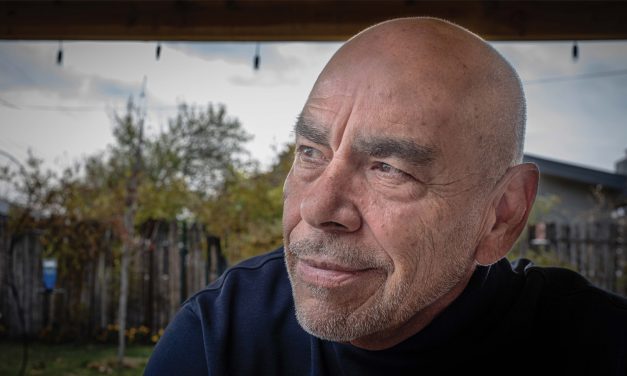

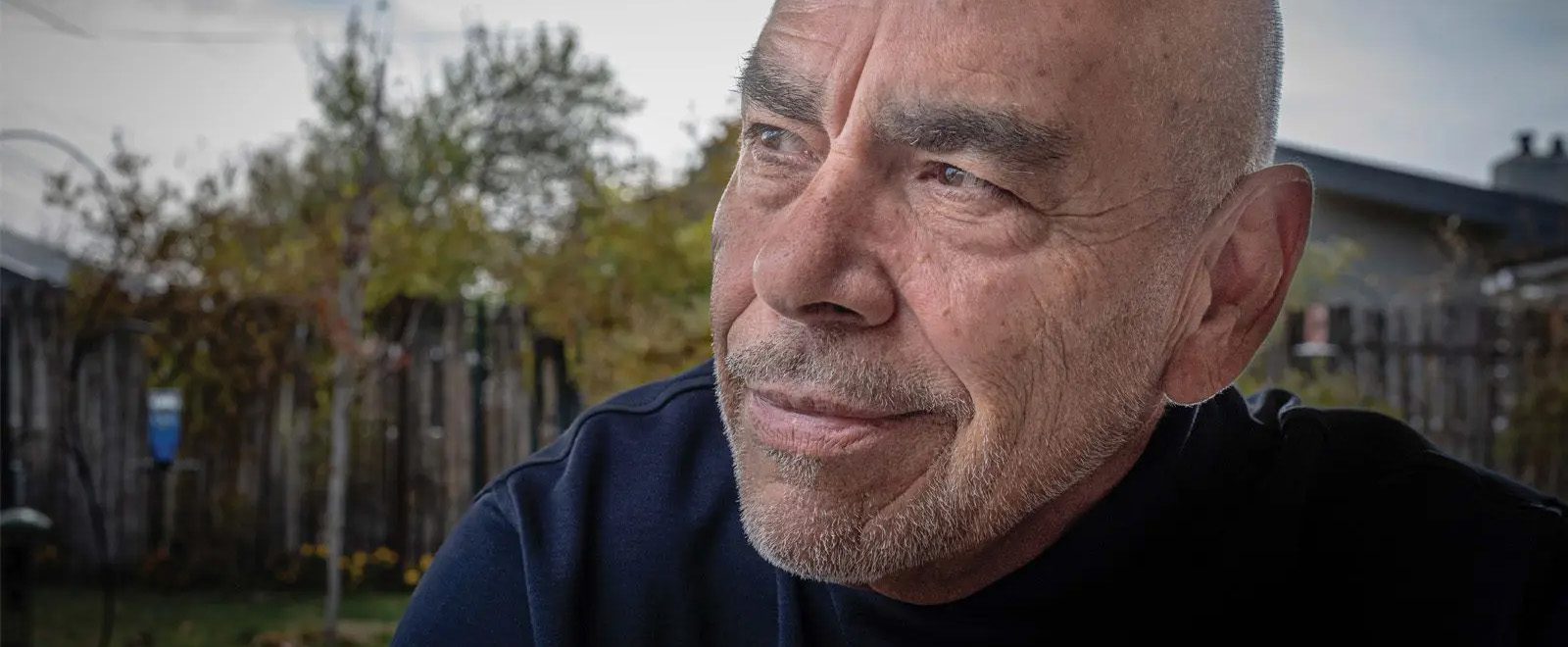

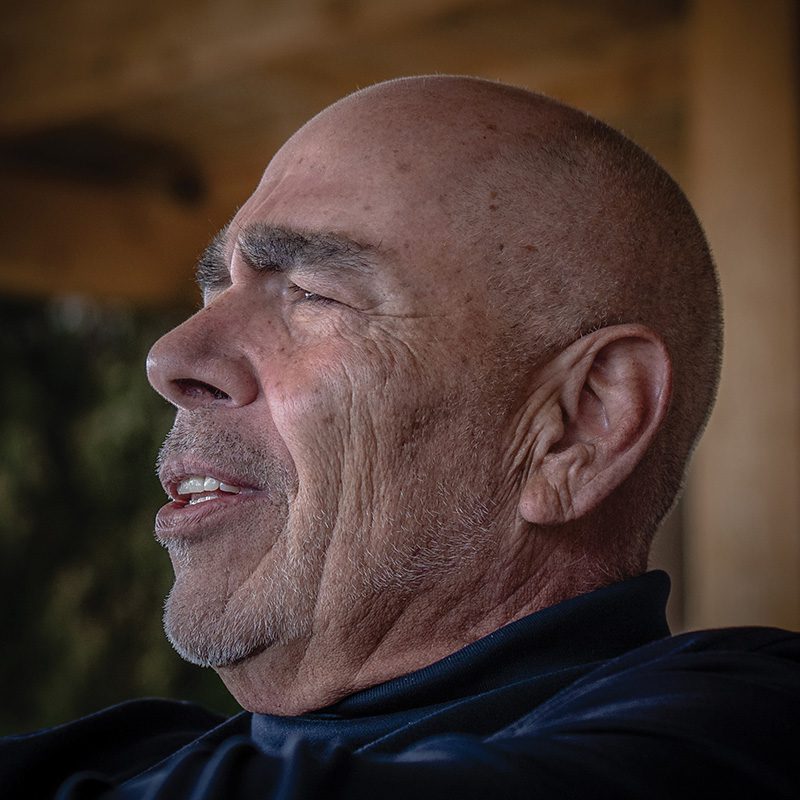

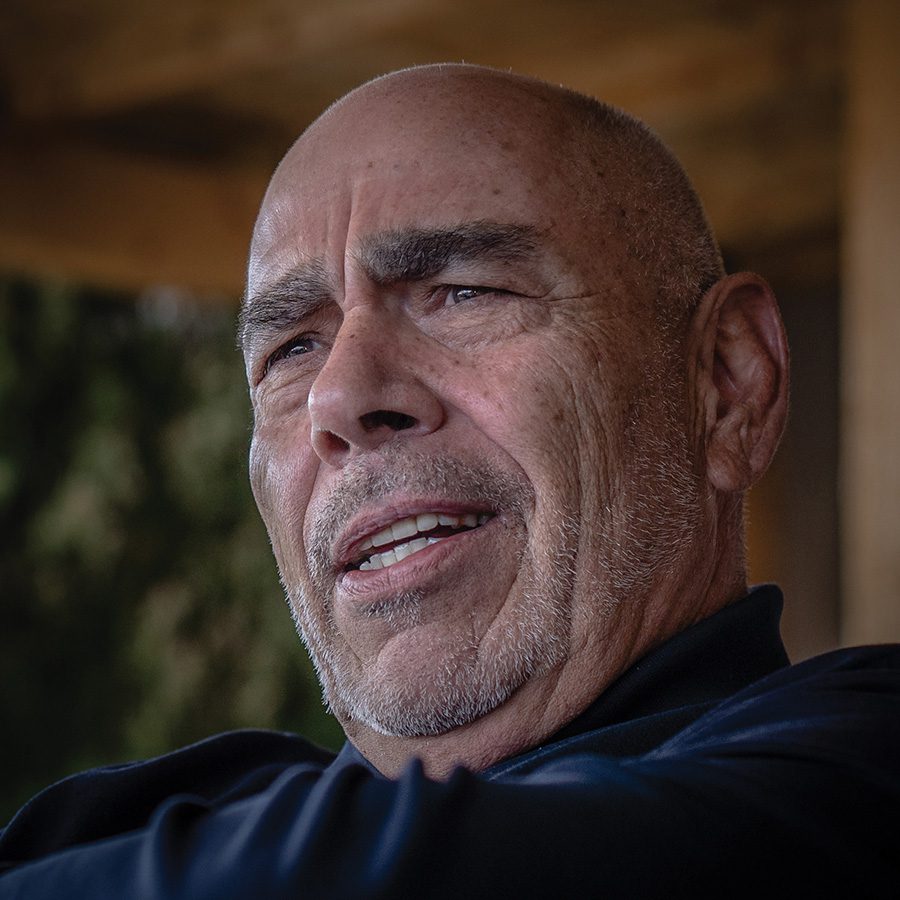

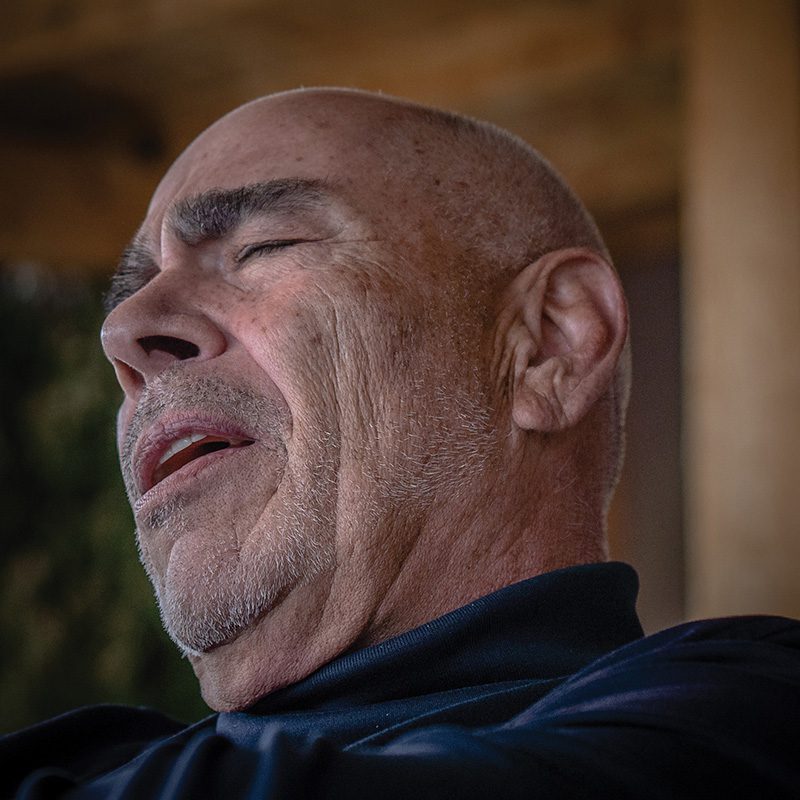

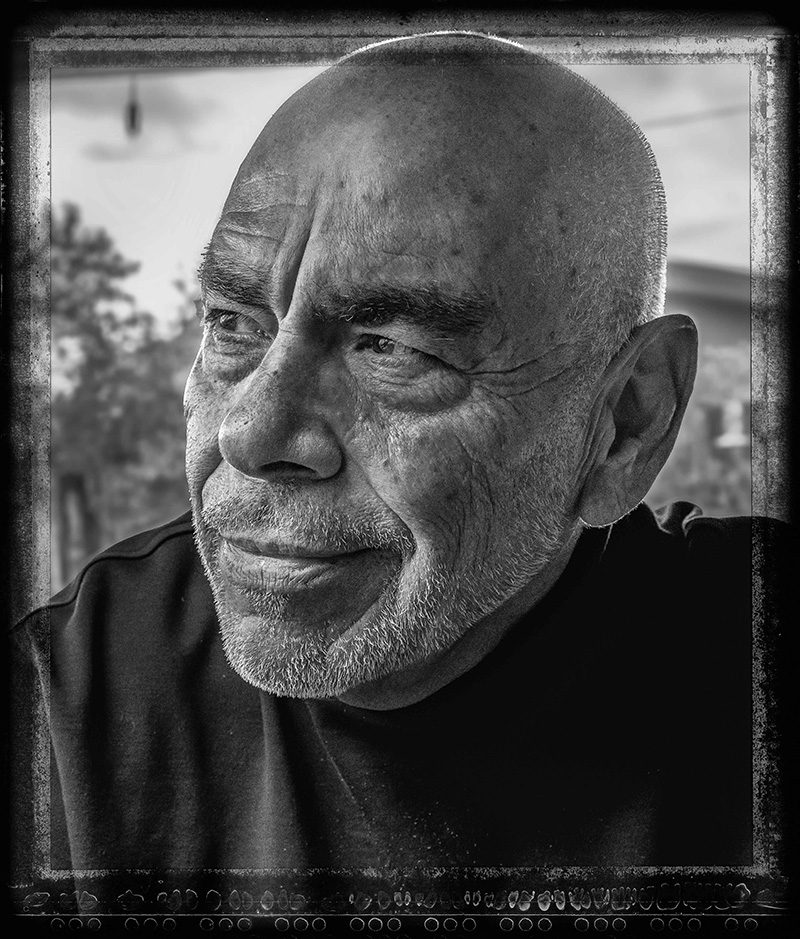

Photos: Roberto E. Rosales (’96 BFA, ’14 MA)

Alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca (’84 BA) found peace in the written word

From Prison to Poet

By Leslie Linthicum

When Jimmy Santiago Baca stands in front of a classroom — maybe it’s a high school in East L.A., or a jail in New Mexico or a seminar at Berkeley or Yale — he’ll challenge aspiring writers to tap into their trauma and find their truth. And he’ll tell them they already have the tools they need: “You have imagination and you have experience,” he’ll say. “That’s where writing comes from.”

And he will likely share his own truth: that books saved his life.

Baca (’84 BA, ’03 HOND), one of the nation’s most prolific and decorated writers, has had 31 books published in 26 languages, and at 70 he still adheres to his morning practice of settling in at the keyboard at 5:30 a.m.

Known primarily as a poet, he also has written novels, short stories and screenplays and is at work on a trilogy while teaching and touring the country reading and lecturing.

It is a charmed life, complete with financial security and a warm family. No one is as surprised and delighted by that as Baca, the former orphan, drinker, drugger and badass criminal.

“A lot of times, no matter how bad things are, I always see myself as being very fortunate,” he says. “There’s not a morning that goes by that I don’t tell the Lord thank you, thank you, thank you.”

His biography has the outlines of a movie and indeed it has been told in a memoir, “A Place to Stand,” published in 2007, and a documentary film in 2014. Born in Santa Fe to a father who drank and was largely absent and a mother who abandoned him and his brother and sister when they were small, he was taken in by his grandparents, then delivered to a Catholic orphanage at age 7, where he lived until he ran away at 13 and was placed in youth detention. At 15, he ran away from there and lived a hand-to-mouth existence, drinking, fighting, getting high, crashing in abandoned homes. Arrested at 17 for a crime he didn’t commit, he spent some time in the county jail before being released. He headed West and was running a lucrative marijuana distribution business in Yuma, Ariz., when he was visiting a heroin dealer’s home as it was raided by federal agents. An agent was shot and Baca was sentenced to five years behind bars for drug possession.

‘I can’t describe how words electrified me.’

He was 20 when he walked into a maximum-security prison in Florence, Ariz., the place where he would teach himself to read and write alone in a cell and begin corresponding with a Good Samaritan who sent him books and paper.

He describes his awakening in “A Place to Stand.”

“I would set my dictionary next to me, prop my paper on my knees, sharpen my pencil with my teeth, and begin my reply. I would try to write the thoughts going through my mind, but they didn’t come out right. They lacked reality. A stream of ideas flowed through me, but they lost their strength as soon as I put them down. I erased so often and so hard I made holes in the paper. After hours of plodding word by word to write a clear sentence, I would read it and it didn’t even come close to what I’d meant to say. After a day of looking up words and writing, I’d be exhausted, as if I had run ten miles. I can’t describe how words electrified me. I could smell and taste and see their images vividly. I found myself waking up at 4 a.m. to reread a word or copy a definition.”

As Baca’s thirst for words grew, he began borrowing books from other inmates.

“Thoreau, Emerson, Dickinson, all the great ones,” he says on a warm morning on the patio of his home in Albuquerque. “Death Row was on the other side of where they kept us, and I was a porter, so I used to be able to go over there and they’d give me their books. They always read the coolest books. Hemingway, Faulkner and a lot of Russian writers. ‘War and Peace’ — come on, that was like my religion.”

Language opened up something in him and what could have been a soul-crushing experience — fights, stabbings, years spent in dark solitary confinement cells because he refused to work — became a rebirth. He fell in love with collections of poems by Shelley, Byron, Neruda and Lorca. He began to review his life through a different lens.

“It was me deciding what I wanted to do with my life,” Baca says. “Me deciding that I probably wouldn’t have made a great criminal but I was really attracted to reading, so I read.”

Sitting alone in the dark for days on end, trying not to go crazy, helped hone writerly skills.

“It was absolutely an opportunity,” Baca says. “You practice your imagination. You practice disembodiment. You practice your memory.”

Baca had plenty of opportunity to practice writing and to dig into the insights and emotions that are the backbone of the poem.

“It was really fortunate to live in a place where death and life met each other every day,” Baca says, “rather than live this passive life where the biggest obstacle is paying the bills and the IRS.”

In exchange for cigarettes or coffee, he wrote poems for other inmates to commemorate events in their lives and to give to their mothers or children or girlfriends. Often, he had to read them aloud to inmates because they couldn’t read.

‘How can you kill and still be a poet?’

When another inmate disrespected Baca and a prison elder advised him he had to fight or be seen as vulnerable as he served out the rest of his time, he came to the realization that his life was changed.

As he recounts in his memoir, he was in the clutch of the fight with the other inmate lying on his back.

“He was partially unconscious, stunned, bleeding from a cracked cheekbone. He took out a shank he’d hidden beneath his sock and I grabbed it. I was standing over him, my feet planted on each side of his shoulders. In that moment, all I could see was his face, the blood pouring out from a wound in his cheek where a bone was exposed. In that moment, everything seemed so calm and quiet. I gripped the shank to stab him. For a second, every horrible thing that had happened to me in my life exploded to the surface as if had been building up to this moment. The blade in my hand, my legs spread over his chest, I loomed over him, staring into his eyes and then at his heart. While the desire to murder him was strong, so were the voices of Neruda and Lorca that passed through my mind, praising life as sacred and challenging me: How can you kill and still be a poet? How can you ever write another poem if you disrespect life in this manner? Do you know you will be forever changed by this act? It will haunt you to your dying breath.”

He chose to become a poet. By the time he was released with $20 and the clothes he entered prison in, Baca had sold some poems to Mother Jones magazine and had contacts with other writers and editors. He went to North Carolina and got his GED and took some community college classes.

Then he returned to New Mexico and had his first collection of poems, “Immigrants in Our Own Land,” published in 1979 and began to make a life as a writer. By the early 1980s, Baca had married, had a baby and bought a fixer-upper. How to pay a mortgage as a poet? Baca enrolled in UNM.

“I needed some money to pay the mortgage and they were offering these Pell grants,” Baca explains. “I had no interest in going to school, but when I got there, I loved it.”

He studied literature, of course, and a new way of looking at books opened up for him.

“I loved the environment of being around so many books. And I really loved the professors,” Baca says. “They had so much to offer. It was like talking to convicts on the yard about writing, but these guys knew all about literature.”

He graduated in 1984 and broke out several years later with the publication of “Martin & Meditations in the South Valley” in 1987, which won the American Book Award and the Pushcart Prize. He won the Taos Poetry Circus — the mother of slam poetry contests — in 1992 and 1993. In 1995 he was invited by PBS journalist Bill Moyers to be part of a televised series on poetry.

Ben Daitz, M.D., a family medicine physician at UNM and a writer himself, met Baca in the poetry slam days and they have remained friends for 40 years.

“His history is pretty dramatic and I think it took him awhile to settle down,” says Daitz, now professor emeritus at the UNM School of Medicine and a documentary filmmaker. “But he did. I think he’s mellowed. He’s more comfortable in his own skin. Part of that is getting older and growing out of his rebellion. And he’s got a great family that is very important to him.”

Baca divorced, married a second time and has four children, one still at home. He has held endowed chairs at Colorado College, Yale and University of California, Berkeley, among other colleges and universities. While he has traveled the world reading, speaking and teaching, he spends more time now in New Mexico, riding his bike, running in the bosque, volunteering as a writing teacher in schools and putting on an annual writer’s retreat. Teaching, as much as writing, has been a foundation of Baca’s life.

“It’s just the service that I think I’m obligated to undertake,” he says. “I was given a great gift. I don’t just want to get rich and famous. I want to spread it around.”

Spring 2022 Mirage Magazine Features

Big League

Rachel Balkovec makes baseball history, former Lobo catcher climbs the MLB ladder…

Read MoreFrom Prison to Poet

University of New Mexico alumnus Jimmy Santiago Baca found peace in the written word…

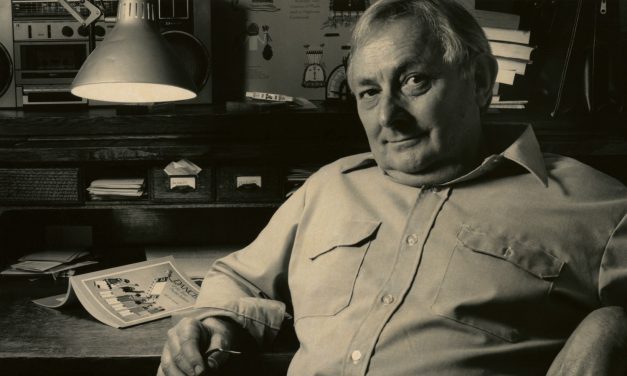

Read MoreProfessor Hillerman

In a new biography, “Tony Hillerman: A Life,” James McGrath Morris devotes a chapter to Hillerman’s years at UNM…

Read MoreForm and Function

Among campuses, which traditionally feature brick, stone and ivy, UNM has always been distinctly of New Mexico…

Read MorePicture Perfect

You can thank an alumnus for creating the image technology that keeps us connected…

Read MoreMy Alumni Story: Joshua Whitman

When I decided to attend UNM I applied to live on campus because I wanted to become involved in student life…

Read More