised her to stay clear of the English Department. He continued, according to Padilla, to say something to the effect: “If you really want to learn how to write, and learn the discipline of writing, which is what it’s all about, you’d be better off in the Journalism Department.”

“That really sunk in. I won’t be so bold as to say that Tony Hillerman directed me to be a journalist, but he certainly opened my eyes to that as an option. After completing the journalism program, Carmella Padilla became one of New Mexico’s most distinguished authors and an editor of work devoted to the Hispanic art, culture, and history of the state.

The dedication Hillerman showed his students, his willingness to guide them, and his irrepressible and engaging classroom storytelling made him an immensely popular professor. One student, however, ran up against a unique problem taking one of his classes. His daughter, Anne, made the mistake of enrolling in her father’s early-morning class. Her eyelids grew heavy and she dozed off to the sound of the voice that had once put her to sleep reading bedtime stories.

Spring 2022 Mirage Magazine Features

Big League

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

Read MoreFrom Prison to Poet

University of New Mexico alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca found peace in the written word…

Read MoreProfessor Hillerman

In a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM…

Read MoreForm and Function

Among campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, UNM has always been distinctly of New Mexico…

Read MorePicture Perfect

You can thank an alumnus for creating the image technology that keeps us connected…

Read MoreMy Alumni Story: Joshua Whitman

When I decided to attend UNM I applied to live on campus because I wanted to become involved in student life…

Read More