UNM graduates develop biomedical devices with an eye to earlier diagnosis of diabetes complications

By Leslie Linthicum

Jeremy Benson (’16 MS)

Aswathy Kurup (‘17 MS)

Jeff Wigdahl (’13 MS)

Diabetes affects one in 10 Americans, in many cases causing vision loss or a painful complication known as peripheral neuropathy that leads to foot ulcers and, in its most advanced form, amputations.

In a suite of offices near the Albuquerque International Sunport, Simon Barriga (’02 MS, ’06 PhD) and a team of scientists and engineers at a biotech company called VisionQuest Biomedical are inventing early detection devices and software to catch complications of diabetes early and improve the lives of millions of people living with the disease.

“We want to do it cheaper, we want to do it faster and we want to increase diagnosis so everyone can have preventive tests,” says Barriga, a co-founder of the company and its CEO. Their ally in the work, he says, is artificial intelligence.

“There are multiple diseases you can diagnose using artificial intelligence,” Barriga says. Taking data collected over time on patients’ eyes, in the case of retinal disease, or feet, in the case of peripheral neuropathy, and training a computer network to recognize patterns of disease and health allows for computer-aided diagnosis.

Artificial intelligence-driven software that has seen millions of disease patterns can help doctors make a better diagnosis, or can make a diagnosis on its own, freeing doctors to focus on early treatments.

“One of the main things that we focus on is to detect diseases early, where they can be caught and treated before there is severe consequence,” Barriga says. “We want to prevent complications that end up costing a lot of money to the health system and to the patient if they are prevented from providing for their families.”

The eye

The company’s main product is called EyeStar. Diabetic retinopathy is the most common complication of diabetes. It occurs when the blood vessels inside the eyes retina begin to fail, causing hemorrhaging and inflammation. Unchecked, it causes vision loss.

Many diabetics don’t know they have the condition until it is too late. Although the condition can be detected in an annual eye exam and treated, fewer than half of diabetics get an annual eye exam.

“There are very good treatments for that now,” Barriga says, “but the key is to detect it early.”

VisionQuest’s rapid eye-screening technology uses a camera that takes a picture of the retina, without requiring dilation of the pupils. The picture is uploaded to the cloud, where VisionQuest’s artificial intelligence-driven software analyzes the image and within 30 seconds delivers a diagnosis.

The technology has not received approval for use in the United States from the Food and Drug Administration, but it is being used in a network of diabetes clinics in the city of Monterrey, Mexico. The technology has been used in exams on 35,000 people in Mexico and its early detection is credited with saving 5,000 of those people from going blind, Barriga says.

“Our plan is to put this in pharmacies, so if you’re going to get your medications in the time that you wait to get your prescription, you can get your pictures taken and get your eyes examined and get your results right away without having to have an appointment with an ophthalmologist.”

The foot

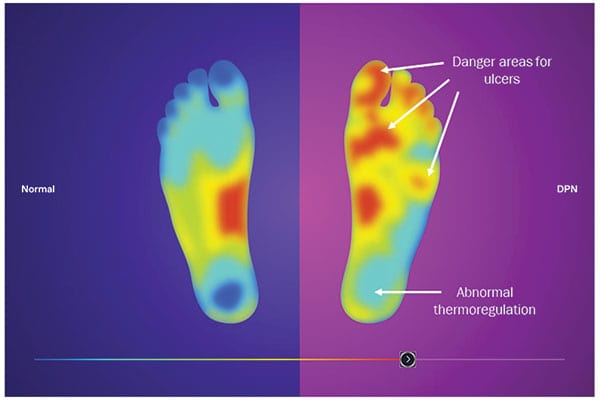

In peripheral neuropathy — known more commonly as “diabetes foot” — blood vessels in the hands and feet break down, damaging the nerve endings and causing the loss of feeling. Minor cuts or other damage go undetected and lead to infection and sometimes amputations.

VisionQuest’s device and technology, awarded a U.S. patent in 2014, uses infrared cameras and artificial intelligence that can detect the effects of diabetes in limbs early on.

VisionQuest is working with UNM’s School of Medicine to perform a clinical study, paid for by a $3 million, three-year grant from the National Institutes of Health, that will test VisionQuest’s device on several hundred patients with diabetes. Researchers hope to begin enrolling patients this spring.

David Schade, MD, an endocrinologist at UNM Health Sciences Center and professor of internal medicine, will be working with Peter Soliz, PhD, the principal investigator in the grant, on performing the study.

Currently, physicians rely on tapping or tickling a diabetic patient’s foot to assess nerve responsiveness and send patients for further imaging if they suspect damage.

VisionQuest’s system works by detecting temperature changes in the feet. After applying a cold patch to the foot, the technology measures how quickly blood flow returns, lighting up compromised areas of a foot, which differ from the pattern of a healthy foot. In an instant, a clinician can pinpoint where compromised nerve endings are failing to deliver blood and begin to work toward better control of the disease and better limb care.

“Right now, there are not very good tools to determine any of this,” Barriga says. “The tests out there are very subjective. This will give a very good quantitative test.”

Surprising career

Barriga grew up in Trujillo, Peru.

“I was always good at math,” he says. He dreamed of being a physicist, but his practical mother encouraged him in the direction of engineering. “So, I chose the engineering that was the closest to physics,” Barriga says, “and that was electrical engineering.” In an irony, many of his high school classmates wondered if he would end up in medical school, which he discounted because of his distaste for biology at the time. “So, to my surprise,” Barriga says, “I’ve been working for 20 years in medicine.”

Barriga received his undergraduate degree in Peru, and at age 26 he came to UNM for graduate school in the College of Engineering and stayed for his PhD. His thesis analyzed data from a device invented at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, N.Y. that used light to stimulate the retina and look for changes. It was his first work in ophthalmology and led to his joining VisionQuest shortly after it was founded by Soliz, one of his advisers at UNM.

One benefit of launching a startup in Albuquerque is the ability to mine well-educated graduates of UNM as employees. VisionQuest has on staff three UNM alumni in addition to Barriga. Research scientists at the firm include Jeff Wigdahl (’13 MS) and Jeremy Benson (’16 MS), who is also working toward his PhD in computer science at UNM. And Aswathy Kurup (’17 MS), who is working toward her PhD in engineering at UNM, is a research assistant.

Barriga also married a UNM graduate. He and Lauren Salm (’06 BUS, ’11 MA, ’20 MS), a speech-language pathologist, married in 2016.

Barriga never would have imagined that choosing engineering as a career would lead to discovering advances in medicine, but he is grateful for the field of research he found.

“It’s so rewarding to work in the health care field, because of the impact it has in people’s lives,” Barriga says. “It really makes you feel good about the things you’re doing. It gives you an incentive or a motivation to continue doing it.”

There are more than 450 million people around the world diagnosed with diabetes. VisionQuest hopes to bring to market an integrated set of tools that can help reduce its complications and allow patients to lead fuller and healthier lives.

“In the future you can imagine that you walk into a pharmacy and you sit down in this device where you will get your feet examined and then you put your head on a chin rest and you can get your retina pictures taken, and in one step you’ll get all of these exams done while you’re picking up your medications,” he says. “That’s the vision for a few years down the road.”