In a Place Where We Can Celebrate

Diné filmaker Shaandiin Tome turns her lens to native people…

Read More

Diné filmmaker Shaandiin Tome (’15 BFA) turns her lens to Native people

By Ellen Marks

It all started with a 7-year-old girl and a VHS camcorder tucked away in a back closet.

The girl was Shaandiin Tome, and the camcorder had been a Mother’s Day gift that her brother dragged out one day from its out-of-the way spot.

The siblings and their cousins put it to good use making movies, and Tome began narrating her young life in a manner similar to today’s social media influencers.

“I would say, ‘Hi, my name is Shaandiin,’ like I had a pretend audience,” she says.

More than two decades later, the audience is no longer pretend.

Tome is now an acclaimed filmmaker who is also winning success as an indigenous cinematographer and director. She graduated from The University of New Mexico in 2015 with a bachelor of fine arts degree in film and digital media production.

Last year, Tome was honored with the James F. Zimmerman award, which the UNM Alumni Association gives to graduates for outstanding achievement.

Her latest project, “Long Line of Ladies,” drew top jury prizes for best short documentary at the South by Southwest festival in Austin and at the San Francisco and Seattle international film festivals. That made the project eligible for a 2023 Academy Award for best documentary short film, although it did not go on to make the cut through advanced competition rounds.

Tome’s 22-minute film, which she co-directed, tells the coming-of-age story of a 13-year-old member of Northern California’s Karuk tribe. Ahtyirahm “Ahty” Allen is preparing for her “Ihuk,” or Flower Dance, a tradition the tribe has worked to revive since the 1990s.

The practice was abandoned after the California Gold Rush brought sexual violence to Native American girls and women — a history that Tome’s film relates, but doesn’t dwell on.

Shaandiin Tome

“I think it’s one of the first indigenous, Native documentaries that celebrates a young woman and celebrates a family.”

Tome, who is Diné, wanted her story-telling to be a joyous celebration.

“I think it’s one of the first indigenous, Native documentaries that celebrates a young woman and celebrates a family,” says Tome, 29. “And it doesn’t focus on the traumas of native people. It gets it out of the way in the beginning, with title cards that talk about the Gold Rush forcing ceremonies to lie dormant, but it doesn’t focus on that.”

It’s part of Tome’s struggle: to tell a story from the perspective of a young Native woman that includes history, which is often violent, but also resilience and pride.

“I want there to be something that’s positive and uplifting, that serves as a reminder that we are a people that have adapted and gone through circumstances for a reason, and now we’re in a place where we can celebrate,” she says. “We don’t have to be at the whim of people who are trying to place their traumas on us.”

Adam Piron, director of the Indigenous Program at the Sundance Institute, says Tome is among a generation of young Native filmmakers who are “embracing their identity more.”

Piron worked with Tome starting in 2016, when she was chosen for the Sundance Full Circle Fellowship, which focuses on indigenous young adults. The next year, she was named a fellow at the institute’s Native Filmmaker Lab.

“She’s a Diné woman who grew up in more of an urban environment,” Piron says. “There’s always sort of an urban versus rural tension in our community. Her journey to embracing who she was and where she was coming from, you see that a lot in her work.”

Tome was born in Albuquerque and attended Cibola High School, although she also has lived in Denver, Fairfax, Va., and the Navajo Nation. Her father, Deswood Tome, is a former Navajo Nation spokesman, and she says both parents are artists.

Tome’s summers growing up included stays at her grandmother’s house, on the reservation in Arizona near the New Mexico border.

Tome says Albuquerque and the Navajo Nation have always been her home, as well as the “through line of my life.”

Her breakout short film, “Mud,” mirrored her personal experience with the issue of wintertime exposure deaths in the Gallup area, mostly “among people leaving bars,” she says.

It focused on the last day in the life of a woman told “through the lens of addiction” with the goal of “trying to give a humanistic portrait of a stereotype that’s been pinned on us,” Tome says.

The film, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018, was based on one of Tome’s relatives, whose belongings were found in a ditch but whose body wasn’t found until weeks later.

“My dad was very affected by it,” she says. “He was the one who identified the belongings.”

She notes that while a lot of her work is “Indigenous-based,” she also has done a variety of other projects. For example, her growing resume includes work for brand companies such as Vox, Levi’s and Brooks, and for media organizations such as PBS and National Geographic.

“She can write, she can shoot, she can edit, she can produce, and she has mastered all of those at a really high level,” says Miguel Gandert, former director of the UNM Interdisciplinary Film & Digital Media Program. “One thing about her is she’s fearless.”

But that wasn’t always true.

Tome says she got “really depressed” during the three years she spent working on film industry sets while attending UNM and just after graduating.

“There’s something very magical about films that I felt from a young age,” Tome says. “But I started seeing that creativity was not part of the equation. It was competitive and wasn’t a space for a marginalized woman, for marginalized people in general. It was really tough to figure out, ‘Is this really what I want to do with my life?’”

Her breakthrough came when she joined the prestigious Sundance, where she learned that “independent film is thriving, and that stories from anybody and everybody are viable.” She says she started writing her own material and “working with peers I loved and adored. It was a complete life-changer for me.”

The film she’s now working on is a series of vignettes “about the life of a car, told through people who have owned it.”

Her grandfather was a mechanic, and the family had to rely mostly on cars that were given to them or borrowed as needed. So, she says, a car in her family was really much more than just a vehicle for getting around.

“You have an attachment to an object, and you feel that it can be taken away at any moment,” she says. “It’s kind of a metaphor for how society quickly gets rid of things and tosses them aside, versus caring for something.”

Her future also includes trying to have more balance, both in her life and in her approach to story-telling.

“I think it’s hard to be in a place to express yourself while also trying to express a whole people, and you end up fighting with yourself a lot,” Tome says. “In my teachings, you want to lead a very balanced life. You are really trying to carry your ancestry with you, but then also trying to carry the future with you. It’s very much a balance of trying to figure that out. But you have to rely on it, too. It’s like you’re not on this journey alone.”

Diné filmaker Shaandiin Tome turns her lens to native people…

Read MoreUNM Alum expands on her father’s literary legacy…

Read MoreUNM’s second-largest college is poised to move onto Central Avenue…

Read MoreTriple alumna followed her dream from Vietnam to a doctor of nursing…

Read MoreNASA’s newly employed James Webb Space Telescope is reaching ever deeper…

Read MoreWhen I was in high school, my family relocated to Rio Rancho…

Read More

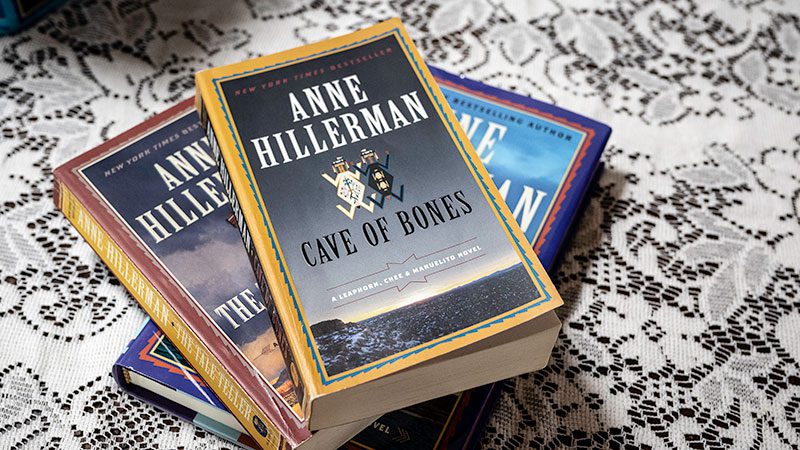

UNM AlumNA Anne Hillerman ( ’72 BA) extends her father’s literary legacy

By Leslie Linthicum

Winding down his writing career, author Tony Hillerman talked a time or two with his eldest daughter, Anne, about the next book he had in mind for his series of detective stories featuring Navajo police Lt. Joe Leaphorn and Sgt. Jim Chee. It would have mercury poisoning as a subplot and, with his energy flagging due to age and illness, he raised the possibility of her doing some research for him.

But “The Shape Shifter,” published in 2006, would be his last novel. Hillerman died in 2008 of Lou Gehrig’s disease and with him his popular Chee-Leaphorn series which had run for 36 years and included 18 titles, leaving legions of fans to mourn.

Anne Hillerman, a journalist like her father, had several nonfiction books to her credit, but it hadn’t occurred to her that she might carry on the Hillerman franchise.

“He and I never talked about it. He never said, ‘Why don’t you and I do some books together.’ And I never brought it up,” she says. “I thought that, you know, was his territory.”

In the last years of his life, father and daughter and her husband, photographer Don Strel, collaborated on a project to photograph the landscapes of the Southwest and Indian Country that played such a major role in his mystery stories. To find passages to accompany the photos, she reread each of her father’s novels, then she and her husband traveled through New Mexico and Arizona.

As she toured the Southwest promoting “Tony Hillerman’s Landscape: On the Road with Chee and Leaphorn,” which was published the year after her father died, she talked to legions of her father’s fans and began to realize the hole his death had left.

“I had thought, ‘You know, nobody lives forever and that was the end of it,’” Hillerman says. “But then when he wasn’t around to do it, I thought, well, it’s just a shame for the stories to end.”

We’re talking around the kitchen table in the home she lives in outside of Santa Fe. Coffee is brewing, a storm is threatening and the Ortiz Mountains look like they’re going to get some snow.

The nearly 15 years since her father died have brought more loss. Hillerman’s mother, Marie, died in 2015 at age 87. Two of her brothers died in 2017 and 2022. Hillerman’s husband died in 2020 of acute myeloma and dementia.

Anne Hillerman

“I figured all I could do was the best I could do.”

But Hillerman, who has a wide smile and a ready laugh, has kept Chee and Leaphorn alive. As she talked to her father’s fans and felt herself missing the fictitious world he had created, she began to inch toward the idea of continuing the series.

“With great trepidation,” she says. “I had never written a novel. And I think when most people write a first novel, your family reads it, maybe a few friends. I had the possibility of embarrassing myself in front of a lot of people.”

But Hillerman had written a lot of words in her career. Having seen her father happy in his career with the United Press International and The Santa Fe New Mexican, Hillerman graduated from UNM with a major in journalism. (At the time her father, also a UNM alum, was a professor and chair of the Journalism Department and she took two of his classes.) She also briefly worked for UPI and wore many hats at The New Mexican and the Albuquerque Journal.

So she started to map out a story and sat down to write.

“I figured all I could do was the best I could do,” she says.

Hillerman didn’t want to channel her father; she wanted her books to be her own. She brought Chee and Leaphorn back, but put Leaphorn in the hospital gravely wounded in the first chapter and developed one of her father’s minor characters, Chee’s wife, Police Officer Bernadette Manuelito, into the star of the book.

When she was finished writing “Spider Woman’s Daughter,” Hillerman printed out the book and gave it to her mother over the Thanksgiving holiday. Marie Hillerman was Tony’s first reader and a careful editor.

“My mom was very wise and a very good editor, and also very gentle,” Hillerman says. “So if there was anything she said that was less than supportive, I would know that the book just stank.”

Her mother called her the day after Thanksgiving and said, “Well, I read your book.”

“What did you think of it?”

“I think your dad would be proud.”

Hillerman puts her hand on her heart and tears form at the memory.

“It doesn’t matter how old you are, those are magic words,” she says.

Her mother had some notes, which Hillerman took on board and then she sent the manuscript to her dad’s former editor at HarperCollins.

“Yeah, who knew?” she says laughing. “I think some of the fans, some of the diehard fans, were curious enough that when they saw the name Hillerman they thought they’d take a chance.”

Since “Spider Woman’s Daughter,” Leaphorn has continued his recovery from a brain injury while Manuelito has continued to take center stage and develop as a full character. In Hillerman’s second book, “Rock with Wings,” Manuelito struggles with work-life balance – juggling an investigation following a puzzling traffic stop with taking care of her aging mother and troubled younger sister.

It’s obvious that Hillerman is a different author from her father, bringing the concerns and sensibilities of her gender to the series.

Hillerman, 73, said she broached the idea of writing Manuelito as a more skilled officer in 2006, when his “Skeleton Man” was published.

“I said to Dad, ‘I think readers would enjoy seeing Bernie take the next step and be on the same level as Jim Chee and Joe Leaphorn.’ I thought he’d say, ‘Oh, honey, what a good idea.’ No, what he said was, ‘What an interesting idea.’

“But in the end, I was glad he didn’t do it,” she says. “Because that gave me a chance to continue the series, but to give it a different voice and my own perspective – a female perspective – by giving Bernie not only a job but also giving her what every working woman has, which is a lot of complications.”

“Rock with Wings” also found a place on the New York Times bestseller list and so did each of her following novels – “Song of the Lion” (2017), “Cave of Bones” (2018), “The Tale Teller” (2019), “Stargazer” (2021) and “The Sacred Bridge” (2022). “The Way of the Bear” is due out in April 2023

By now, Hillerman is a bona fide franchise, but she doesn’t wear her success. She lives in a beautiful but modest adobe house with her partner, Dave Tedlock (’73 BA), and accepts just about every speaking engagement she is offered – traveling to the smallest New Mexico rural libraries to engage with her fans.

Jean Schaumberg, Hillerman’s longtime friend and business partner in a series of writers’ workshops, including the annual Tony Hillerman Writers Conference, has watched as Hillerman made the transition from working journalist to first-time novelist to big-time author.

“Her star has really risen,” Schaumberg says. “But she’s just like her dad. Her dad was a humble man and she is down to earth. She doesn’t put on airs. I think her dad would be really pleased – or is pleased in heaven – that she has taken his characters and done so well with them.”

With each novel, Hillerman begins with a setting and a topic – anything from medical marijuana to paleontology to Navajo astronomy.

“After I choose the setting, which really is like a character in my stories, then I think, what crime would be appropriate in this setting?”

Once she has the crime and the setting, Hillerman skips the common practice of outlining her plot and chapters.

“Usually I write a letter to myself, and I say, what is the point of this book? Why are you going to spend a year doing this? What do you want to accomplish?” she says. “And usually in that letter, I deal with what happened in the last book that I was not exactly satisfied with, that I could do better in this book. And then I just kind of start writing.”

She writes in the morning, seven days a week, in a cozy room with views on all sides. After she’s finished at the keyboard for the morning, there’s lunch, dogs to walk and things to attend to on the business side of being a novelist.

But her book is never far from her mind.

“Even if I’m not consciously thinking about it, I realize some part of my brain is working on it,” she says.

Once her first draft is roughed out, Hillerman goes back and begins writing the book her readers will eventually hold in their hands.

“Once I’m done with the first draft, then the flow really hits because then I can see the shape. Then I can work on refining the language and the nuance of the characters and their situations and all that stuff.”

“Some days, it is really a struggle,” she says. “Like I’m kind of falling asleep. It’s really hard to stay focused. And some days I’ll be sitting there and the next thing I know, two hours have gone by and I realize I had to go to the dentist at 10 and now it’s five till.”

Hillerman fell into the mystery genre because that is what her father did. She finds comfort in its restrictions.

“You have the box, the mystery genre, and you know what has to go into the box and the readers do too,” she says. “I find it kind of a relief to have everything wrapped up at the end of the book. Maybe some of your subplot strains move forward, but basically the crime is solved, your detectives are still alive, justice is served.”

But a good mystery novel doesn’t just kill off bad guys and wrap up the loose ends by the last page. Hillerman, like her father, brings poetry to the page.

Bernie Manuelito returns to the trailer home she shares with Jim Chee: “She could hear the rhythmic chuckling of the San Juan River and a symphony of crickets through the open windows.”

Jim Chee on an interrupted personal retreat at Lake Powell: “Over the past few days, Chee had hiked for miles, slept beneath a million shimmering stars, seen hawks, coyotes, rabbits, deer, ravens, several kinds of lizards, and enough rattlesnakes to fill a cowboy hat.”

Hillerman plans to write two more Chee/Leaphorn/Manuelito books.

“After that, I don’t know,” she says. “There might be something else I would like to do before going back to them.”

Hillerman is also is an executive producer of the AMC television series “Dark Winds,” now in its second season and filming at Camel Rock Studios on Tesuque Pueblo. The series, created with fellow executive producers Robert Redford and George R.R. Martin, is based on the Hillerman characters and she approved their use.

“I was nervous about how they would be portrayed,” she says. “It’s kind of like sending your child off to high school. I was hoping for the best, but you never know.”

She has been delighted with the series and with how the cast has taken to the material.

“After the premiere, all of the main people in the cast came up to me and they said they were really honored to have those roles because they were such positive roles for Native people, and that they were, you know, really grateful to me and to my dad.”

Hillerman has been thinking about a couple of her minor characters that might want to carry their own book.

“So, I don’t know,” she says. I think it’s always good to reinvent yourself.”

Triple alumna followed her dream from Vietnam to a doctor of nursing practice degree

It was the early 2000s, and she was 32, newly divorced with full custody of four children – ages 4 to 12 – and she had been working full-time at a jewelry company.

But a job in the medical field was her lifelong dream. She had held that dream close, even while fleeing her native Vietnam in the aftermath of the Vietnam War on a perilous boat journey and then making her way as an immigrant in the United States.

“It was not only my childhood dream, but I had to work hard to get my children out of the situation we were in and do better in our lives,” says Bui-Burgos, who is now a hospice nurse and an Albuquerque restaurant owner. “I always felt like I didn’t get on that boat and risk my life to not pursue my dream.”

The boat was a wooden one that Bui-Burgos’ mother placed her into so she could leave Vietnam for a Malaysian refugee camp, with the eventual destination of her father’s home in California.

Tina Bui-Burgos

“because it’s not always going to be easy. It can be really rugged, but somehow, I managed to do it.”

On the journey she was a 10-year-old “orphan,” Bui-Burgos says, with only neighbors but no family accompanying her. It was a trip of horrors that included being robbed by pirates three times.

“Two girls just a little bit older than me were kidnapped and probably thrown overboard, because they were never heard from again,” she says.

Those experiences underlie Bui-Burgos’ determination to make a new life and to take on increasingly difficult professional challenges.

Bui-Burgos, now 52, does nothing halfway.

She is a three-time alumna of The University of New Mexico College of Nursing, receiving her bachelor’s degree in 2007, her master’s in 2011 and her doctor of nursing practice in 2021.

Her education spanned nearly two decades, including a few gaps, and her resume includes stints in UNM Hospital’s Neuroscience ICU, pediatrics, internal medicine, gynecology and a variety of other family practice settings.

One of her favorite work experiences was at Santo Domingo Pueblo, where she spent three years in the clinic as a way to give back to her adopted state.

“I just felt like there were not enough providers going into rural areas to take care of Indigenous people,” she says. “I wanted to bridge that gap.”

She also has created the Bui-Burgos Endowed Scholarship in Nursing through the UNM Foundation, in the same spirit of honoring those who have helped her through the years. The scholarship is aimed at single parents seeking a nursing career, she says.

Meanwhile, she recently was named to a committee serving the New Mexico State Board of Nursing.

Bui-Burgos’ current hospice work for a private home health care company is part time, because she also loves the restaurant business and has owned Relish, a sandwich shop near Uptown, for the past 10 years.

Her drive and dedication sometimes baffle her now-grown kids.

“My kids constantly say, ‘Mom, I don’t even know how you did it because I’m only taking care of myself, and I can’t even figure out how to go from my work to the gym, and my house is a mess.’”

She tells them that success starts with knowing what you really want before settling on your dreams and goals. “At 10 years old, I knew that I was going to seek a better life,” she says.

The second part, she says, is to stay organized and persevere, “because it’s not always going to be easy. It can be really rugged, but somehow, I managed to do it.”

Alumnus looks deeply into space

By Glen Rosales

NASA’s newly employed James Webb Space Telescope is reaching ever deeper into the great depths of the universe and its infrared eyes seem to deliver fresh insight into the cosmos every few weeks.

Its ability to peer deep into space from its location nearly 1 million miles from Earth not surprisingly had astronomers eagerly lining up for time on the new observatory.

Michael DiSanti, PhD, who earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees from The University of New Mexico in 1978 and 1980 respectively, has been among those who have had a chance to work on a project using the Webb Telescope.

“It’s been a long time coming and everybody was submitting proposals,” said DiSanti, who is a staff scientist in the Solar System Exploration Division at the NASA-Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “I was in on three different proposals.”

Only one of the three was selected, a proposal spearheaded by colleague Adam McKay, PhD, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Appalachian State University in Boone, NC.

Webb designers have given it a five-year mission window with a hopeful ultimate goal of 10 or more years of use, meaning astronomers have a limited time frame to cram in as many projects as possible. “So each proposal was weighed on its potential value to advance science that cannot be done from Earth’s surface,” DiSanti said.

“Ground-based (telescope) time is very competitive, but not like Webb,” DiSanti said. “There is a lot of money involved, and resources.”

DiSanti’s Webb project is to study Centaurs, which he describes as a “dynamical class of small bodies orbiting the Sun between the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune.”

The Centaurs “are transitioning from orbits in the scattered disk of small solar system bodies beyond Neptune to those of short-period comets — also referred to as ‘Jupiter-Family Comets’ — that enter the terrestrial planet region closer to the Sun where their activity is dominated by release of water, the most abundant ice in most comets,” he said.

“Gas release has been observed from some Centaurs using ground-based and space-based telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope. However, measuring chemicals that vaporize at the cold temperatures beyond Jupiter’s orbit — namely carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide — with ground-based facilities has proved challenging (for CO) or impossible (for CO2). And the presence of water has been found in just a single Centaur,” DiSanti said.

The study uses Webb’s Near Infrared Spectrograph to obtain observations of H2O, CO2, and CO in a targeted suite of active Centaurs, and includes sensitive searches for water ice absorption in the coma,” DiSanti said.

The telescope is uniquely suited for this study because it “can measure the strongest bands of H2O and CO2, neither of which can be observed from the ground because they are totally obscured by Earth’s atmosphere, and also CO, all with unprecedented sensitivity. Obtaining an inventory of H2O, CO2, and CO in active Centaurs is vital to understanding their composition and activity,” he said.

DiSanti grew up in the small village of San Cristobal north of Taos, adopted along with his brother by acclaimed folk singer and New Mexico folk music ethnologist Jenny Vincent and her husband Craig, after their father died.

DiSanti grew up in the small village of San Cristobal north of Taos, adopted along with his brother by acclaimed folk singer and New Mexico folk music ethnologist Jenny Vincent and her husband Craig, after their father died.

He left the wide-open starry skies of northern New Mexico to study astrophysics and chemistry at UNM and stayed for a master’s in physics.

DiSanti went to the University of Arizona for his PhD. His thesis looked at ionized water vapor in comet Halley.

Since then, his focus has remained on comets, those streaking lumps of ice, rock and dust that contain the record of the conditions of the early solar system.

That’s why closer study of Centaurs is his focus now — because of the clues they provide as to how solar systems are formed.

“What we can learn from comets, including Centaurs, can teach us about chemical conditions in regions that cannot be observed directly,” he said. “There’s a cottage industry of chemical modeling of disks around stars. And yet we can’t really see directly into the cold disk midplane region, as there’s a lot of material blocking the wavelengths of interest. So that’s another important aspect of comets. They provide a means of probing the once heavily shielded midplane region of our solar system’s own protoplanetary disk.”

Centaurs, much like Pluto, spend billions of years in the Kuiper Belt, a flattened distribution of solar system bodies beyond Neptune, before they get kicked into closer trajectories.

“It’s mostly primitive material remaining from the formation epoch,” DiSanti said. “Centaurs are part of the puzzle. Exactly how they fit, we don’t yet know, but the Webb study is expected to provide key insights.”

“Four of the six targeted Centaurs have already been observed through Webb, and analysis is ongoing,” DiSanti said. Publication of initial results is expected sometime in 2023.

As I was graduating high school, I was fortunate to receive a UNM Presidential Scholarship, and I enrolled at UNM to stay near my family. Once classes started, I began to appreciate how lucky I was to be at UNM. I’ll never forget discovering the Zimmerman West Wing reading rooms and feeling that maybe my idea of “home” was shifting. I dove head-first into campus life: during my sophomore year, a few friends and I co-founded a new student organization. As a junior, I enrolled in UNM’s study abroad program and lived in the UK. And in my senior year, I joined the National English Honor Society and met the three people who would become my lifelong friends.

UNM empowered me to try new ideas, make mistakes and grow. I became involved in political activism and discovered a passion for sexual and reproductive health and rights. After graduating in 2006 from UNM’s English Language & Literature program, I studied public policy at the University of Chicago and worked at several non-profit health care organizations. I’m now the national director of Data Strategy, Analytics, and Governance at Planned Parenthood Federation of America ¬– my dream job.

When I think about “home” now, I feel a sweet mix of memories: the endless green fields and late summer thunderstorms of Illinois – and also sunsets on the Sandias and the scent of piñon in crisp winter air. UNM taught me that home is where you are seen and loved; it is what we carry in our hearts, no matter where life takes us.

Erin Barringer-Sterner (’06 BA)

Recent Comments