How UNM adapted to the oddest of academic years

By Leslie Linthicum

Professor Eva Chi and her team of instructors in the Department of Chemical & Biological Engineering spent their summer puzzling through some big academic challenges: How to teach a hands-on, upper-level chemical engineering lab course under social distancing restrictions.

Owen Whooley, as associate professor of Sociology, had his own concerns. Should he teach his Health, Medicine and Human Values course entirely online or try for an anything-but-normal in-person class once a week? How could he encourage class participation in a disembodied virtual world? And how could he connect with students he would never see in person?

As the Spring 2020 semester ended in a hurried rush out the door and academics finished online, students were left to wonder what the Fall semester would look like and faculty members in every department scrambled to improve their online chops.

The strangest academic year anyone could imagine at UNM has played out over the past few months mostly on computer screens. For some it has meant freedom never enjoyed in a normal school year — freedom to travel, work and complete coursework from anywhere at any time. For others, it has been a series of hurdles — to focus and to find human connection.

Freshman Year Reimagined

It feels like we’re stuck in a cycle that we can’t get out of.

– Jaanai Giselle Martinez

“I imagined that I would be able to go to the library with my friends. I would gather for lunch,” Martinez says as her first semester winds down. “I imagined I would take advantage of any opportunity we got to socialize to the point where I would almost never be alone.”

Instead, Martinez has been closed in a four-bedroom apartment-style dorm suite with three roommates for the entire semester taking all of her courses online.

“Luckily, I got a good group of roommates, so because of them I feel like I have a little bit of a social circle,” Martinez says. “We do everything together, which is a good thing and bad thing sometimes. We don’t really see anyone else, just to play it safe.”

Inside the apartment, the four don’t wear masks, but they mask up any time they leave their unit.

All are members of the close cohort of freshman in the Combined BA/MD Degree Program, which puts them on a path to UNM’s School of Medicine after they successfully complete their bachelor’s degrees. Martinez, who has wanted to be a doctor ever since she can remember, is taking general pre-med courses — chemistry and calculus — along with Spanish and a sociology course that focuses on medicine.

Since arriving on campus in August, Martinez has never walked into a classroom building and attended a course with other students. She hasn’t met any of her professors. Even the experiments in her chemistry class have been online.

Martinez “attends” scheduled classes each day, but they are all remote.

Some of Martinez’s roommates are in the same classes, so for those they put the course on the TV in their living room and watch and take notes together.

“We try to make it feel as normal as possible,” she says.

Martinez, who is 19, took some college courses at Central New Mexico College during high school and she misses the interaction with instructors that happens during class and also less formally in the minutes before and after class.

“I know what it feels like to just able to go to your professor and ask them something or just even ask them how their day is. And because of the mode we’re in, it’s hard to even ask how is your day, because you’re interrupting a class. There’s no asking for help. There’s no making conversation,” she says.

The social life of a freshman, which can be exciting and sometimes distracting, isn’t happening. For fun, Martinez and her roommates stream movies or TV shows in their apartment.

“One time me and my roommates walked through campus,” Martinez says, “but we got very lost and had to use GPS to get back.”

Even La Posada, the dining hall, looks different. Instead of getting a meal and then finding a table to sit and eat with friends, all meals are packaged to go and meals are eaten outside or back at the dorm.

Even so, Martinez is happy to be on campus, to prevent the distractions of home. And she is grateful for the relationships she has developed with her roommates.

Learning New Moves

I decided I wasn’t going to pretend this was normal.

– Owen Whooley

“It’s not anyone’s fault, obviously, but I do feel like we were robbed a little bit. Robbed of what we could have potentially got from our education,” Martinez says. “It feels like we’re stuck in a cycle that we can’t get out of that just involves our room.”

One of the bright spots in Martinez’s schedule has been her Health, Medicine and Human Values course, which examines how social factors shape health outcomes. Part of the course work is keeping a “COVID diary,” where students relate the concepts they learn in class to what is going on in real time with COVID-19.

Martinez can see the meaning behind the concepts playing out in the news every day, and she looks forward to the course because of the professor’s enthusiasm.

“He doesn’t seem like he’s lecturing; he seems like he’s just talking to us,” Martinez says. “He’s a professor I would have loved to meet in person.”

Owen Whooley, an assistant professor who was on the other side of the Zoom screen for Martinez’s sociology course, is relieved when told he was able to break through the glass barrier created by remote teaching.

“This was all uncharted territory,” says Whooley, who has been teaching for eight years at UNM and has taught Health, Medicine and Human Values seven times.

Normally he would meet his students in Dane Smith Hall or another classroom building. Students — 28 this semester — would be arranged in desks and he would lecture, use PowerPoint, lead discussions and assign small group projects to be done in class.

“It’s a lecture-discussion hybrid and one of the things that’s changed this year is it’s more lecture than I would like,” Whooley says. “Rather than drone on and on, I like to keep them on their toes and encourage active participation.”

Whooley was on sabbatical when campus closed at the end of the 2019-2020 academic year, so he missed the difficult transition from in-person to remote teaching. Over the summer he took advantage of a week-long online teaching training provided by UNM and he thought a lot about how to engage students virtually.

He hoped to make the course an in-person/remote hybrid, but he would have been able to meet with only one third of his students once a week to allow sufficient distancing. “I quickly realized that was going to be untenable,” Whooley says. “I’ll be honest — I didn’t want to teach online. I’ve never taught online before and I’d never wanted to teach online, so I tried hard to maintain some sort of in-class element. Fear of the unknown was a major motivator, but you really lose something when you’re not in the same space. You lose the informal interactions that happen before class and after class. You lose the feedback. You lose some of the intimacy and you lose some of the community.”

But like so many things during the pandemic, he made peace with the situation and worked to make the best of it.

Whooley ended up restructuring most of the class, scrapping a group presentation and replacing it with a group paper, and establishing a discussion board that resembled a text chain in an attempt to preserve group interaction.

For class, Whooley set up his camera in his home office with a burnt orange accent wall behind him and on occasion his two small children piping up from their home classrooms in other rooms of the house. And the class was conducted twice a week much like any business meeting or extended family gathering conducted on Zoom, with him and his students appearing on a grid.

“I learned quickly how to hide myself, because I don’t like lecturing to myself,” Whooley says. Zoom is simultaneously more distant and more intimate because faces are so close.

“At first I was pretty insistent on having students keep their cameras on, but I quickly realized it was kind of sensory overload to have 25 faces staring at you,” he says.

To encourage participation, Whooley lectured for several minutes, then paused for questions or discussion, then resumed lecturing.

“I would say it went better than expected but not as good as it normally does,” he says. “You develop a certain style that works for you, a certain classroom performance. And I don’t think I fully adapted that online. I tend to be far more funny and have a banter back and forth. I felt like my jokes fell flat.”

Opportunity From Chaos

It’s complicated.

– Sharon Chischilly

In preparation, Whooley reflected on the question: What does it mean to learn during a global pandemic?

“People are stressed out. They’re isolated. They’re alienated from their family. These are freshman who are starting a huge transition under really crappy circumstances,” he says.

He decided not to pretend the class was normal and concentrate on making sure his students were OK.

“So, more so than I normally do, I tried to convey to the students, ‘Look, I know this is hard. We’ll get through this. If you need anything, come to me. I care about you.’”

In mid December The New York Times published its annual The Year in Pictures, featuring the best photos published in the year. Representing the month of November was a bright photo of a posse of Navajo Nation tribal members heading to vote on horseback on election day. The photographer was Sharon Chischilly, a junior journalism and communications major at UNM.

Disruption caused by the pandemic has had odd benefits for Chischilly. When UNM decided to finish the Spring 2020 semester online, Chischilly went home to Manuelito, N.M., on the Navajo reservation. The Navajo Nation was being ravaged by COVID-19 and Chischilly took advantage of free time to photograph its effects.

She met a reporter from The Washington Post at a food distribution event who asked her if she might sell some photos to the newspaper. That led to her first freelance assignment and broke open a new world for Chischilly.

Chischilly, who describes herself as a self-taught photographer who still has a lot to learn, now has the kinds of photo clips many veteran photojournalists only dream of.

“Strangely, for me, I was given an opportunity to work for The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal while going to school online,” says Chischilly. “There’s a lot of negatives about what’s happened — it’s hard to see my people struggling. And this has tested me emotionally and mentally. But there’s a lot of positives.”

Chischilly was taking four classes last Spring semester while juggling her new freelance career, and she tried to be at home or at a McDonald’s with free WiFi during her scheduled Zoom classes. One afternoon, with class meeting scheduled, she found herself on a reservation road far from internet.

“I pulled over on the side of the road and got on using my phone. But there’s not really good service here and it kept dropping me out,” she says. “I was freaking out.” When she reached reliable internet she messaged the instructor, who understood.

When the Spring semester ended, Chischilly took the summer off and got an internship at the Navajo Times in Window Rock., Ariz. She continued to freelance through the summer. Caught up in freelancing, working and helping her family in Manuelito (her father lost his job during the pandemic), Chischilly missed the deadline to apply to renew her tribal scholarship. Because she had to pay for school on her own, she chose to go part-time for the Fall semester and juggled only two courses — journalism and photojournalism — while continuing to work. She maintained her spot in the dormitory at Lobo Rainforest and bounced back and forth between Albuquerque and the reservation so she could attend her photojournalism course, a hybrid in-person/online model.

With a limit on six students and everyone in face masks or face shields, “It was really strange,” she says. But it allowed for something approaching a normal course.

As the Fall semester neared finals, Chischilly was offered a full-time job at the Navajo Times.

Pre-pandemic, she would have had to choose between a job in her chosen profession or finishing her degree. With the pandemic continuing unabated and UNM’s Spring 2021 semester online, Chischilly could have both.

“It’s complicated,” she says. “If this pandemic wasn’t happening, I wouldn’t be where I am today.”

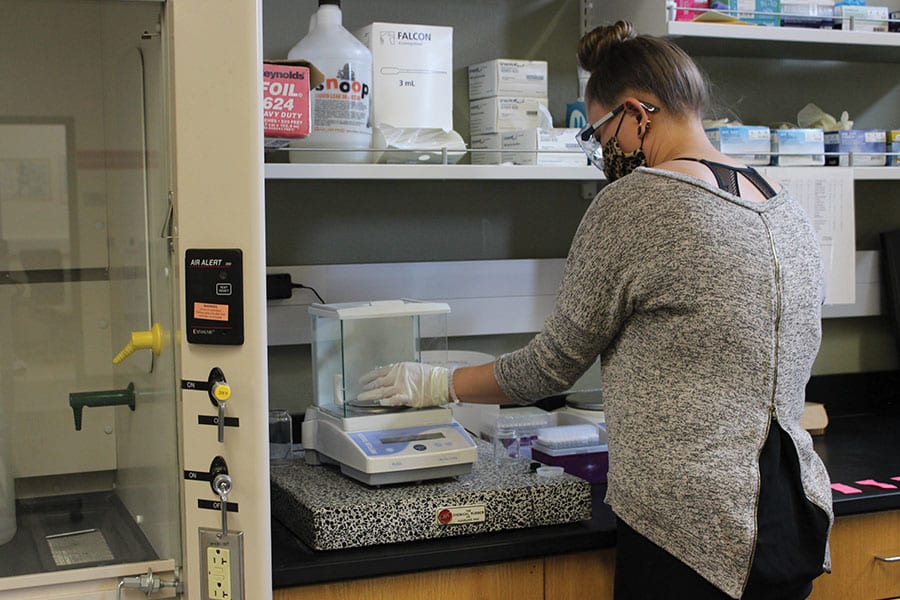

Eva Chi, a professor and Regents’ Lecturer in the Department of Chemical & Biological Engineering, had the summer to consider how to reimagine a chemical engineering laboratory course for seniors. Labs are normally bustling places that rely on human connections to puzzle through problems.

“We started to talk in earnest about how we have to do things differently in that class because the way we had done it before was just not going to work — with the restrictions from the University and also just for the safety and well-being of our students and us,” Chi says.

The mission was how to minimize contact and exposure to COVID-19 but also provide a good learning experience. Chi had never taught online, but members of her instructional team had experience with online learning.

“We changed everything,” she says.

Rather than choose a textbook experiment for the course’s main objective of teaching chemical distillation, Chi took a page from breweries and distilleries, who were using their knowledge of distillation to rush much-needed hand sanitizer into the community.

When the class convened online, the syllabus was all about safety and creativity — learning about the chemical distillation process, talking to local brewers about their techniques and then designing a lab experiment that would ideally result in hand sanitizer that could be distributed to a community of need identified by each student team.

“I suppose we could have done it the way we did before, but we thought, ‘This is a great opportunity for us to make a change,’” she says. “It was the spirit of what can we do for our community and how can we make this relevant. It was the spirit of — hey, we are problem solvers.”

Chi felt the coursework tapped into the goals of chemical engineering majors — to improve the environment and health of communities.

Rather than have each of the 70 students perform two experiments during the semester, the lab component was pared to just one experiment. Some international students had returned to their home countries over the summer and not returned. Other students had health conditions that made interaction in a lab unsafe. So Chi divided the class into four-person teams and had the teams choose only two members to come to the lab to perform the experiment.

Experimenting with Science

We changed everything.

– Eva Chi

Students watched a series of videos to understand the lab process rather than watching an experiment in person before they designed and conducted their experiment. Chi visited the lab twice and saw students in person, but the rest of the course was completely virtual and asynchronistic, meaning the students could access the lessons whenever they wanted within a week.

“It’s been a really hard transition for lots of reasons,” Chi says. “How do you build a community when you don’t see each other?”

Chi required more video reports than written reports, she said, so students had to show up in front of their camera and speak to someone. Instead of messaging her feedback, she also recorded videos so students could see and hear her.

Toward the end of the semester, Chi also reimagined the curriculum to focus on the daunting tasks ahead for seniors graduating during the economic and social disruption of a pandemic — applying to grad school or finding a job. She reached out to alumni and friends and invited them to present video seminars about their jobs or graduate programs.

Chi intends to take some of those new practices forward, even it is safe to return to in-person class.

“I don’t think we’ll go back to how it was,” she says.

Colman Sandler, one of Chi’s students, visited Broken Trail Spirits and Brew, a craft distillery and brewery in Albuquerque that early on in the pandemic distilled ethanol to formulate hand sanitizer, which it offered for free.

He learned about the chemistry of their distilling process and he and his teammates decided to start with a solution based on vodka — 40 percent alcohol — to get to the end product of a hand sanitizer that was 80 percent to 85 percent. Team member Alycia Galindo worked out the calculations that would tell the distillation column what to do during the experiment.

Galindo, who was taking six classes during the semester, also found an extra push to perform because the class project was relevant.

Locked Down Senior Year

It was actually really motivating.

– Alycia Galindo

Locked away in a room of her family home in Albuquerque to study without distractions during the online semester, Galindo was excited to work on something relevant and useful and also to have the opportunity to design her own distillation process rather than rely on an experiment from a book.

“It was actually really motivating,” says Galindo, 21. “We were actually doing something that could help the community during the pandemic and it was really exciting to go into the lab

and actually see what we designed from scratch come to life.”

The lab day was challenging, as Sandler and Galindo had only a few hours to familiarize themselves with the complicated distillation column — a tall glass cylinder that separates water and alcohol according to predetermined calculations to arrive at a desired solution.

Holing up with his roommates and attending his classes online, Sandler found the lab one was one of the bright spots in a dreary semester.

“I was definitely more motivated for the lab than I was for my other classes,” Sandler says.

Sandler also appreciated the professional development portion of the course, as he struggles with whether to choose graduate school or industry when he graduates — most likely via Zoom — later this year.

Galindo, motivated by what looks like a bleak job market, is applying to PhD programs for next year. And she found her six-course semester in lockdown was a success.

“It was a lot to handle, but personally I kind of enjoyed it,” Galindo says. “I couldn’t go out with friends, so all I could do was school work. When people ask someday, ‘What did you during the pandemic?’ I’ll say I sat there and I learned!”