Making History

Story by Leslie Linthicum Photos by Roberto E. Rosales

Richelle Montoya, who had been a convenience store clerk, executive assistant and the elected president of the Torreon Chapter — one of 110 local government entities on the reservation — was sworn in as the nation’s first female vice president.

When Montoya (’11 BUS) spoke at her inauguration, she said in Navajo, “You are all my children.”

Montoya says that is the principle that guides her as she takes on the biggest and most demanding job of her life.

“I feel that somebody needs to be protective of my family, my children,” she says. “I feel that our men, they haven’t done that. If they did, we wouldn’t have domestic violence.

If they did, we wouldn’t have, unfortunately, incest. We wouldn’t have rape. And so I feel that myself and other women in leadership positions, we have that role now.” Montoya relates her serpentine path to a college degree and myth-busting election at the end of yet another long day as the vice president of the Navajo Nation. Decked out in her customary velveteen blouse, concho belt, turquoise necklace and Apple iWatch. She has been up since 5 a.m. participating in the Northern Navajo Nation Fair, waving to the crowds from the Navajo Nation float in the legendary Saturday morning parade, and then driving from Shiprock to Albuquerque to get a little sleep before a 4 a.m. wakeup call to represent the tribe at the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta.

Life has changed dramatically for Montoya since she first applied to join the Nygren campaign and then listened to the election results on election night. She moved from her home into the official residence of the vice president in the Navajo

Nation capital of Window Rock, Ariz.

She organizes her days around travel to communities around the vast reservation, which spreads into the states of Arizona, Utah and

New Mexico, and meetings in Window Rock with constituents, often fueled by a white chocolate mocha from Starbucks.

Recently separated from her husband of 11 years, a split she attributes in part to the pace of her new job, Montoya lives with her adult son Trenedad, who she can rely on to keep the house running.

“At this point, don’t even ask me how much a gallon of milk is,” Montoya says. ” I’m not going to the store.”

Montoya was born and raised in Torreon, the easternmost community on the reservation. By the time she was nearly 30 she had bounced between her home, nearby Cuba and Albuquerque working at a series of jobs at convenience stores. She was working as a clerk at the 7/11 in Cuba and taking care of her three young children when her older sister suggested she apply to the Albuquerque Public Schools temp pool.

She got hired and wound up answering the phones for the Indian Education Program. Her boss, Nancy Martine Alonzo from the Ramah Navajo community, eventually hired her fulltime, then promoted her to executive assistant and then data technician.

Alonzo, who was working toward a master’s degree in education administration at UNM, then gave Montoya the bad news. Without

a college degree, she could never move up further in the school district. She encouraged Montoya to go to college.

“She talked to anybody and everybody who worked for her about education and how important it was,” says Montoya.

Montoya took the advice seriously, but when her mother suffered a heart attack, she moved back to Torreon to help her recover.

It took her sister’s prodding and example — Vivian Montoya-Watuema enrolled at UNM and earned her BA in 2009 — to persuade Montoya she could have a place in higher education. Starting at CNM in Albuquerque, Montoya studied police science, then transferred to San Juan College in Farmington, where she received her associate’s degree.

When she walked by a UNM recruiting table at San Juan, she realized she could pursue a bachelor’s degree at UNM without leaving Farmington, where she had settled with her husband Olsen Chee and their blended family of six children.

Montoya enrolled and took all but one of her classes at a UNM satellite in Farmington.

By the time she walked with her graduating class at the Pit and received her diploma in University Studies, Montoya had no grand plans for a career, “I just wanted my degree, that was it,” she says. “I wanted that piece of paper, that diploma that said, Richelle Montoya finished something.”

With her husband no longer able to work, Montoya took a job as executive assistant at DNA-People’s Legal Services in Window Rock, and she spent a lot of her time chaperoning her daughter Autumn during her 2018-2019 reign as Miss Navajo.

Montoya also began to consider public service. Her father had served as chapter secretary and vice president in the Torreon chapter and had encouraged his children to be involved.

Montoya joined the local school board and then, frustrated that issues such as domestic violence and language preservation weren’t being adequately addressed, she ran for and won the election for chapter president.

“I became president of my chapter because no one was listening to me,” Montoya says.

She met the future Navajo President Nygren when he spoke to her chapter via Zoom during the pandemic and then called her up after the meeting to ask how he did. She eventually joined his campaign and was then asked to apply to be his running mate.

She liked Nygren’s story — like her, he was the child of divorce who lived without electricity and running water and spoke Diné fluently. And, like her, he was committed to bringing services in the sprawling nation up to date and solving problems by consensus. She was also impressed that he was committed to picking a woman to serve beside him.

“One of the things that I’ve always done in my family is we don’t have gender roles,” Montoya says. “I always brag that my daughters can go outside and chop wood and do oil changes and my sons can make food, do the laundry, clean the house.”

In her new job, Montoya believes she brings an approach to decision- making rooted in a long line of matriarchs who went before her.

“I feel that I bring the perspective of, ‘Slow down, let’s look at this issue from every single aspect that we can — yours, mine, hers, his, theirs. And let’s see what solutions everybody has. Let’s see which one has worked, which one hasn’t worked and let’s not repeat what’s not working.’

And a lot of the time, it’s just me listening.”

During the campaign, Montoya talked openly about her history with domestic violence. Her mother, who was married at 14, suffered abuse at the hands of her father, which led to their divorce. Her grandmother was also abused and her daughter had experience with a controlling boyfriend.

“I have three biological children,” Montoya says. “Each one of them has a different dad, and each one of the relationships ended because of domestic violence. And I kept saying, ‘No more. I’m not going to do this.’”

Although domestic violence was not part of the administration’s platform, women come to Montoya to seek help and she listens and tries to iron out red tape that’s getting in the way of their obtaining protective orders.

“I feel like my mom’s mom went through it. My mom went through it. I went through it. My daughter got through it a little bit. And now I’m like, hopefully my granddaughter never has to.”

At the Balloon Fiesta in Albuquerque, Montoya got a balloon ride and time to be alone with her thoughts. She visits the annual fiesta to connect with the spirit of her late son, Romeo, who was born in Albuquerque on Oct. 5 and was held by his mom as she watched balloons float by.

While her family is central to Montoya’s life, she has drawn a wall between them and her official duties.

“One of my biggest asks of my family is not to be around,” she says. “That’s my way of protecting them.

I don’t want them to be around my office or events. I want them to be home. I want them to live their lives. I want them to continue to do their traditions, their prayers, and everything they possibly can do to include me in on those because, of course, I need it.”

Spring 2024 Mirage Magazine Features

Understanding Headwaters

Understanding HeadwatersJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 A $2.5 million grant from...

Read MoreNo Je or No Sé?

No Je or No Sé?Jan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 In his research, Associate Professor...

Read More‘A New Pair of Eyeglasses’

‘A New Pair of Eyeglasses’Jan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 Nancy López,...

Read MoreSenate Judiciary and Mental Health

Senate Judiciary and Mental HealthJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 Colin Sleeper, a...

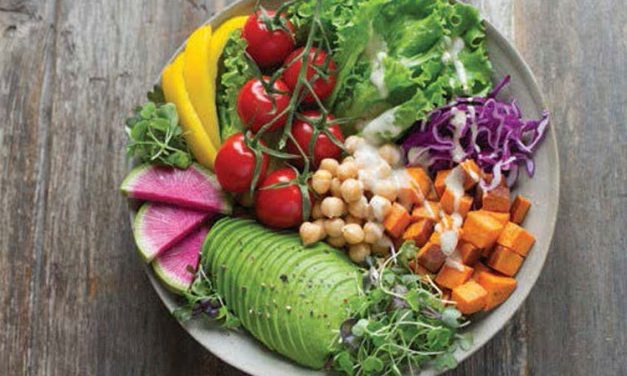

Read MorePlant Power

Plant PowerJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 More people are choosing plant-based...

Read More