Diversity Matters

Story by Leslie Linthicum Photos by Roberto E. Rosales

They wanted their sons, like other children, to see themselves represented in the books that would help shape their young minds.

So Laurel, who graduated from UNM in 1985 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology and earned a master’s in counseling and family studies in 1989, made books of her own. She carefully glued photos of her sons and some of herself and her husband over the pictures in the books.

The books, charming and one of a kind, allowed Kalen and Forrest to see themselves, in their moccasins and ribbon shirts, as heroes of children’s literature. But the exercise was born of a necessity Laurel found disturbing. The boys are grown today, with careers in the arts and journalism, and the state of representation of Native Americans remains dismal.

Just under 2 percent of children’s books are centered around a Native American character and a little more than 1 percent of children’s book authors are Native American. “My generation turned a blind eye to the system,” says Goodluck, now part of that 1 percent of Native American authors of children’s books, with her sixth and seventh titles sold. “It’s like we didn’t see ourselves for decades and decades. And we just accepted it.”

But the payoffs for Native American children when they see themselves, their foods, their families and languages represented in books they find in their school or a library are immense, Goodluck says.

“Oh, gosh,” she says. “They feel valued. They feel seen. They feel treasured. All the things that all kids feel when they see themselves in books as a hero of a story solving problems and critically thinking. As their identities are forming, books can be a source that makes them feel proud and stand tall.”

After graduating from UNM, Goodluck worked at several nonprofits, including Futures for Children and the New Mexico Family Network. She took some time off to raise her sons and then spent a decade managing her husband’s medical practice.

When her oldest son was graduating from college in New York City, Goodluck visited and they went to two museum exhibits that changed the course of her career. One, at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, featured the work of three generations of Inuit women who created prints and drawings of village life, rich with celebration and joy, but also with a critical eye toward modernity and its effects on Inuit culture. “Part of their theme was to tell people we’re still here in this modern world,” Goodluck says. “I was really struck by that because I’d been so caught up in my work in medical administration that I kind of forgot that, yeah, we do still need to tell people that our people are still here and living in this modern world.”

Then, they went to the Studio Museum in Harlem and saw an exhibit of picture books written and illustrated by members of the black community depicting their modern lives in their own voices and lived experiences. The art and stories were vibrant and beautiful, and she was in awe. “I had never seen picture books or children’s books like that before, books that were written by black authors and illustrators representing their own communities. And by the time I got home, I was like, maybe I can do this,” she says. “So that’s when it began.”

Book publishing traditionally is a white industry famously closed to diverse writers and illustrators. And Goodluck had never written a book.

She began to research what makes a successful kid’s book, how to build characters and tell stories. Her online research led her to the nonprofit organization We Need Diverse Books, which advocates for diversity in publishing in terms of authors and subject matter, and everything clicked. “I thought, ‘They’re playing my music,’” Goodluck recalls.

The organization has conferences and mentorship programs for published and aspiring authors.

Goodluck missed a deadline for the mentorship program, which gave her another year to practice and grow. The following year, 2019, she was accepted and paired with Traci Sorell, a Cherokee author who lives in Oklahoma.

Sorell, the former director of the National Indian Council on Aging in Albuquerque, met Goodluck when she came back to Albuquerque for the launch of her own children’s book. When Goodluck applied to become a mentor the next year, Sorell liked Goodluck’s subject matter and drive. “I knew if she was willing to do the work, she could definitely get where she wanted to go,” Sorell says. “And she absolutely was.”

Sorell worked with Goodluck on the unique craft of writing a children’s book, which usually runs no more than 500 words and uses illustrations to tell large parts of the story. And, as importantly, she taught her how to navigate the system of conferences and grants for Native writers. Sorell also sent her out to the library to study recently published picture books and then asked her to drill down to what kinds of stories she wanted to tell.

“She really focused, concentrated, made time, which was not easy given that, you know, she’s balancing having her day job managing her husband’s medical practice and trying to nurture this creative career,” Sorell says. “And by the end of our year together she had an agent and was selling manuscripts.”

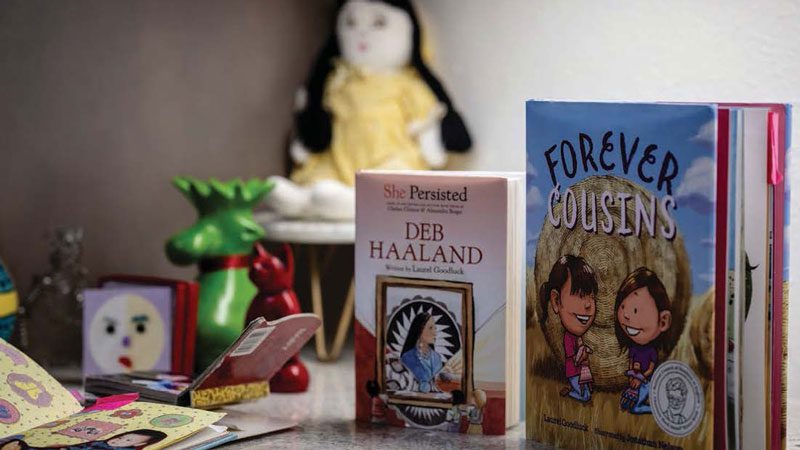

Meanwhile, Goodluck also expanded and found her community of Native writers. At one conference, Goodluck connected with a cadre of Native writers who stayed in touch on Facebook after the conference ended and developed a critique and support group that helped her give birth to her first book “Forever Cousins,” which she sold to Charlesbridge publishers in 2020.

It tells the story of two cousins who fear their bond will be ruined when one moves with her family back to the reservation. It’s a universal theme of love, family and friendship, sprinkled with Indigenous culture. At the back of the book, the author’s note is where Goodluck likes to explain the inspiration for the story and the erased Indigenous history not told in the United States educational system. In “Forever Cousins,” she writes about the Indian Relocation Act that brought her parents and other Native people to the cities in an unjust assimilation program.

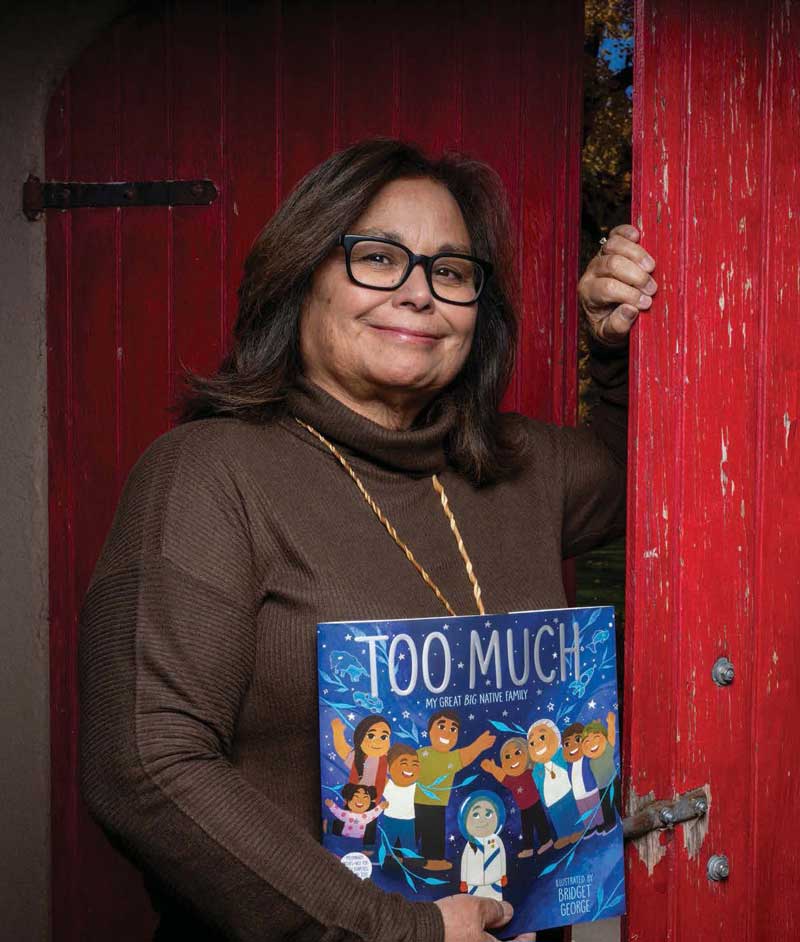

Laurel Goodluck with one of her many children’s books.

“They feel valued. They see feel seen. They feel treasured. All the things that all kids feel when they see themselves in books as a hero of a story solving problems and critically thinking. As their identities are forming, books can be a source that makes them feel proud and stand tall.”

While others baked sourdough and banana bread during the COVID-19 pandemic, Goodluck was impressively productive. She wrote and sold three books to three major publishers.

“Forever Cousins” was published in 2022; “Rock Your Mocs” was published by HarperCollins’ Heartdrum imprint in 2023; “She Persisted: Deb Haaland,” a chapter book for young readers, was published by the Penguin Random House Philomel Books imprint in 2023.

Kevin (BS ’86, MD ’94) who met his future wife at the Kiva Club at UNM, closed his medical practice during the pandemic, which allowed Goodluck to concentrate on writing.

Her latest books are “Too Much: My Great Big Native Family,” published by Simon & Schuster, due out in 2024. “Fierce Aunties,” published by Simon & Schuster’s Simon Kids imprint, and “Yáadilá! (Good Grief!),” published by Heartdrum, both due out in 2025. “Stories Are the Heart of the World,” which Goodluck calls “a love letter to my sons,” is due out in 2026.

It’s quite a feat for a novice writer who never pursued an MFA. She started to learn to write when she was 56, had her first book published when she was 60 and, at 61, is now a mentor to other writers.

Goodluck looks to her upbringing to help explain her success.

“I grew up hearing oral storytelling,” Goodluck says. “And that tradition of learning about my people’s struggles and legacy through these stories really did help me as I began to learn this industry and ask what I can do to give that to kids in a new way, a new form, so that they can rely on their culture that they can be resilient and strong.”

For young Native readers, Goodluck’s goal is simple: “That they can see their culture like a superpower that they can rely on and be their whole selves.”

For non-Native readers, she aims to dispel stereotypes, for example Native people portrayed in children’s literature as caricatures wearing feathers and warpaint, by depicting Native people living in the real modern world. “I guess I hope that they get that their world is bigger than what they know that they open up their world the same way my world was opened up when I would go traveling as a kid and see other people in different cultures and the way they lived,” Goodluck says. “I think when they’re young, they have their mind wide open. And then they kind of lose that; it gets closed up. So that’s another reason for writing for young people is having an impact on them on a young age.”

Goodluck continues to write and is now a mentor herself to a new crop of Native writers.

“I am just ecstatic to see not just the things that she has put out in the world, but all the things that are to come,” Sorell says. “She is absolutely one of the most beautiful, giving, creative souls, so having her sharing stories with young people is wonderful and with her mentoring she is now bringing more people from underrepresented communities and marginalized voices into the industry, which is exactly what we need.“

Spring 2024 Mirage Magazine Features

Understanding Headwaters

Understanding HeadwatersJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 A $2.5 million grant from...

Read MoreNo Je or No Sé?

No Je or No Sé?Jan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 In his research, Associate Professor...

Read More‘A New Pair of Eyeglasses’

‘A New Pair of Eyeglasses’Jan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 Nancy López,...

Read MoreSenate Judiciary and Mental Health

Senate Judiciary and Mental HealthJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 Colin Sleeper, a...

Read MorePlant Power

Plant PowerJan 7, 2025 | Campus Connections, Spring 2024 More people are choosing plant-based...

Read More