Photos:

Roberto E. Rosales (’96 BFA, ’14 MA)

UNM grad helps spark electric vehicle revolution

In A Solid State

By Leslie Linthicum

When Doug Campbell was a skater punk in Albuquerque in the 1980s, The University of New Mexico campus was his skate park. Unfocused in school and happy to buck authority, he rode the ramps and sidewalks of campus, one step ahead of the university police.

Campbell went on to earn two degrees from UNM, a bachelor’s in civil engineering in 2001 and master’s a year later, and took several classes from Gerald May, who happened to have been the president of UNM when Campbell was getting chased off campus by UNM police.

Well, no hard feelings on either side.

Campbell had finished his bachelor’s and was unenthused about the traditional career paths for a civil engineer. As Campbell’s undergraduate advisor, May saw a saw a young man struggling to figure out his future.

“He was one of those students who was driven, exceptionally bright. He was focused,” May says. “And he was restless, in the sense of wanting to do more.”

“Doug,” May told him, “you’re destined for great things, but if you can’t decide what you want to be, go to graduate school and you’ll better see your path.”

“And,” May says today, “he did.”

In graduate school, Campbell found his passion in aerospace and in solving complex problems.

Today, he is an entrepreneur who sold an aerospace startup two years ago and is CEO of a next-generation battery company that has deals with Ford and BMW.

Blessed by his success, Campbell just donated $5 million to the School of Engineering, earmarked for the Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering. The gift is without restrictions except for one: The department will be named for May.

When he made the gift and specified the department be named for May, Campbell wanted to honor a man who helped change his life.

“He is such a phenomenal individual,” Campbell says. “He was such a humble and phenomenal teacher. I just developed an immense amount of respect for him.”

Finding the Path

Campbell, who splits his time between Longmont, on the Colorado Front Range, and Gunnison, on Colorado’s Western Slope, has arrived in Albuquerque to look for an apartment for his eldest son, Ethan, who begins UNM as a transfer student this year. He drove down from Boulder County in his Porsche Taycan, a sleek rocket of an EV that can get to 60 in three and a half seconds. “Amazing,” is Campbell’s assessment of his electric ride.

Not yet 50 and with a startup cash-out behind him and another one in the high-stakes and lucrative race for the best EV battery technology, Campbell could be one of those arrogant Silicon Valley tech bros he likes to call an unprintable name.

Instead, he’s casual and funny, ready to tell an embarrassing story on himself (his personal website is www.entrepreneurialdysfunction.com and he describes himself as a battery nerd) and just as ready to admit to the luck that’s got him to where he is today.

“There’s always luck,” Campbell says. “But I also saw that we as a society are moving toward an electrified future.”

Campbell’s parents met at St. Pius High School in Albuquerque and Campbell was born in Mountain View, Calif., where his father was stationed in the Navy. His mother, Mary, was 18 when she gave birth and shortly after found herself divorced and back in Albuquerque.

Until she married Campbell’s stepdad when he was 10, “She was a single mom and basically said, ‘I gotta do something with my life,’” Campbell recalls. “And she went to UNM and got a degree in civil engineering. I grew up on campus. I would putz around and go to the

Duck Pond. She would take me to school and say, ‘I gotta go to class; entertain yourself.’”

His mother, who died in 2006, was one of the reasons Campbell chose to study engineering when he finally enrolled in UNM in his mid 20s.

His path to college was anything but traditional and that has a lot to do with hormones.

“Pre-puberty Doug was very active, very athletic,” Campbell says. “Post-puberty Doug was a shitshow. Always in trouble. Causing hell. Very anti-authority.”

Campbell barely got through Albuquerque High School and didn’t even consider going to college. Luckily, he found the sport of mountain biking and managed to get very good at it.

He turned pro in 1997 and spent the remainder of the decade racing all over the country on the national circuit. As he focused and matured, Campbell started taking some courses at what is now Central New Mexico Community College. His last full-time racing season was 1999, when Campbell, then 26, realized he needed a second act.

He enrolled at UNM as nearly a junior thanks to his CNM credits and chose engineering because he didn’t know what he wanted to do and it was the family business. Campbell raced through his undergraduate degree, finishing in 2001 just in time to realize that designing bridges and roads and sewage plants wasn’t his thing.

With May’s advice to keep searching for his niche in grad school, Campbell connected with Prof. Arup Maji, who was doing research on materials for spacecraft components and space structures and was associated with the Air Force Research Laboratory. Campbell found an area of engineering that excited him and he finished his master’s degree in a year, spending most of his time working in the Space Structures Group at the research lab.

“He was always a top student,” says Maji, who funded Campbell’s master’s work and chaired his thesis committee.” When Campbell graduated, May wrote some letters of recommendation.

“This young man is destined for something exceptional,” he wrote. “Whatever he is going to set out to do he will accomplish.”

Campbell, with his wife, nurse Arishanda Campbell (‘00 BSN), left for the mountains of Colorado and worked in design and program development for a company that creates composite materials for harsh environments and another R&D company that had battery technology in its portfolio.

Frustrated with management, Campbell broke out on his own in 2012 and co-founded ROCCOR, a space deployables and small satellite component products company that started as the prototypical two guys in a garage and after some lean years grew to employ dozens and develop technology to remove some of the millions of pieces of debris in space.

Simultaneously, Campbell co-founded Solid Power in 2012, as a spinoff from the University of Colorado Boulder. In just 10 years, Solid Power has designed and is producing a different kind of battery for the electric vehicle market.

Since he stepped down as CEO at ROCCOR in 2018 and sold the company in 2020, Solid Power is his only focus and the company is closing in on mass-market production of its battery cell.

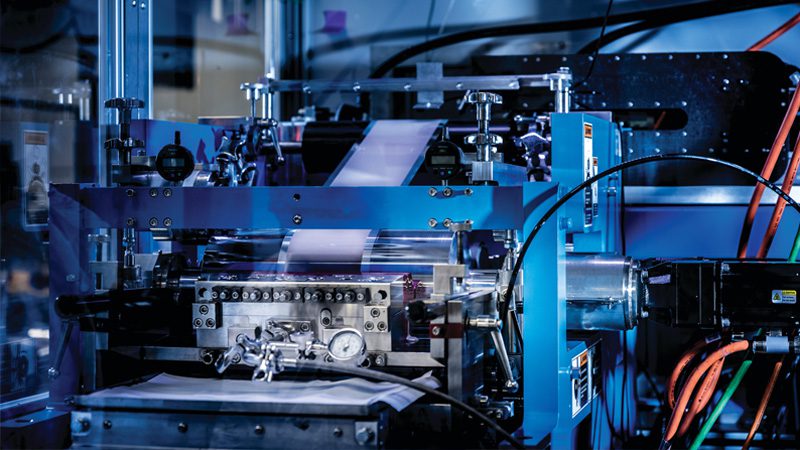

Thin layers of a sulfide-based electrolyte bound for battery cells on the production line at Solid Power.

A Better Cell

Ask Campbell to explain his product and the engineer in him takes pen to paper and draws it out.

Chargeable lithium-ion batteries store energy by drawing ions from the cathode (plus) side to the anode (negative) side through a porous separator encased in a liquid electrolyte. They produce power by reversing that process and releasing electrons. That system has four components: the cathode and anode, electrolyte liquid and a polymer separator.

It is the kind of battery that currently powers the EVs on the road today.

An all-solid-state battery uses the same cathode/anode system but replaces the electrolyte liquid and polymer separator with a single component called an electrolyte separator.

“It is a discreet solid layer,” Campbell says, “so think Oreo cookie: creamy filling and your two little sandwiches.”

By replacing the two components with one solid state package that is more energy-dense, the vehicle’s range can increase by 30 to 50 percent, Campbell says. And because an all-solid-state battery is stable across a wide temperature range, auto manufacturers may be able to eliminate the costly cooling technology they build into electric vehicles.

“At the end of the day this works to deliver higher range and lower cost. That’s why Ford and BMW are working with us,” he says.

The proprietary component that Solid Power is delivering to Ford and BMW is the electrolyte separator.

“Broadly it’s a sulfide-based electrolyte,” Campbell says. Solid Power synthesizes the electrolyte as a powder, then turns it into a slurry (think cake batter), which is pumped into a machine similar to a printing press that pumps out thin layers that are stacked into a cell about the size of an iPad; a process very similar to how today’s lithium-ion batteries are produced.

The company is in pilot production, making hundreds per week.

Solid Power provides only the cells to the automakers, who design the battery packs. Campbell estimates his cells will be in EV models as soon as 2027.

His path from mountain biker to successful entrepreneur with millions to donate to his alma mater can look like a head scratcher. But Campbell sees it all as a perfect arc.

“I have over-the-top ambition. It’s how I’m wired. I’m always go, go, go, go, go. I’m just driven,” Campbell says. “And I’d argue that cycling primed me for business.”

Training all the time, watching your eating, weight and sleep and knowing that not winning a race isn’t failure are fundamentals for an endurance athlete.

“You can’t worry about yesterday’s results, you’ve just got to just train, train, train,” Campbell says. “And that’s the same thing in business. You have to be persistent. You have to ride the highs and the lows. You can’t get too excited in the highs and you can’t get too bummed out in the lows. Otherwise, you’ll drive yourself crazy and you’ll flame out.”

Maji, the engineering professor who funded Campbell’s graduate work, is surprised by the speed and level of Campbell’s success, but not that he’s made it big.

“I’m not surprised in the context of his personality and caliber and zeal to do something different,” Maji says. “He was always a top student. And looking back, I can see why, given the traits that he had, he could certainly blossom into a very successful entrepreneur.”

Giving Back

When Campbell made the gift and specified the department be named for May, Campbell wanted to honor a man who helped change his life.

“I’m greatly honored,” says May, who retired from UNM in 2002 and is 81. “I see a young man who has accomplished extraordinary success at a young age. Quite exceptional. And I think it’s exceptional at this young age that he’s looking to benefit his school.”

Campbell readily admits he is not Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates or Elon Musk. “Five million sounds like a lot, but at the end of the day it’s not,” he says.

So he wanted his gift to be targeted to a small corner of the world that means something to him.

“It’s always been Albuquerque,” Campbell says. “Because even though I don’t live here I’ve always had a passion for this place. Because there’s goodness here. New Mexicans are good people. They’re very down-to-earth people. And UNM is competing with phenomenal research institutions, and I do think it punches above its weight, but it’s located in a relatively small state. I want to make my little corner of the world — the civil engineering department — more competitive.”

Campbell hopes his gift, which will endow a fund to be used at the discretion of the the Civil Engineering Department chair, will help to sweeten the pot to attract and retain world-class faculty.

Part of the plan is to help UNM compete with larger, better-funded universities in the competitive world of startups and spinoffs, a passion close to Campbell’s heart.

“I’m an Albuquerque kid who’s now running a company that the business community pits against spinoffs from Stanford and MIT,” Campbell says. “I’m not intimidated by anybody who comes out of these blue-chip universities.”

Fall 2022 Mirage Magazine Features

In A Solid State

UNM grad helps spark electric vehicle revolution…

Read MoreCourageous Career

Opera singer pivots to performance coaching…

Read MorePretty Good At Math

Alumnus caps computing career with prestigious prize…

Read MoreTelling A Story

Alumna heads up museum devoted to the American Indian experience…

Read MoreFamily Affair

Alumni board president keeps UNM ties tight…

Read MoreAnd the Winner Is…

Alumni take home a Grammy and a Pulitzer for music…

Read More